Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

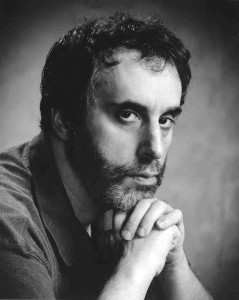

Relevant History welcomes historical military artist Don Troiani, a soul lost in time, a 21st-century artist to whom the life of the common soldier of the American Revolution through the Civil War is as familiar and vivid as the surroundings of his Connecticut studio. No other painters have turned their attention to historical art with Don’s enthusiasm, insight, and historical accuracy. He sets standards of excellence and authenticity in his field that few can equal: in his choice of models as well as his research of garb, gear, and period settings. For more information, check his web site, online gallery, and Facebook page.

Relevant History welcomes historical military artist Don Troiani, a soul lost in time, a 21st-century artist to whom the life of the common soldier of the American Revolution through the Civil War is as familiar and vivid as the surroundings of his Connecticut studio. No other painters have turned their attention to historical art with Don’s enthusiasm, insight, and historical accuracy. He sets standards of excellence and authenticity in his field that few can equal: in his choice of models as well as his research of garb, gear, and period settings. For more information, check his web site, online gallery, and Facebook page.

*****

SA: For a long time, the Northern theater of the American War of Independence received the greatest share of attention from artists as well as scholars. You’ve painted exciting scenes from four critical battles in the Southern theater: Kings Mountain, Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, and Eutaw Springs. What inspired you to explore these Southern battles as subjects for your paintings?

DT: My plan is to paint all of the major battles of the Revolution, and of course the fighting in the South is an important part of that , as the war was eventually decided there. Most previous (and some more current) renderings of these battles are inaccurate, and I hope to remedy that situation.

SA: To that end, you should benefit from the outcome of archeological projects ongoing at sites of battlegrounds in the Southern theater. In your painting of the Battle of Cowpens, you capture the ambiance of a backcountry South Carolina dawn in January. What research do you perform to depict the atmosphere of Southern battles so well?

SA: To that end, you should benefit from the outcome of archeological projects ongoing at sites of battlegrounds in the Southern theater. In your painting of the Battle of Cowpens, you capture the ambiance of a backcountry South Carolina dawn in January. What research do you perform to depict the atmosphere of Southern battles so well?

DT: I used photos taken by a friend on the Cowpens battlefield close to the date and time of the actual battle so the lighting would be correct. I always try to visit the actual location and, failing that, have someone else do it for me.

SA: How long did it take you to finish this painting of the Battle of Cowpens?

DT: Not counting research, a painting like Cowpens might take two months easel time, more or less.

SA: How many in-progress paintings do you have in your studio right now?

DT: Usually I work on one at a time, straight though. Because of the detailed historical nature of the work, it’s the only way to keep the facts fresh in my mind. If I were to stop for a month and go back to an unfinished painting, I’d have to reread all the research materials again. Occasionally, I will stop to do one of the single figure studies. There is one in-progress painting in the studio now. The next one is being posed, and the next three in are in various stages of research. There is another that’s completely researched and partly posed, but it is on a back burner, as time sensitive, commissioned work must come first.

SA: Many book authors work in a similar manner.

SA: The 33rd Regiment of Foot enjoyed a long and distinguished history that dated from about 1702. In the Southern theater of the Revolutionary War, this infantryman you’ve painted from the 33rd may have fought at the sieges of Charleston and Yorktown as well as the battles at Camden and Guilford Courthouse. How did you develop the deep level of detail for his uniform and equipment?

SA: The 33rd Regiment of Foot enjoyed a long and distinguished history that dated from about 1702. In the Southern theater of the Revolutionary War, this infantryman you’ve painted from the 33rd may have fought at the sieges of Charleston and Yorktown as well as the battles at Camden and Guilford Courthouse. How did you develop the deep level of detail for his uniform and equipment?

DT: I have been studying British uniforms for decades and collecting original items to incorporate into my painting. I consult with other experts and read original documents, returns, and inspection reports to complete an accurate picture of how these soldiers looked.

SA: Why do you occasionally use historical reenactors as models for your paintings?

DT: I rarely use reenactors dressed in their own uniforms, as most uniforms are not accurate enough for what I need to achieve, although a few are. I prefer models dressed in my uniforms and equipment here at the studio because it is easier to manage the authenticity. Reenactors do pose very well, however, as they understand the drill and firearms. I also do not take pictures of reenactors at events. Although some artists create paintings from pictures taken at reenactments, that’s exactly what you get: a painting of a reenactment. Living history is important and a lot of fun but has limited value to serious historical artwork.

SA: In my experience, the greatest contribution of living history is its hands-on element—and thus its capacity to inspire participants and spectators into learning more about history on their own after most have endured a bone-dry history class in high school.

SA: You have an extensive private collection of artifacts, such as this regimental coat worn by Lt. Colonel Benjamin Holden of Doolittle’s Minute Regiment 1774–1776. (Holden led his regiment at Bunker Hill and undoubtedly was wearing his coat during the fighting.) You use these pieces to help you develop depth in your paintings. On your web site, you state, “You can look at a picture of an artifact for days and still not know it. But examining it in your own hands reveals its texture, its substance and how it works.” What’s the most memorable insight you’ve derived from examining an artifact in your own hands?

