Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

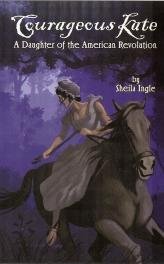

Relevant History welcomes YA author Sheila Ingle, a retired educator and teacher of writing for 37 years, and winner of the DAR Historic Preservation Award. Sheila’s interest and love for history has become a part of her new writing career. She has published articles in Sandlapper and the Greenville Magazine on the Citadel Class of ‘44 and the Frank Lloyd Wright home in Greenville, S. C. Her two biographies for young readers are based on Revolutionary War heroines of South Carolina; both Kate Barry and Martha Bratton helped the militia defeat British and Tory troops in the Upcountry in two different battles. Courageous Kate and Fearless Martha also refused to reveal information about their husbands’ whereabouts to the enemy; each faced the threats with bravery and determination. Sheila’s books are available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and Hub City Press. For more information, check her web site and blog.

Relevant History welcomes YA author Sheila Ingle, a retired educator and teacher of writing for 37 years, and winner of the DAR Historic Preservation Award. Sheila’s interest and love for history has become a part of her new writing career. She has published articles in Sandlapper and the Greenville Magazine on the Citadel Class of ‘44 and the Frank Lloyd Wright home in Greenville, S. C. Her two biographies for young readers are based on Revolutionary War heroines of South Carolina; both Kate Barry and Martha Bratton helped the militia defeat British and Tory troops in the Upcountry in two different battles. Courageous Kate and Fearless Martha also refused to reveal information about their husbands’ whereabouts to the enemy; each faced the threats with bravery and determination. Sheila’s books are available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and Hub City Press. For more information, check her web site and blog.

*****

In my book, Courageous Kate, A Daughter of the American Revolution, there is a chapter called “The Art of Housewifery.” Not all of the chores that were part of these times are described, but a good many are. In my second book, Fearless Martha, a Daughter of the American Revolution, there are more descriptions of the ways eighteenth-century women ran their homes. Mothers taught their daughters at an early age how to keep a household running smoothly. The chores were endless, and many hands were needed to make light work.

In my book, Courageous Kate, A Daughter of the American Revolution, there is a chapter called “The Art of Housewifery.” Not all of the chores that were part of these times are described, but a good many are. In my second book, Fearless Martha, a Daughter of the American Revolution, there are more descriptions of the ways eighteenth-century women ran their homes. Mothers taught their daughters at an early age how to keep a household running smoothly. The chores were endless, and many hands were needed to make light work.

The Revolutionary War women that lived on the small farms were busy from before daylight to after dark. Maybe that is where the saying “a woman’s work is never done” originated. The farmer’s wife saw to the dairy, the chickens, the vegetable and herb gardens, and cleaned house. She cured and preserved meats, made soap and candles, dried vegetables, spun thread to make cloth for clothes from her own flax, prepared meals, and doctored her family.

As I was learning about this myriad of daily tasks, I visited Middleton Gardens in Charleston, South Carolina. A large millstone was there to entertain visitors. The pole in the middle of the two stones was stout, and the stones were at least a yard wide. Turning the pole crushed the corn kernels, and this was no easy task. My whole body was involved in turning the pole; I quickly remembered the motions of the dance, the Twist, from years ago. I have to admit my practice at this didn’t last long, and my husband was kind enough not to laugh.

My grandparents owned a dairy farm in Kentucky, and I was always fascinated with the milking process, though I didn’t have a lot of personal luck. I admit I was leery of the cows after getting swatted by several of their tails at different times. There was no choice during the eighteenth century for this task, because milk was used for drinking, making butter, and cooking. Also, the cows had to be milked every day because they produced up to five gallons of milk daily. Churning is an easy, but tiring process. It sometimes took almost an hour of plunging that dasher up and down in the churn to turn that creamy milk into butter. (My husband and I have butter molds from both sides of our families that we treasure.)

When I taught kindergarten, we made candles at Christmas. It seemed an endless task for my eighteen students to walk around the table dipping their string into the hot wax. I went to Michael’s to buy the wax, but that was not available two hundred years ago. In the colonial days, the hard fat of cows or sheep was melted for the wax or perhaps beeswax was used. Bayberries were often added to give off a pleasant scent when burning, but almost a bushel of berries was needed to make just a few candles. Believe it or not, many women could make as many as 200 candles in one day. I did read that mice liked to eat candles, so the housewives had to store them carefully.

