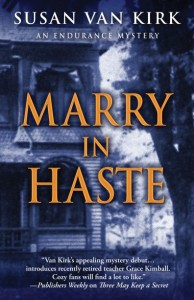

Relevant History welcomes Susan Van Kirk, who grew up in Galesburg, Illinois, and received degrees from Knox College and the University of Illinois. She taught high school English for thirty-four years, then spent an additional ten years teaching at Monmouth College. Her first Endurance mystery novel, Three May Keep a Secret, was published in 2014 by Five Star Publishing/Cengage. In April, 2016, she published an Endurance ebook novella titled The Locket: From the Casebook of TJ Sweeney. Her third Endurance novel, Death Takes No Bribes, will follow Marry in Haste. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Susan Van Kirk, who grew up in Galesburg, Illinois, and received degrees from Knox College and the University of Illinois. She taught high school English for thirty-four years, then spent an additional ten years teaching at Monmouth College. Her first Endurance mystery novel, Three May Keep a Secret, was published in 2014 by Five Star Publishing/Cengage. In April, 2016, she published an Endurance ebook novella titled The Locket: From the Casebook of TJ Sweeney. Her third Endurance novel, Death Takes No Bribes, will follow Marry in Haste. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

*****

The small town of Endurance, in the heart of the Midwest, is the setting of my mysteries. I wrote Marry in Haste, my second novel, to explore the changes in community attitudes and law enforcement regarding domestic violence/abuse. Although my book isn’t graphic about violence, I wanted to know more about this subject, especially its history and its psychological aspects. Creating two separate plots, I explored two marriages, one in 1893 and the other in the present day. Neither wife listened to Ben Franklin’s admonition to “Marry in haste, Repent at leisure.”

1893 Endurance

In 1893, seventeen-year-old Olivia Havelock travels from a farm community to her great aunt’s in Endurance, where she will learn the social graces and find a suitable husband. In that time, public sentiment favored short engagements because a long courtship might result in calling off the wedding. She quickly catches the eye of Judge Charles Lockwood, a forty-five-year-old widower, both powerful and wealthy. Four months later they are married, and then her nightmare begins. Lockwood is an abusive husband, and Oliva has little recourse from the laws, the police, and the courts.

Does history support this fictional idea? American law regarding domestic violence was founded on English law. In the time of British jurist, Sir William Blackstone [1723-1780], community attitudes and laws stated that a husband was responsible for correcting his wife’s behavior. Her words or actions, especially if they reflected poorly on her husband, could result in a beating or even murder. However, if she were to murder her abusive husband, her punishment could result in being quartered and burned alive.

By the time the Puritans arrived in the New World, they frowned on domestic abuse. However, their lack of enforcement rarely resulted in safety for their wives or children. By the late 1800s, a man was not punished for assaulting his wife. He could beat, choke, pull her hair or kick her repeatedly with impunity. Some states had a “curtain rule.” The law and courts “close” the window curtain of a home and allow spouses to solve their domestic problems. This attitude would be reflected a century later in the lax enforcement of marital abuse by police departments.

Young Olivia Lockwood has no legal help. The family doctor never asks her about her bruises; society notices, without question, her increasing absence from social events; and her servants look the other way.

2012 Endurance

In the present-day plot, Emily Folger is married to a powerful banker, Conrad, a known philanderer. When he is murdered, Emily is the chief suspect. As the story of their married life unfolds, the reader sees that they, too, are in an abusive relationship. In this era, I was more interested in exploring psychological abuse and how it often leads to post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Emily’s sister-in-law, Jessalynn Folger, tells the story of her brother Conrad’s upbringing. When his father was abusive to Conrad’s mother, Jessalynn called the police. All they did was walk Conrad’s father around the block, speak with him, joke a bit, and return him home where he was free to terrorize his wife and children. No wonder his son, Conrad, learned from a master how to abuse his wife.

Does history support this scenario? Yes, it does. Despite the Woman’s Movement in the 1960s, police officers in the 1970s were reluctant to arrest batterers. Jessalynn Folger was born in 1968, and when she saw her father hit her mother, she was a preteen in the late 70s. The prevailing community attitude was that victims chose to stay in the relationship, eliciting little public sympathy. Often abuse victims made multiple calls to police, only to grow weary of their lack of response. Police rarely arrested abusers, convincing victims that pressing charges would cause the victims more trouble. Judges issued orders of protection, and when deaths occurred, blamed police for not enforcing the law. Police blamed the courts for issuing orders that couldn’t be enforced.