SA: You have an extensive private collection of artifacts, such as this regimental coat worn by Lt. Colonel Benjamin Holden of Doolittle’s Minute Regiment 1774–1776. (Holden led his regiment at Bunker Hill and undoubtedly was wearing his coat during the fighting.) You use these pieces to help you develop depth in your paintings. On your web site, you state, “You can look at a picture of an artifact for days and still not know it. But examining it in your own hands reveals its texture, its substance and how it works.” What’s the most memorable insight you’ve derived from examining an artifact in your own hands?

DT: If you know something inside and out, it’s a huge advantage. There is no substitute for an intimate knowledge of the weaponry and uniforms of the era. It’s important, say, to know that a sleeve reaches to the wrist and how tight it would be to get a true period look.

*****

A big thanks to Don Troiani!

Contribute a legitimate comment on this post by Sunday 1 July at 6 p.m. ET to be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book, Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Mystery. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll publish the names of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July.

Contribute a legitimate comment on this post by Sunday 1 July at 6 p.m. ET to be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book, Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Mystery. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll publish the names of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Thanks for the terrific interview, Don. I’m pleased to have you as a guest on my blog today.

Has anyone gone the forensics route and estimated Benjamin Holden’s height and build from his coat?

Several sources I’ve read claim that the average height of men during the War of Independence was about 5’5″ or 5’6″. Does the greater average height of men nowadays affect your interpretations?

What a great interview with a stellar artist. I was intrigued by the whole idea of Don’s ambitious research in order for his art to reflect true historical battles. I visited his online gallery and was brought into the scenes of his depictions, so true to life they mesmerized me — a mark of a true historian, I think.

I sensed Don’s passion here, too, in doing something he loves. I admire anyone who is connected with living history in any form.

Welcome back, Alice! I suspect that you’re hooked.

Thanks for your observations. Speaking of true-to-life mesmerization, isn’t the range of facial expressions that Don incorporates into the characters of his battle scenes remarkable? He makes each character so much a three-dimensional individual that you can almost hear what they’re thinking — even the characters who aren’t in the center of the action. That’s what good authors do to characterize their novels, too.

We have five more days of excellent posts forthcoming. Check in each day, and enjoy!

Thanks for this interview. I’ll look forward to seeing the South Carolina related pictures as I learned while doing genealogical research as an adult that I had an ancestor who was for the colonies (and provided grain for them) whose his son, a Loyalist, fled farther South to a place so remote it is still pretty remote today.

Welcome back, Brenda! Check Don’s online gallery. He’s also painted the battles of Eutaw Springs, Guilford Courthouse, and Kings Mountain.

Suzanne, That might be the lowish average, there were also quite a few taller , however, chest sizes seem to be on the smaller sizes 34-36 etc.

Hi Don! Thanks for the supplying the intriguing statistics. That 5’5″ – 5’6″ height estimate might also represent the average height of soldiers who were born and raised in the British Isles. Studies suggests that the average height of men who were born and raised in America during that time might have been an inch or so taller — access to more resources, more space, and so forth being the influences. Is that smaller chest size associated with smaller average height proportionate to men’s average heights and chest sizes today? If so, I suspect we can chalk it up to generations of better nutrition and healthcare.

Is that smaller chest size associated with smaller average height proportionate to men’s average heights and chest sizes today? If so, I suspect we can chalk it up to generations of better nutrition and healthcare.

The smaller chest size is interesting. Many modern artists probably depict men of the late 18th century as having broader chests and shoulders than they actually had. But would people believe Continental or British soldiers that weren’t ripped?

In the British Army Grenadiers had to be at least 5’8 but there were six footers in there as well.

Made even taller in appearance by their headgear. Certain dragoons also had specific height requirements.

Fascinating blog. Please don’t enter me in the drawing. I have already read REGULATED FOR MURDER and it’s wonderful.

Thanks, Warren!

This is fascinating information from a truly talented artist (I love the realism depicted by Mr. Troiani in his works). I was somewhat surprised that the works are not derived from photos at re-enactments. I could spend a lot of time wandering thru Mr. Troiani’s gallery of Civil War works as well…thanks for sharing all his links with us, and for the informative interview.

REGULATED is wonderful, Suzanne, and I look forward to more of Lt. Stoddard–any idea when his next tale will be available?

Hi Linda! I spent far too much time wandering through just the Revolutionary War section of Don’s online gallery. The characterizations are fascinating. I want to return and check out the WW1 soldiers.

Thanks for your kind words about Regulated for Murder and Lt. Stoddard. I’m finishing up the next book right now, aiming to have it released before the end of the year.

Concerning the average height of British soldiers, peacetime recruiting standards generally called for a minimum height of 5′ 6″, and military writers suggested that this could be relaxed a bit if it looked like a man in his late teens still might grow a bit. Inspection returns, available for many regiments shortly before they left Great Britain for America, show that most British soldiers were between 5′ 6″ and 5′ 9″, with a moderate number of men taller than this and very few below 5′ 6″. The need for manpower as the war escalated led to recruiting of shorter men, but an average height within a British regiment nonetheless remained close to 5′ 8″. Whether this was a reflection of the population as a whole I cannot say.

Thanks for weighing in on this, Don. Any idea where the height statistic of 5’5″ – 5’6″ originated?

Don’t know , where did you find it?

I can only say that Don’s on line gallery just took my breath away. I am in awe of the details,expressions and even the animals in motion. I agree with the other commenter who said the paintings just pull you into the scene. I appreciate the interview and Don’s answers. I’m off to the Gallery again. Happy 4th everyone.

Happy 4th everyone.

Carol L

Lucky4750 (at) aol (dot) com