I enjoy using my crock pot to make stews or soups. The smells after several hours of cooking are an encouragement that supper is in process. In those earlier times, a large, iron pot filled with meat and vegetables would also cook all day in the fireplace. The chickens would have come from the yard, or the deer meat from a hunting expedition. The vegetables were from the kitchen garden and any herbs from the herb garden. The wife took care of scalding and plucking the feathers of the chicken. She would have prepared the ground, planted the seeds, weeded and watered the garden, and then picked her vegetables and herbs. Sometimes the family would eat on this stew for several days, with daily additions. Everything took a lot of time. Nothing was wasted. This old rhyme describes how a stew might keep on cooking. “Pease porridge hot. Pease porridge cold. Pease porridge in the pot nine days old. Some like it hot. Some like it cold. Some like it in the pot nine days old.”

John and I met Revolutionary War reenactors at Cowpens National Battlefield the other weekend, and I learned about another time-consuming task called cording. I was not familiar with this, but learned quickly that with the help of a lucet that one cord could be put together to make a stronger, square cord. These cords were used for women’s stays, drawstring bags, button loops, and anything else that needed a tie-together. A sewing basket would have cords in various stages of completion. (There are several internet sites available to find more information about this task, as well this YouTube video to help you learn this craft.) From the little bit of experience I have had with holding the yarn and the lucet, expertise making this necessity would take practice.

Speaking of the reenactors, they have learned to share this time period with us with much proficiency. They are always willing to share their knowledge and know-how of these times and the tasks that both men and women needed for survival. It is a worthwhile drive to visit any of their many campsites at Revolutionary War events, and I encourage you to do so. From the food they cook to the tents they set up, they will help open your eyes to an ordinary day in the lives of our early American families.

These are a few comparisons of housewifery between the eighteenth century and the twenty-first century; there are many others. With the well-being of their families hanging in the balance, these strong and courageous women did their jobs of taking care of both hearth and home. They left us a legacy of the importance of seeing to our households, and it is one to remember and follow their models.

*****

A big thanks to Sheila Ingle. She’ll give away a print copy of Courageous Kate to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment by Thursday 7 July at 6 p.m. ET, then post the name of the winner on my blog the week of 11 July. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Great post!

I imagine the level of work to keep a household running back then had to have varied depending on where the woman lived and the family’s level of affluence. I’m sure that a woman living in an isolated cabin in the upcountry of South or North Caroina had a lot more to do than a woman who lived Charles Town (Charleston). The woman in Charleston would have had access to shops that would have reduced her workload, the extent depending on whether her family was rich or poor. And those who were affluent had servants who reduced it even more, of course, in that the rich matron’s work was probably more of an organizing and supervisory nature, rather than doing it all herself. I know that if I had been around then, I would have preferred to have lived in a more settled area with access to whatever amenities that were available then.

The book sounds absolutely fascinating.

Suzanne, These blogs have been fantastic and I know, just for me!I am getting agreat education & introduction into so many things & I thank you & the contributors. Reading Sheila’s description of ‘housewifery’ really puts into perspective all that a woman had to do (a woman’s work indeed) and was certainly up against. I have a new appreciation for ‘colonial cooking’ and from the descriptions, vote to be a vegetarian! Looking forward to checking out this read as well. Thanks

Nice to see you here, Tracy. Exactly! In addition to all the tasks of running a household, many women produced a baby every 1-2 years and helped their husbands run businesses. By comparison, the task of soldiering almost looks easy.

Hi Helena! Thanks for returning. Our ancestors were hardy folks. It’s easy to dismiss them, their contributions, and the historical lessons they taught us. That’s a big reason why I created this Independence Day blog blitz. I’m glad you’ve enjoyed it — and there’s one more day, so make sure you come back.

Great job, as usual. Those who long for the ‘good old days’ have no idea what a busy life it was. I lived on a farm in Canada as a chld and, without electricity, we churned and lived a lot like pioneers. Cartainly cooking was labor intensive.

