Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

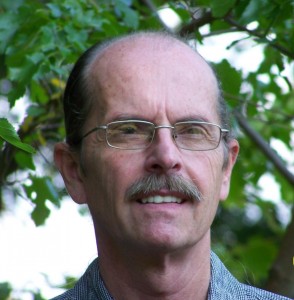

Relevant History welcomes David Neilan, editor of The Francis Marion Papers, targeted for publication in 2015. His essay below is from a longer work: “Francis Marion and Conflicts in Command in the Southern Department.” Other projects include the Hezekiah Maham orderly book, in collaboration with the NY Public Library, and the William Moultrie orderly book. He will be giving a presentation entitled “The Weems-Horry Controversy: Where Fiction Trumped History” at the Francis Marion Symposium in Manning, SC, in October. He may be reached at daveneilan1 (at) gmail (dot) com.

Relevant History welcomes David Neilan, editor of The Francis Marion Papers, targeted for publication in 2015. His essay below is from a longer work: “Francis Marion and Conflicts in Command in the Southern Department.” Other projects include the Hezekiah Maham orderly book, in collaboration with the NY Public Library, and the William Moultrie orderly book. He will be giving a presentation entitled “The Weems-Horry Controversy: Where Fiction Trumped History” at the Francis Marion Symposium in Manning, SC, in October. He may be reached at daveneilan1 (at) gmail (dot) com.

*****

Francis Marion’s activities as a militia leader in South Carolina are the foundation of his legend. The reality of the life of the Swamp Fox is much less romantic. For six months after the fall of Charlestown in May 1780, Marion operated as a guerrilla commander, virtually independent of a formal command structure. It is no wonder that when the Continental Army did rejoin the field, conflicts occurred.

Francis Marion’s activities as a militia leader in South Carolina are the foundation of his legend. The reality of the life of the Swamp Fox is much less romantic. For six months after the fall of Charlestown in May 1780, Marion operated as a guerrilla commander, virtually independent of a formal command structure. It is no wonder that when the Continental Army did rejoin the field, conflicts occurred.

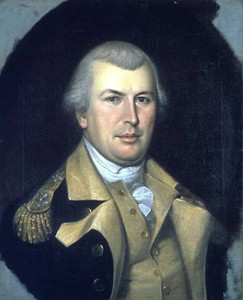

When Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene assumed leadership of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in December 1780, he had only the remnants of an army. Losses at Charlestown and Camden had decimated the ranks. Greene needed the cooperation of the militia to delay the British advance, until a sufficient Continental force arrived to re-take the state. Since authority over the militia rested with State officials, Greene recognized the need for diplomacy to put his plans into effect. His initial “orders” to Francis Marion were couched as requests, using the conciliatory “I beg you” and “Please” to obtain horses and intelligence.

When Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene assumed leadership of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in December 1780, he had only the remnants of an army. Losses at Charlestown and Camden had decimated the ranks. Greene needed the cooperation of the militia to delay the British advance, until a sufficient Continental force arrived to re-take the state. Since authority over the militia rested with State officials, Greene recognized the need for diplomacy to put his plans into effect. His initial “orders” to Francis Marion were couched as requests, using the conciliatory “I beg you” and “Please” to obtain horses and intelligence.

Marion and Greene would clash numerous times during the first half of 1781. Greene’s request for horses would be repeated numerous times. Marion’s response would express his regret, then later his irritation[1]. As the war heated up, so would Greene’s need for horses, but so would the friction between the two over Marion’s failure (Greene’s opinion) or his inability (Marion’s point of view) to supply them.

Greene continued to rely on Marion to take the action to the enemy. In January 1781 Greene dispatched Lt. Col. Henry Lee to join Gen. Marion. In his letter of 16 January, Greene was less conciliatory into his directions: “You [Marion] will give him [Lee] all the aid in your power to carry into execution all such matters as may be agreed on.”

For the next two months, correspondence between Greene and Marion was infrequent. Greene was caught up in racing to the Dan River to avoid the advance of Cornwallis and then fighting the British at Guilford Courthouse. By the middle of April, Greene and the Continental Army were back in South Carolina.

