Relevant History welcomes Richard Abbott, who writes historical fiction set in the Middle East at the end of the Bronze Age, around 1200BC. His first book, In a Milk and Honeyed Land, explores events in the Egyptian province of Canaan. It follows the life, loves, and struggles of a priest in the small hill town of Kephrath. He continues to explore this world in other novels. Richard lives in London, England and works professionally in IT quality assurance. When not writing words or computer code, he enjoys spending time with family, walking, and wildlife, ideally combining all three pursuits in the English Lake District. To learn more about Richard’s books, check out his website and blog. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Richard Abbott, who writes historical fiction set in the Middle East at the end of the Bronze Age, around 1200BC. His first book, In a Milk and Honeyed Land, explores events in the Egyptian province of Canaan. It follows the life, loves, and struggles of a priest in the small hill town of Kephrath. He continues to explore this world in other novels. Richard lives in London, England and works professionally in IT quality assurance. When not writing words or computer code, he enjoys spending time with family, walking, and wildlife, ideally combining all three pursuits in the English Lake District. To learn more about Richard’s books, check out his website and blog. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

*****

“Which yet survive…”

In 1817, the poet Shelley wrote the sonnet Ozymandias, speaking of sentiments

“Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.”

Shelley was inspired by the British Museum’s acquisition of massive fragments of a statue of the pharaoh Ramesses II. His words apply to written records as much as physical ones.

Our modern alphabet is derived from Egyptian glyphs, via the indirect route of Canaanite, Phoenician, Greek and Latin. The earliest link—Egyptian to Canaanite—has only become apparent in the last decade or so, and often surprises people. As well their quite different appearance, Egyptian signs are syllable-based, typically pairs or triplets forming a sound cluster. From Canaanite through to English, we are dealing with a true alphabet. The discovery of this link has raised many profound questions.

When it was thought that Canaanite arose as a new invention around 1200BC, the appearance of written texts using alphabets about 300 years later made sense. The older, more elaborate scripts like hieroglyphic or cuneiform were thought to be barriers to literacy, with a very large set of signs, and complex links between sign and sound. Their use, it was said, ensured that writing was kept for the elite. Conversely, once alphabetic scripts appeared, literacy would boom. Enthusiastic opinions were expressed, like that of W.F. Albright: “…the 22-letter [Hebrew] alphabet could be learned in a day or two by a bright student…I do not doubt for a moment that there were many urchins in Palestine who could read and write as early as the time of the Judges.”

When it was thought that Canaanite arose as a new invention around 1200BC, the appearance of written texts using alphabets about 300 years later made sense. The older, more elaborate scripts like hieroglyphic or cuneiform were thought to be barriers to literacy, with a very large set of signs, and complex links between sign and sound. Their use, it was said, ensured that writing was kept for the elite. Conversely, once alphabetic scripts appeared, literacy would boom. Enthusiastic opinions were expressed, like that of W.F. Albright: “…the 22-letter [Hebrew] alphabet could be learned in a day or two by a bright student…I do not doubt for a moment that there were many urchins in Palestine who could read and write as early as the time of the Judges.”

This happy picture has vanished. Comparative studies worldwide have shown that high literacy rates can be enjoyed with a complex script and high sign-count such as in Mandarin Chinese. Conversely, low literacy rates exist in the presence of a simple alphabet such as Latin or Greek—or English. Real literacy means more than memorizing twenty-two symbols—twenty-six for English. It means knowing how to use these symbols flexibly, accurately, and reliably to capture information and pass it on to others. Learning how to be a writer requires more than learning your letters.

