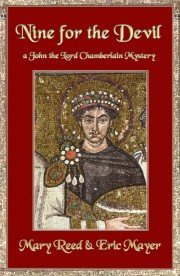

Relevant History welcomes historical mystery author Mary Reed. She and Eric Mayer contributed several stories to mystery anthologies and Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine prior to 1999’s One For Sorrow, the first novel about their protagonist John, Lord Chamberlain to Emperor Justinian I. Two For Joy, a Glyph Award winner and IPPY Best Mystery Award finalist, followed. Four For A Boy and Five For Silver (Glyph Award for Best Book Series) were Bruce Alexander History Mystery Award nominees. Nine For The Devil is the latest entry in a series Booklist Magazine named as one of its Four Best Little Known Series. For more information, check their author blogs here and here.

*****

Persecution of both Christians and pagans in the Roman Empire ended during the reign of Constantine the Great when an edict of tolerance was issued in 313. Under the Edict of Milan, freedom of worship was granted to all.

For believers of all stripes, this happy state of affairs changed under the rule of Theodosius I. In 380, an imperial edict was issued making Christianity the state religion, with adherents to other faiths declared heretics. Persecution followed.

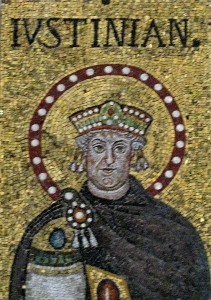

Mithraism was among the proscribed religions, and is of particular interest to me as co-author of an historical mystery series whose protagonist, Lord Chamberlain John, is a Mithran serving in the officially Christian court of Justinian I.

Mithra was a god of light. The religion had roots in Persia, and even before its prohibition, adherents worshiped in secret in underground one-room temples. Mithraism was a mystery religion with all that implies. Thus much of what we know about Mithraism comes from its enemies, who accused it of vile acts and blasphemous imitation of Christian rites.

For example, Tertullian’s Prescription Against Heretics speaks of Mithraism’s distortion of Christian rites and beliefs, stating:

…and if my memory still serves me, Mithra there, (in the kingdom of Satan) sets his marks on the foreheads of his soldiers; celebrates also the oblation of bread, and introduces an image of a resurrection, and before a sword wreathes a crown.

Tertullian’s reference to a sword and crown relates to a Mithraic rite. In Of The Crown, he elaborates further:

…any soldier of Mithra, who, when he is enrolled in the cavern, the camp, in very truth, of darkness, when the crown is offered him, (a sword being placed between him and it, as if in mimicry of martyrdom) and then fitted upon his head, is taught to put it aside from his head, meeting it with his hand, and to remove it, it may be, to his shoulder, saying that Mithra is his crown…See we the wiles of the Devil, who pretendeth to some of the ways of God for this cause…

Similarly, in the First Apology Justin Martyr writes of the Eucharist, which he says:

…the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn.

Scholasticus’ Ecclesiastical History goes so far as to accuse Mithrans of human sacrifice. In his description of the manner in which a riot broke out in Alexandria during clearance of a site formerly occupied by a mithraeum (temple to Mithra), Scholasticus states:

In the process of clearing it, an adytum of vast depth was discovered which unveiled the nature of their heathenish rites: for there were found there the skulls of many persons of all ages, who were said to have been immolated for the purpose of divination by the inspection of entrails, when the pagans performed these and such like magic arts whereby they enchanted the souls of men.

As a result of parading these skulls through the city, he goes on, fighting broke out between enraged Christians and insulted pagans.

But what was Mithraism in reality?

Mithraism was an austere religion particularly popular with soldiers, who spread it to the far corners of the empire. Although Mithraism excluded women, some of its requirements and beliefs paralleled those held by Christians.

Published in 1903, Franz Dumont’s The Mysteries of Mithra pointed out a number of these similarities. Dumont’s work is one of the most important books about Mithraism and his comments are telling.

Mithra, he said, “…is the god of help, whom one never invokes in vain, an unfailing haven, the anchor of salvation for mortals in all their trials.”

Comparing the two religions, he notes that:

The sectaries of the Persian god, like the Christians, purified themselves by baptism; received, by a species of confirmation, the power necessary to combat the spirits of evil; and expected from a Lord’s Supper salvation of body and soul. Like the latter, they also held Sunday sacred, and celebrated the birth of the Sun on the 25th of December, the same day on which Christmas has been celebrated, since the fourth century at least.

Further, both religions

…preached a categorical system of ethics, regarded asceticism as meritorious, and counted among their principal virtues abstinence and continence, renunciation and self-control. Their conceptions of the world and of the destiny of man were similar. They both admitted the existence of a Heaven inhabited by beatified ones, situate in the upper regions, and of a Hell peopled by demons, situate in the bowels of the earth. They both placed a Flood at the beginning of history; they both assigned as the source of their traditions a primitive revelation; they both, finally, believed in the immortality of the soul, in a last judgment, and in a resurrection of the dead, consequent upon a final conflagration of the universe.

It was therefore not surprising Christianity and Mithraism would struggle to gain the upper hand. As history shows, Christianity won the battle.

One reason was that because Mithraism was a mystery religion, fantastic and lurid stories of Mithran practices and beliefs found it easy to gain a foothold in, and inflame, the popular imagination.

Much of the fear of other religions comes from lack of knowledge, all too often leading to bloodshed. Consider the human toll taken over the centuries from the blood libel accusing those of the Jewish faith of murdering Christian children and using their blood for religious rituals. I was told this very story as a fact by a playmate in my childhood when my family lived in an area with a high Hassidic population.

There we see the ongoing historic relevance of religious misapprehension, with Mithraism, a religion with much to admire about it, providing another example of the dangers in reacting to, and acting upon, hazily understood religious tenets.

*****

A big thanks to Mary Reed!

*****

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Absolutely fascinating! Mary and Eric write one of my favorite series, full of interesting facts and very thought-provoking while being just plain good reading.

Welcome to my blog, Priscilla. I think Mary and Eric have niched themselves nicely, in a setting not overused by authors of historicals. It’s a pleasure to host Mary this week.

Thank you for the kind words, ladies. We write in a fascinating period with numerous colourful real life characters just crying out to be utilised — and are ever grateful it’s so!

Really fascinating, Mary…How sad that the point you make about fear of religion springing from ignorance and often leading to bloodshed still applies today. in the words of one of my favourite songs, “When will they ever learn?”