When Lee rejoined Marion, they attacked Fort Watson, a small British fort on the Santee River. During the siege, Marion received stiff criticism from his former commanding officer Gen. William Moultrie. Lee asked Greene to write “a long letr. to Gen. Marion…”[2] Greene outdid himself:

When I consider how much you have done and suffered, and under what disadvantage you have maintained your ground, I am at a loss which to admire most, your courage and fortitude, or your address and management…History affords no instance wherein an officer has kept possession of a Country under so many disadvantages as you have; surrounded on every side with a superior force…To fight the enemy bravely with a prospect of victory is nothing; but to fight with intrepidty under the constant impression of a defeat, and inspire irregular troops to do it, is a talent peculiar to yourself.[3]

Marion did not have long to savor the compliments. Greene again complained to him about his failure to furnish horses.

The 4 May “horse” letter from Greene was the last straw. An exasperated Marion fired back:

I acknowledge that you have repeatedly mention the want of Dragoon horses…if you think it best for the service to Dismount the Malitia…but am sertain we shall never git their service in future. This would not give me any uneasiness as I have sometime Determin to relinquish my command in the militia…& I wish to do it as soon as this post is Either taken or abandoned.[4]

Marion, then in the midst of the siege of Fort Motte with Lee, continued to vent to Greene:

…I assure you I am serious in my intention of relinquishing my Malitia Command…because I found Little is to be done with such men as I have, who Leave me very Often at the very point of Executing a plan…[5]

Fortunately for the American cause, General Greene was in the proximity of Fort Motte. He rode sixty-five miles to meet Marion, arriving shortly after the surrender of the fort 12 May[6].

Although Greene may have mollified Marion during this first meeting, the issues continued. During a brief lull in the fighting, Marion took the opportunity to press for orders to march on Georgetown, South Carolina:

I beg Leave to go & Reduce that place which has not more than 80 British soldiers & a few torys. The Latter is very troublesome…& by the fall of Geor Town will make them quiet.[7]

As long as Georgetown was a safe haven for the enemy, Marion would be unable to maintain his advance over the Santee River.

Marion repeated his plea on 20 May and 22 May without response from Greene. The Swamp Fox delicately announced two days later, “…I find the enemy is about evacuating Georgetown & as I cannot do any thing by remaining here I have thought it most for the service to go to Georgetown…”[8]

Greene deferred ordering an attack on Georgetown, instead advising Marion to obtain permission from Thomas Sumter, who was Marion’s superior officer in the South Carolina militia.[9]

On 28 May Marion liberated Georgetown without firing a shot.

Greene begrudgingly offered his congratulations.[10]

The relationship between Marion and Greene continued to have its ups and downs. Marion’s decisive victory at Parker’s Ferry at the end of August and then his command of the first line of militia and State troops at the Battle of Eutaw Springs in September brought him commendation from Greene.

Despite the occasional conflict over orders, horses, and command issues among subordinates, for the rest of 1781 and throughout 1782 the relationship between Marion and Greene strengthened. By the end of the war, as the two became better acquainted and the war had evolved into a containment operation, Marion was Greene’s most trusted officer.

Despite the occasional conflict over orders, horses, and command issues among subordinates, for the rest of 1781 and throughout 1782 the relationship between Marion and Greene strengthened. By the end of the war, as the two became better acquainted and the war had evolved into a containment operation, Marion was Greene’s most trusted officer.

Footnotes

1. Marion to Greene, 9 Jan 1781, ALS (MiU-C), transcription, Parks, Greene Papers.

2. Lee to Greene, 20 Apr 1781, ALS (MiU-C).

3. Greene to Marion, 24 Apr 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 144-145.

4. Marion to Greene, 6 May 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 214-216.

5. Marion to Greene, 11 May 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 242.

6. Rankin, Swamp Fox, 208.

7. Marion to Greene, 19 May 1781, ALS (MiU-C), transcription, Parks, Greene Papers.

8. Marion to Greene, 24 May 1781, Tr (ScHi, South Carolina Historical Society).

9. Marion to Greene, 24 May 1781, Tr (ScHi), There is a note on the transcript of the letter: On reverse (the outside cover of the letter) that reads, “From Genl. Marion May 24th 1781 (docketed—probably in the hand of Gen. Greene’s ADC.).”