Much of this changed by the mid-1980s. Women pressed for more social services for abuse and rape victims. Some disturbing legal cases where women died because police failed to respond led to a change in public and municipal attitudes. (Million-dollar law suits helped too.) By 1994, the federal Violence Against Women Act, a law repeatedly reauthorized, declared domestic violence a crime, making it more likely to be prosecuted.

In 2013, Illinois (where I live) passed a law that makes domestic violence no longer a misdemeanor. Now, if the abuser has a previous conviction, the second conviction is a felony. Four or more convictions can be given a 14-year prison sentence. Illinois is also a state, like many others, where police can now press charges against abusers if the victim is reluctant to do so.

It’s not a perfect system, but, historically, it is better. Emily Folger might have received help, but by the time her husband had isolated her, torn down her self-confidence, and bullied her repeatedly, she was suffering from PTSD, unable to think straight. While laws today are better, sometimes victims are not able to use them.

Exploring domestic abuse through history for Marry in Haste has been an interesting research expedition into an area of human behavior that I now understand much better, and I hope readers will also learn more about the psychological components of this subject, now considered a legal crime.

*****

A big thanks to Susan Van Kirk. She’ll give away a hardcover copy of Marry in Haste to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Susan Van Kirk. She’ll give away a hardcover copy of Marry in Haste to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

This topic is so huge that no guest essay could do it justice within the space limitations of a single Relevant History post. So I’ll play Devil’s Advocate and note that battered women didn’t always receive no justice from the courts.

Only recently has the institution of marriage eroded in social importance. Centuries ago, marriage was so important that if a judge turned a blind eye on a battered wife, it could incur a form of vigilante justice from men in the town. A group of them would abduct the abusive husband and beat the tar out of him. If he survived (and sometimes he didn’t), one such experience was usually enough warning for him to halt the physical battering. As this “rough music” encouraged many abusive husbands to become more creative with their psychological battering, and it essentially provided violence to combat violence, it wasn’t a good solution.

Also, judges DID grant battered women divorces. If the husband had committed adultery, or if there were several witnesses to the battering, an abused wife usually got the law on her side. However there were no quickie divorces. She often had to wait several years to receive a divorce. And of course some men continued their abuse on their ex-wives.

You are so right about how huge a topic this is. My sources were recent books written by people in the field of domestic abuse: “Stopping the Violence” by the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence,; the Journal of Comparative Family Studies; Susan Schechter, Barnett and LaViolette ” It Could Happen to Anyone: Why Battered Women Stay”. These are only a few of the 30+ sources I used as research on this topic.

My comment was meant to show how truly huge this issue is by contesting two prevalent myths that 21st-century people have about domestic violence.

Myth #1: Battered women throughout history have never had legal recourse. Historically the legal system hasn’t been too effective at helping battered women. A battered wife could attempt to get a divorce, but if it was granted, she’d have been waiting on it a long time. Women sometimes physically separated from their abusive husbands. When they did so, they had help, which leads into my next point.

Myth #2: All men approved of wife beating. History is full of decent men who never hurt their wives. And the people who helped a battered woman leave her husband were often her horrified male relatives.

We aren’t going to be effective at combating and stopping this issue until we (a) acknowledge where we’ve come from historically, with accuracy, and (b) identify who stands to gain by perpetuating myths like these.

As a Women’s Studies major, I have always found this area of history — and the present day — gut wrenching. Looking forward to Susan’s new book.

(I’m in Canada, so don’t enter me in the draw).

Thanks for dropping in. I remember you and yes, I agree with the “gut wrenching.” It is such a complex topic, and so much psychology goes into the relationship. Fortunately, by now we have a pretty good idea of how abusers act, so it is easier to explain that to victims who, of course, feel it is all their fault.

Thank you for sharing this Suzanne. Saw your post on FB, American Historical Fiction Fans group.

I am beginning to write my first novel, set in 1892, between the textile mills in New Hampshire and Chicago, close to the World’s Fair (where I have never been, having grown up in Massachusetts, so lots of research).

My plot does not include domestic violence in the same way, rather a woman who’s husband wants to commit her to an asylum because his bank is failing and he can’t deal with her opinionated and outspoken ways. (That is greatly simplifying the plot.)

My research on the 1800s shows that husbands could have their wives committed to an asylum for most any reason and that choice was often made when the husband wanted a divorce.