About milking, a task which which I am familiar. If you tie the cow’s tail to it’s back leg, you won’t get swatted. However, make sure you tie it to the leg away from you as she will keep trying to dislodge the tail and you mustn’t get kicked. Just hang on to the pail or her hoof will be in it!

And in addition to all their typical tasks, during the war, the women made things for the soldiers and their men away from home. I loved the Adams’ letters and the pleas for pins and saltpeter (for gunpowder). It’s hard to be a single parent today. How much harder it must have been to keep things running without a man to help.

Hello Tracy,

You are right that life as the mistress of a log cabin in the upcountry and a home in Charles Town would have been different. There probably would not have been quite as many hands-on tasks in the city, and servants would have helped. But the management of the household was still in the wife’s hands, as you said, and a fireplace was still the major source of light, heat, and cooking. Being able to teach and delegate would have been in each home, since a mother’s role was to pass on housewifery to her daughters. Given our options today, we are probably all grateful to be living now.

Hello Helena,

I have enjoyed researching some of the recipes of this time and have tried them out with various degrees of success. Here is one that is easy that you might enjoy, and it doesn’t involve meat. I have made them to take with me to author visits. This is a Scotch-Irish recipe brought over with the immigrants.

Shortbread Cookies

1 cup sugar

2 cups butter

3 cups flour

Blend all ingredients and bake until goden brown in moderate oven.(I used 350 degrees.)

As you can tell, these simple ingredients would usually be on hand.

Chris, I love that description of tying the cow’s tail to her leg to keep her from swatting the milker with it!

Kathy, a lot of readers are surprised to learn that after a spouse died during the Revolutionary War, there was no obligatory period of mourning before remarriage, as there was during Civil War times. The population wasn’t large enough to support such a social custom, and it just wasn’t practical.

If Chris Swager checks in with us again, maybe she can back me up or correct me on this, but I believe it was she who once told me that if a woman was traveling with her husband in Francis Marion’s army, and she lost her husband, she had three weeks to pick out another husband from among the single guys. If she failed to do so, she was no longer permitted to travel with the army.

Hello Kathy,

Your comment about being a single mom back then struck a chord with me. Besides all the myriad of tasks that the wife had, she also took over her husband’s jobs of hunting, taking care of the livestock, crops, and fences, cutting the wood for the fireplace, etc. when he was on duty as a militiaman or in the regular army. All of these were considered heavy work. The dailiness of all of it had to be daunting, and yet all I have read says they were also good neighbors. They rallied round to help bring in crops or nurse each other’s children. The sense of community was strong, and they helped each other. I honestly can’t imagine the endless days with so much to accomplish and tend to the children, too.

Sheila, your point about the “community” back in the 18th century is important. Those women absolutely could not have managed all their work without having the help of their neighbors. To a great deal, we’ve lost that sense of community. Families in suburbia easily get isolated.

Hello Chris,

Now why on earth was I not given the proper instructions on the preliminary procedures? I have a picture of my granddaddy and me ready to go milking. With my scarf on my head and sweater buttoned, I am tightly holding a small pail with both hands. I wonder if they just thought I was good for a photo shoot?

Oh wow, I’m really interested by this book. I love to see what kind of work it took to make a household run then as opposed to now. I know with a toddler, I spend a lot of time picking up after him. All the modern conveniences we have makes things a lot easier for me though.

In some ways though, I feel like I understand some of how they could have gotten things done. I wear my son in a wrap when he just has to be carried and I need to get things done. I imagine that in earlier days mom’s would have done something very similar.

Thanks for telling me about his book. I definitely want to read it!

Yes, Marion wanted no unattached women in his camp. I assume this was when he commanded the 2nd SC Regiment. I don’t think he had camp followers when he was in the swamps. I got that information from Charles Wallace, a former commander of the 2nd South reenactors, now deceased.

Thanks, Chris!

Sheila,

Holding your pail with both hands! In milking you hold the pail between your knees and use both hands on the cow’s teats to get the milk. Aren’t we glad we can buy milk by the gallon?

Chris

Hello Lisa,

They did have a multipurpose garment that they wore most of the time. It was called a modesty piece or handkerchief. Usually made of linen, it was cut in the shape of a triangle, usually about 36 inches in width. For a farmer’s wife, this was part of her daily wear. It could easily have held a baby close to her chest, allowing her hands to be free, just like the wrap you use with your son.