10. Greene to Marion, 10 Jun 1781, Df (NcD).

*****

A big thanks to David Neilan. He’ll give away a DVD of the South Carolina ETV program “Chasing the Swamp Fox” to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. Delivery is available in the U.S. and Canada. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Sunday 6 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 14 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 6 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win a copy of one of my five books, the winner’s choice of title and format (trade paperback or ebook).

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Marion’s story has fascinated me since I practically wore out the American Heritage and Landmark offerings on the AWI in the south at my grade school library in the 70’s. (This being Lewis & Clark-centric Missoula, Mt. I rather quickly passed for a regional authority on the subjects! ) Working now at a professional level with military history, it’s rewarding to hear of so much detailed work being accomplished by authors who actually live in Marion country. Interesting to me is that as a nation which more than not finds itself opposing insurgents, we seem to encounter memory-blockage about a time when Americans had to become insurgents. The break in historical inheritance can be traced to an extent; certainly the Marion-Greene contretemps detailed here limited the penetration of asymmetrical warfare into what canon the Continental Army could pass on, truncated further by the resumption of command in 1812 by now-superannuated AWI veterans. Perhaps British campaigns in the Midwest and Mid -Atlantic would have suffered heavily from a dollop of Marion-style irregular warfare. The atrocity and banditry practiced by Civil War irregulars probably further soured West Point from formally examining the practice of insurgency. Had Lee decided in 1865 to take the route of the guerilla at Appomattox, Southerners might have re-lionized Marion…but in reality, 20th century US soldiers only received limited chances to fight asymmetrically during WW II Philippine occupation, and in such minute quantities as to preclude development of actual theory. Insurgency has remained an art of war Americans only study when compelled by unforgiving events. -Tate Jones, Executive Director, Rocky Mountain Museum

) Working now at a professional level with military history, it’s rewarding to hear of so much detailed work being accomplished by authors who actually live in Marion country. Interesting to me is that as a nation which more than not finds itself opposing insurgents, we seem to encounter memory-blockage about a time when Americans had to become insurgents. The break in historical inheritance can be traced to an extent; certainly the Marion-Greene contretemps detailed here limited the penetration of asymmetrical warfare into what canon the Continental Army could pass on, truncated further by the resumption of command in 1812 by now-superannuated AWI veterans. Perhaps British campaigns in the Midwest and Mid -Atlantic would have suffered heavily from a dollop of Marion-style irregular warfare. The atrocity and banditry practiced by Civil War irregulars probably further soured West Point from formally examining the practice of insurgency. Had Lee decided in 1865 to take the route of the guerilla at Appomattox, Southerners might have re-lionized Marion…but in reality, 20th century US soldiers only received limited chances to fight asymmetrically during WW II Philippine occupation, and in such minute quantities as to preclude development of actual theory. Insurgency has remained an art of war Americans only study when compelled by unforgiving events. -Tate Jones, Executive Director, Rocky Mountain Museum

Of Military History, Fort Missoula, Mt.

Tate,

An interesting sidebar to Marion’s success as a guerrilla commander is that he actively served within the regular army–first in the South Carolina 2nd Regiment and then in the Continental Army–from June 1775 until his evacuation from Charlestown in April 1780. That says a lot about one’s ability to react to changing situations.

Dear Suzanne and David,

Thank you both for sharing this facet of the American Revolution.

Like Tate Jones above, the guerilla warfare is rarely covered thoroughly, although Robert Asprey does an excellent job in War in the Shadows.

With regards to specific questions on your post:

1. You mention the conflict between Greene of the “regular” Continental army with Marion’s irregulars, but how did the prior attempt to utilize Marion and the backwoodsmen via Horatio Gates, color that relationship from Marion’s perspective? Asprey argues that Greene was much more open to Marion’s “Indian fighting tactics” than Gates had been, and as a result showed much more success.

2. I am more a student of WWII history so all the more appreciative to you, Suzanne, for your blog, books and essays on the American Revolution. However, I often see parallels with your postings and WWII—and in this case, I was reminded of Claire Chennault (Flying Tigers). This comparison is strongest with the inference that when the “regular” army comes in to a theater where a smaller group had been operating independently on limited resources and then the new commander tries to requisition those same limited resources (Chennault it was planes, Marion it was horses!) However, my question for you both deals with Marion complaining that some of his men may desert when most needed. The point is that this type of irregular warfare attracts the undisciplined adventurers who you may argue are better fighters but also very unpredictable. For Chennault the oft-cited example is Pappy Boyington. Did Marion have any infamous members or subordinates that compare?