“The hand that mocked them…”

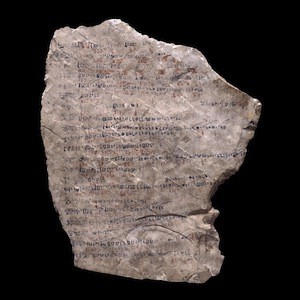

Moreover, the recognition of the link to Egypt has pushed back the appearance of the first alphabetic writing by something like half a millennium. We now look back to about 1800BC as the time when Canaanite letters became distinct from Egyptian signs. Short monumental inscriptions or assertions of ownership using alphabetic scripts appear in the later parts of the second millennium, but we do not find a lengthy text until around 840BC. If alphabets were so easy to learn and so compellingly clear, why did it take nearly a thousand years before they are employed to display national pride and propaganda?

Moreover, the recognition of the link to Egypt has pushed back the appearance of the first alphabetic writing by something like half a millennium. We now look back to about 1800BC as the time when Canaanite letters became distinct from Egyptian signs. Short monumental inscriptions or assertions of ownership using alphabetic scripts appear in the later parts of the second millennium, but we do not find a lengthy text until around 840BC. If alphabets were so easy to learn and so compellingly clear, why did it take nearly a thousand years before they are employed to display national pride and propaganda?

Of course the picture is not that simple. Some items—stone monuments, clay tablets, interior wall paintings—survive much longer than others—wax slates, wooden boards, cured leather. Perhaps the early writers in the alphabetic tradition used materials which were inherently perishable? Or perhaps some kinds of writing were reckoned to be peculiarly suited for some topics and not others? At Ugarit, on the Syrian coast, a form of alphabet existed alongside traditional Akkadian cuneiform, and each was used only in some contexts and not others. Religious epics were written in the alphabetic script, and formal diplomatic letters and records in Akkadian—but not the other way round.

“The heart that fed…”

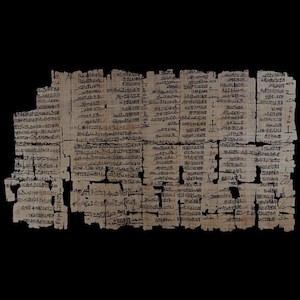

In most of the world’s history, writing has been the preserve of a few individuals, mostly men, and the topics they tackled were the concerns of the wealthy. Royal annals, battles, tribute, religious events, trade and so on fill most of the written content of the past. But sometimes we come across something more personal. The royal workmen’s village near the Valley of the Kings in Egypt was home to highly skilled craftsmen and women, and it is refreshing to read their comments about everyday concerns.

In most of the world’s history, writing has been the preserve of a few individuals, mostly men, and the topics they tackled were the concerns of the wealthy. Royal annals, battles, tribute, religious events, trade and so on fill most of the written content of the past. But sometimes we come across something more personal. The royal workmen’s village near the Valley of the Kings in Egypt was home to highly skilled craftsmen and women, and it is refreshing to read their comments about everyday concerns.

“Write to me what you will want since the boy is too muddled to say it!”…“The chief workman Paneb: Kasa his wife was in childbirth and he had three days off”…“I found the workman Mery-Sekhmey son of Menna sleeping with my wife in the fourth month of summer”…“Bring me some honey for my eyes, and also ochre that has been freshly moulded, and real black eye-paint”…“I won’t let you do singing. It is Pasen who has been assigned to do the singing for Meretseger”…“Seek out for me one tunic in exchange for the ring”…“Go and pick the vegetables, for they are now due from you.”

Many of the senders and recipients are men, but there is a good representation of women as well. The full spectrum of everyday life is captured by these letters—families, friendship and rivalry, legal proceedings, employment records, and so on. There are even shopping lists and laundry manifests. Most were inked hastily using hieratic writing on pieces of broken pottery, and passed by hand from person to person. They have a direct, intimate connection with the people of that age, and their preoccupations. But the workmen’s village is unusual, and these insights into everyday life are rare.

Writing is a strange thing. We make little marks of various shapes and use them to transmit complex and often highly personal information to other people. The story of writing continually throws new questions at us, and often challenges preconceived ideas about former generations. What we write, and how we write, tell the reader as much about the writer as about the subject matter.