What Susan points out about law enforcement attitudes in the 1970s, I also had experience with that. My parents separated due to my father’s alcoholism and would frequently try to get in the house when he was really drunk. The first time I called the police (I was 17) they took their time coming when they heard it was domestic. So the second time I called weeks later, I told them someone was trying to break into the house and they came much faster. We were fortunate that there was no real danger, though the attitude.

Thank you both for this article. Yes, it is a huge topic and I am hopeful that we will reach and touch many by the historical fiction vehicle and empower those who still feel trapped to see a different way out.

Thank you, Pam. Strangely enough, the World’s Fair (Columbian Exhibition) is the honeymoon destination of one of my married couples. So I, too, needed to research that. It is fascinating.

At one point in the 1960s, I was working at a mental hospital. Even then, people were able to have someone committed without much hassle. Sometimes, parents committed their sons so they would have a record of being committed and would not have to go to Viet Nam. Lots of abuses back then.

You were very bright to come up with a way to get around the problems of the 1970s. The real problem is victims who do not want to testify because they are too afraid and have no resources. Now that more states are letting police press charges, the situation is better. However, they still need someone to testify. So many Catch-22s in this whole situation! Thank you for stopping by.

Pam, when I did a citizens’ police academy course, I asked cops why they hate domestic calls. They said those are some of the most dangerous calls they go on. Someone usually has a weapon. Also alcohol and drugs usually play a role.

When I was newly graduated from college, in my first job and living in an apartment by myself, I called 911 one night when a neighbor woke me and several other neighbors, hollering for help because she was being beaten by her husband. The husband had a knife and was drunk, and it took three cops to subdue him. They hauled him off to the slammer, and I never saw his sorry arse again. I caught up with the woman a few days later and asked her how she was doing. She’d filed for divorce, and she told me with tears in her eyes that the cops said three people from the apartment complex had called 911 to report the incident. The tears in her eyes were gratitude. Her husband had beaten her several times before, in other apartments where they’d lived, and she’d screamed for help, but NOBODY had ever called 911. That’s really sad.

Thank you, Susan and Suzanne, for shedding light on this important subject. Progress has certainly been made on handling domestic physical abuse. Getting help for psychological abuse isn’t as straightforward as a call to the police. But counselors and, hopefully, friends and family can help victims of the kind of abuse that leaves only internal bruises. –Maya Corrigan

Excellent point, Maya. Fortunately, the Violence Against Women act has provided more money for shelters and psychological help. But it isn’t enough. The current-day victim in my story has more family help, and that makes a huge difference. But so many times, families don’t understand why a victim stays with an abuser. Thank you for posting this great response.

When I lived in Atlanta, I did some volunteer work in a shelter for solo women and women with their children. A note was taped above the wall telephone. It said, “Don’t tell anyone that Janie Smith is here. Her husband is DANGEROUS.” Even today, 20 years later, that still boggles my mind. The woman had no home, and a loony man was hunting for her.

September 2012, a divorced mother from Alabama was gunned down by her ex-husband within walking distance of my home. She’d received custody of their three school-aged children and come to Raleigh with them in attempt to start over. The ex-husband killed himself, orphaning the children. Sad, sad, sad.

Thank you. I’ve researched the subject. Interested in this fictional interpretation.

Thanks, Julia. I hope you like it.

What a heartrending topic to explore, Susan! I’m wondering if your research provided any insights into how the victims themselves reacted to the abuse. Were they worried that any attempt to help them might only make the situation worse? Did they somehow rationalize what was going on, perhaps blame themselves, even? The police are more willing to step in these days, but despite the progress we’ve made getting someone out of an abusive situation is no simple matter.

Yes, it did provide insights. Many of the books I read were written in groups of women, some in prison for killing their abuser, some recoved and wanting to talk about it. They suffer, often, from PTSD. Their abuser tears down their self-confidence, isolates them, and makes sure they have no source of financial help (like a job.) They never know who is coming in the door in the evening: their husband/partner who is fine, or their husband/partner who is angry. The smallest thing a victim does can set off an abuser. Their abuser makes sure they blame themselves. Women who leave have a very high possibility of being killed. A victim really needs outside help: a shelter, family, psychologist. Even orders of protection often result in a victim being battered or killed. It is a very difficult topic!But I wanted to know more about it, and my book is a start.

I hope your book raises greater awareness on this issue, Susan. Thank you for having the courage to confront it. Researching a topic like this can’t have been easy.

Thanks, Nupur.