3. In your opinions, Suzanne and David, how much of the Swamp Fox’s success(including Georgetown–“liberated without firing a shot”) was due to his reputation? Like Rommel–the Desert Fox– his legend seems to have had an effect on his contemporaries that tended to unduly panic the opposition.

Thank you both.

Best wishes,

Rory

1. Fortunately for Marion and the American cause, he made a most unfavorable impression on Gates when he appeared in the “hero of Saratoga’s” camp in July 1780. Gates sent him off to gather intelligence the day before the Battle of Camden in August. Even after the battle Gates failed to make use of Marion–only one letter from Gates to Marion is extant, while Marion wrote him at least ten times. It’s no wonder that when Greene appeared on the scene in December and ingratiated himself to Marion at the outset, Marion was receptive. Here he was, the highest ranking Continental officer still in the field in South Carolina finally being shown some respect. Marion may not have been a man whose appearance instilled respect–he was ‘old’ (for the time), had a limp, and was apparently dressed in a facsimile of a Continental lieutenant colonel’s uniform–but at heart, I feel, was of the established military order. During the summer and autumn of 1780 he had had great success in bedeviling the British, utilizing irregular tactics, but at heart I wonder if he did not continue to see himself as lieutenant commander commandant of the 2nd SC Regiment. The sieges of Fort Watson and Fort Motte show he had not forgotten how to run a conventional operation, as long as he had the manpower.

The nature of the civil war that was South Carolina added another element to Marion’s leadership challenge. He never knew how many men would be with him. A peculiarity of the guerrilla warfare in the South was that the militia man also had to maintain his farm/plantation–he had to feed his family and fight, too. When it was time to plant or harvest, Marion could expect little response to his call for militia. What was most unsettling was how his militia would operate when their general was not with them. In at least two instances, Marion mentions his regimental/corps commanders (militia colonels!!) involved in plantation burning. These were not undisciplined adventurers, but, instead, revenge seekers. He experienced other situations, where his officers went over his head or around him. It seems to me these latter cases were issues of ego, as opposed to adventure–William Clay Snipes, Hezekiah Maham, Peter Horry.

I think Marion’s reputation had a lot to do with his success. It’s clear from British correspondence that as the war progressed, Marion’s efforts were having a significant impact on the Loyalist progress. His men must have had great respect for him, given that he led them until the end of 1780 without any official commission to command the militia.

Remember that most of Marion’s Brigade had military training in their local militia units prior to the Revolution as they came from the frontier (areas more than 50 miles from Charleston).

Also, as you know from looking at Chennault and Boyington, a good way to “get dead” in combat is to be predictable … something the politicians do not seem to understand.

The militia furnished their own weapons, horses, clothing, etc., without getting paid and that alone makes a

challenge for a commander. There were similar problems presented to our commanders when we ended the draft.

Isn’t it nice to sit comfortably at a computer and consider all this instead of crawling through a swamp with

real bullets whipping past or sailing over gun and missile sites at 500 plus?

One often gets the impression that, in war, one third of the time may be spent fighting the enemy and the balance fighting colleagues. Makes Eisenhower’s success even more impressive.

Although it may seem by this brief essay that Marion was embroiled in disagreements with a number of superiors and subordinates, which he was, I do not feel his effectiveness was compromised. He did so much with so little; he came out on the short end in only one action that he led.

It was interesting, as I gathered somewhere around 600 letters to and from Marion, to learn just how many significant conflicts came his way. It was also interesting to grasp how often the responsibility for resolving the issues was passed around like a hot potato. I wrote a paper a few years ago about Marion’s conflicts in command. When I dip into it occasionally, I still marvel at the complexity of command under such relatively primitive conditions.

It always astounds me that each generation has to learn anew the lessons of non-conventional warfare. We hadn’t learned it by Viet Nam, although the Cong leader had studied Marion’s campaign, and we haven’t learned it today. You can win the big battles but you have to control the hearts and minds of the people. Clinton gave that advise to Cornwallis before he left SC, but you can see how that worked!