And, as Shelley said, these fragments have long outlived their original personal and social context. They offer fascinating, and often perplexing, insights into the world of the past.

(The three images are publicly available from the British Museum web site.)

*****

A big thanks to Richard Abbott. He’ll give away a trade paperback copy of In a Milk and Honeyed Land to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Richard Abbott. He’ll give away a trade paperback copy of In a Milk and Honeyed Land to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Fascinating! I’m a language buff, and it’s interesting to look at the intricate relationship of writing to language.

I agree, Margaret. And who among us isn’t an armchair Indiana Jones? 😉

Agreed, Margaret, it’s great to explore all that

Richard, I just have to know…do you read Egyptian glyphs or Cuneiform?

Suzanne, I read hieroglyphs (very slowly!) and have even done some odd bits of translation, mostly of poetry. And ancient Hebrew, though I can’t speak the modern variation well enough to get around at all. For cuneiform, only a very small smattering as it wasn’t necessary for my academic work. But what I enjoyed more than the alphabets was getting to grips with the way whole pieces of writing were put together.

Do you have any idea if Swedish runes are related, however obscurely, to Egyptian glyphs? Or did they arise separately? They were pretty far away, but those ancient people got around.

Kaye, sadly I know next to nothing about Swedish runes so can’t say with confidence. My off the cuff guess would be that they arose independently, but some day it would be interesting to find out more.

I’m a written word wonk who stood in front of the Rosetta Stone staring…just staring. What a great post. I loved it!

Michele, I can imagine. I did that in front of the Magna Carta in Salisbury Cathedral.

I am hoping to get to see some of the Magna Carta celebration exhibitions here in London this year!

Michele, that room in the British Museum is one of my favourites, along with the gallery containing the remains of the tomb of Nebamun – magnificent artwork as a celebration of his life and family.

I was a huge fan of James Michener because he brought history to life. A rabbi recommended reading The Covenant to get a quick overview of that area. Maybe quick is the wedding word until you realize how many thousands of years that covers. I’m fascinated by books that take you there but don’t make you realize how they did it. Suzanne recently did that with her revolutionary war novels. I did more research and learned my 1st generation ancestor was wounded at the Battle of Cowpens as a militia member. Thanks for sharing the development of whoring. The craftsmen comments (writings) were unexpected. For surely the recipient had to be literate as well. Do you think perhaps the one was to a judge as a defense against murder in the first degree?

Diane, that Autocorrect feature is biting a lot of us in the posterior.

I agree with you on the writings from the craftsmen and workers. We’re used to thinking of them as being ignorant. Those quotes were a real eye-opener.

Typos. Typos i say. Not wedding. Should be “wrong” and i guess i misspelled “writing” or Google was having a laugh at us. … won’t repeat that one!

“Write to me what you want because the boy is too muddled to say it.” The more things change… :)!

Human nature. We cannot escape it — and that’s one of the great lessons from history.

Quite so – one of the great things about reading ancient literature is the sense of recognition of another human being, with very similar desires and disappointments, despite all the difference of years and culture.

Diane it’s alright I guessed what you meant. There are a few cases (which I didn’t quote in the post) where it is clear that the recipient would need somebody else to read out the letter to them – which of course was necessary for many people even relatively recently in the UK. But estimates of overall literacy in that workmen’s village are quoted as high as 40%, which is vastly higher than ancient Egypt as a whole, or indeed anywhere at all for a great many years. So I am sure that the recipients really could personally read many of the notes.

Great stuff. I love ancient Egypt – I wrote a mystery novel for kids set during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses III. I’ll be sharing this post with my writing friends, especially my partners on the “Mad about Middle Grade History” group blog, where we discuss historical fiction for young people.

http://madaboutmghistory.blogspot.com/

Glad that it was helpful to you, Chris. It is so encouraging to hear of writers keeping historical fiction alive for young readers – I was given a lot of pleasure as a child by reading Henry Treece, Rosemary Sutcliff and their like.

Thanks, Chris!