Susan

Thanks for bringing the trauma of domestic violence to readers’ attention. Many people don’t understand how serious the problem was and is. Husbands’ physical and economic control over women’s was part of the women’s movement in the 19th century. Getting the vote didn’t solve the problem. I fear the situation isn’t a lot better than it was in 1994. I’ve heard police officers talk about they return again and again to the same households. The financial and psychological support systems fail many abused women. The police also talk about how violence constitutes a problem in teenage dating. Bad patterns—misogyny, racism, etc.—pass down from generation to generation if we don’t find a way to disrupt them.

And because the abusive husband often has greater access to finances, he can hire a better attorney. In the courts, it seldom matters who’s wrong or right. What matters is how well your attorney dances.

Suzanne, you are so right. Court cases I explored showed just that. Courts are getting a little better at letting PTSD experts testify, but not always. So if a woman has few resources, she is stuck.

Carolyn, you are so right.I spoke with someone the other day, (I know, anecdotal), who had police come, and the police said exactly that. They spent their entire day dealing with abuse situations in households. And for police, this is often a very scary call to get. I use the generation to generation idea in my book, for it is quite true. I don’t know what the answer is. For now, it is a case-by-case situation. Some victims survive and leave with help, some are murdered, and some go back.It is a power issue and an economic issue.

Abraham Lincoln had a 70-year-old woman, Melissa Goings, for a client because when defending herself from her abusive husband she hit him with a piece of firewood and he died.

While speaking with her before the trial she asked where she could get a drink of water. Lincoln replied that there was mighty good water in Tennessee. She disappeared from custody and was never seen again in Illinois.

Honest Abe.

What a great story, Warren!

Thanks for this post! Not enough attention is paid to domestic violence despite the fact that it is so widespread. It cuts across social class, age, ethnicity, religion. It’s incredibly pervasive in all societies yet we don’t talk about it because of the shame factor. This post shows how far we’ve come, and yet we have a long way to go. I used my own experience as the inspiration for my YA novel “Girl on the Brink,” which chronicles a teen abusive relationship and how the protagonist gets herself out of it. If it helps just one girl, I will feel I’ve done my job. I’m sure you feel the same.

That’s wonderful, Christina. Teenage and college abusive relationships are yet another phase of all this. If you have never been in such a situation, it’s hard to understand.

I read and reviewed in Le Coeur de l’Artiste this month. Good to see domestic abuse handled so well and woven into the mystery genre. Congratulations, Susan, on a good read.

Gosh, thanks a lot for your kind words.

Abusers often threaten, or do actual harm to the women’s children and/or pets as a way to control her. If she is scared for herself, she’ll be that much more terrified of the harm to other innocent lives, which abusers very often get even more sick delight out of. When women can’t get enough help to cover all the needs of the ones they love and want to protect, it creates the kind of situation where she will stay and try her best to appease the abuser, suffering even longer. While I know that vigilante justice is not the best way of dealing with violence, I do understand wanting to deal with a ‘cancer’ by just excising it from a victim’s life.

You explain well why women stay, and why this is so difficult. In my book, I did not deal with the children because traditional/cozy mysteries usually do no harm children or animals. There is the suggestion, however, that the children probably saw and heard some terrible things. They are also not at home when their father is murdered. But in real life you are right. Protecting loved ones and pets figures into the mix.

This is a wonderful and informative post, Susan and Suzanne. I hung onto every word. The subject of domestic violence is very much current as noted in the news I read just about every day. But as I read about the Endurance series here, I am intrigued by the paralleling stories. However, events from my own childhood intruded on this read and I couldn’t help think about when I grew up in the 50s, with an alcoholic father who wouldn’t harm a fly and a mother who was both a physical and verbal abuser. I probably have PTSD from the experiences of remembering her locking the door on my father and him knocking the door down to get inside the house and injuring himself many times. To my knowledge my father never raised a violent hand to anyone even though I remember other events, as well. As time has gone by, I realize that my mother’s actions could possibly be associated with her upbringing and possibly how her mother behaved toward her. Though my experiences are “opposite” of the subject of this post, I related to the PTSD part in a different way…

Since I wrote this book and people have started reading ARCs, I have heard so many stories about how widespread abuse is. And, as you suggest, it comes in all kinds of configurations. I made the wives victims because statistics show that is more likely. Thank you for reminding us that men suffer too.

Really interesting article on this subject. Glad to know there is help out there for these people.

Thanks for stopping in, Joye. Yes, help is out there, but not everywhere.

And many people are afraid to ask the police for help, particularly if they’ve seen how useless restraining orders can be.