Boy, oh boy, Cornwallis had sure forgotten Clinton’s advice by the time he got to Hillsborough, NC in February 1781. What he did there was piss off the loyalists by inviting them to identify themselves; then he left town, so all the loyalists who had outted themselves were in the bulls eye, and Cornwallis’s regulars wasn’t there to protect them.

David, I marvel that they managed all that “complexity of command” without cell phones or the Internet. Also that more messages between those guys didn’t get intercepted.

And further complicating the fulfillment of the orders was the time lag between writing and delivery, the location of the recipient location, and the potential for the orders to be intercepted. In Marion’s case the possibility that he did not have enough men or ammunition was a real issue, as well.

David, you did a great essay and replies!

For those with interest the book, “The Swamp Fox: Lessons in Leadership from the Partisan Campaigns of Francis Marion” by Scott D. Aiken, Col., USMC, is a interesting study of Marion’s tactics compared to those used by our current forces.

It is also impressive to see Marion slide from irregular tactics to more conventional tactics during the three weeks of the Bridges Campaign from Wyboo Swamp to Sampit Bridge, 6-28 March 1781. Virtually no one covers this as they look totally at Guilford Courthouse on 15 March.

Again, well done, David! Look forward to having you and Christine Swager present at the Francis Marion Symposium.

George mentions the Bridges Campaign, a fantastic 3-week tactical masterpiece by Marion during which his militia mauled well-trained British Provincial Light Infantry. It was sandwiched between operations carried out by Marion and his militia and Henry Lee (father of Robert E. Lee) and his Continental Legion. Nathanael Greene sent Lee to assist Marion and, probably, to learn a bit about employing Marion’s irregular tactics. In a classic dawn raid–perhaps too complicated for logistical requirements–the two nearly captured Georgetown, South Carolina, in January 1781. After the Bridges Campaign and Lee’s return to the state he and Marion reverted to conventional siege warfare to capture Fort Watson and Fort Motte, effectively closing the Santee River and the Charlestown to Camden supply line. The use of the siege as a strategy to capture the forts may have been conventional, but the final tactics were anything but conventional. Watson was taken by the use of Maham’s tower, a wooden structure that hailing back to the Middle Ages, from which Marion’s sharpshooters pinned down the British in their own little fort. In the case of Fort Motte Marion employed either 1. a bow and arrow, using a fired arrow, or 2. a ball of rosin or brimstone, fired and slung on the roof of the house. The resulting fire forced the surrender of the fort. Both of these actions did much to enhance Marion’s reputation, as well as, his subsequent legend. Marion could be a little moody at times, but he was unquestionably the right man for the job.

I was a student of the late Dr. Hemry Lumpkin and he oftne mentioned marsh tackies : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carolina_Marsh_Tacky……These horses were unque to the lowcountry and also not really ideal for calvary…A fact that may have been lost on a Connecticut general. Also , you included several pictures of Marion. I think it is always immportant to note there were no pictures of of Marion pained during his life. If I remember correctly the first portrait was done by a nephew of Marion who drew, when he grew up , the face he saw as a child. Any other potrait, or picture, including the ones my friend Kate Salley Palmer did for her son’s documentary are an educated guess based on people who subscribed him.

Bill,

Point well-taken. John Blake White’s painting of Marion riding through the swamps is the only one purportedly based on actually seeing Marion.

There are a number of other portraits and paintings that are equally imaginative. The one I like the least is the depiction of Marion at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, where his right arm, holding a sword, is so contorted that one scratches one’s head trying to conceive how the artist could have thought anyone would have believed it was anyone, much less Francis Marion.

I like a contemporay artist’s–Karen MacNutt–conception of Marion, as he might have appeared in late January 1780. In a letter to Maj. Isaac Harleston Marion described the change in appearance of his regiment, including himself, presumably as a result of interacting with the French contingent at Savannah the previous October, “When you see me you will find I have a formidable pr of Mustassho, which all the regimt. now ware & if you have not one you will be Singular.”

Thank you for a great essay that provided a more in depth view and rare perspective of the effort between General Greene and Francis Marion during the southern campaign. We often forget or more likely, simply don’t know and understand all the intricacies of fighting a war in the 18th century when soldiers were at a minimum, ill-equipped, and lacking reliable and timely communications.