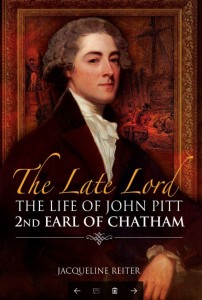

Relevant History welcomes Jacqueline Reiter, who has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017. For more information about her and her books, visit her blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes Jacqueline Reiter, who has a PhD in late 18th-century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017. For more information about her and her books, visit her blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

A concern for efficiency

During the Napoleonic Wars, concern that British government departments were riddled with corruption gave rise to a series of political commissions investigating the way those departments were run. The British Army was growing rapidly in size, and anxiety over the rise in military expenditure led to the establishment of the Commissioners of Military Inquiry in 1805. In February 1810, they published their Twelfth Report.

At first, the report did not cause much excitement. The government, headed by prime minister Spencer Perceval, was distracted by more pressing things. The House of Commons was inquiring into the failure of the previous year’s Walcheren expedition. The expedition had not even come close to achieving its objectives, and more than a quarter of the 40,000 participating troops had come down with ‘Walcheren fever’ (mostly malaria, combined with typhoid and dysentery). The expedition’s commander, Lord Chatham, was a member of the cabinet as Master-General of the Ordnance. The day the 12th Report of the Commissioners of Military Inquiry was released (27 February), Chatham appeared before the Walcheren inquiry a second time to be grilled on his role in the disaster.

At first, the report did not cause much excitement. The government, headed by prime minister Spencer Perceval, was distracted by more pressing things. The House of Commons was inquiring into the failure of the previous year’s Walcheren expedition. The expedition had not even come close to achieving its objectives, and more than a quarter of the 40,000 participating troops had come down with ‘Walcheren fever’ (mostly malaria, combined with typhoid and dysentery). The expedition’s commander, Lord Chatham, was a member of the cabinet as Master-General of the Ordnance. The day the 12th Report of the Commissioners of Military Inquiry was released (27 February), Chatham appeared before the Walcheren inquiry a second time to be grilled on his role in the disaster.

It took some weeks, therefore, for anyone to notice that the 12th Report contained political dynamite.

‘An omission of duty’

The report drew attention to some serious irregularities in the behaviour of the Treasurer of the Ordnance, Joseph Hunt. The position of Treasurer was one of great trust, since the Ordnance had enormous public funds at its disposal, funds which were meant to be devoted to the department’s vital task of keeping the army and navy stocked with muskets, cannons and gunpowder.

(Image: Ordnance shield, Wikimedia Commons) The Commissioners discovered that Hunt had been making money from the interest on the Ordnance funds in the Bank of England. Worse, he had been withdrawing drafts of money made out to recognised Ordnance suppliers and stealing the cash.[1] As a result, Hunt had managed to cream off a total of £93,296.

(Image: Ordnance shield, Wikimedia Commons) The Commissioners discovered that Hunt had been making money from the interest on the Ordnance funds in the Bank of England. Worse, he had been withdrawing drafts of money made out to recognised Ordnance suppliers and stealing the cash.[1] As a result, Hunt had managed to cream off a total of £93,296.

It appeared to be an open-shut case. Hunt resigned and promptly disappeared, popping up a few weeks later in Lisbon, where he had apparently been forced to make an unexpected journey for the benefit of his health.[2] Less than a fortnight after the end of the Walcheren inquiry, oppositionist John Calcraft moved a direct censure on Chatham and the Board under his command.

The censure was nevertheless thrown out by 54 votes to 36. Hunt was expelled from the Commons, in which he had a seat as an MP, and the £100,000 deficiency was made good from a surplus elsewhere.

A damp squib…

Surprisingly, nothing more was done. The opposition had apparently missed a sterling chance to strike a blow against government corruption. Yet nobody questioned whether or not the Master-General of the Ordnance was personally implicated in Hunt’s embezzlement. Calcraft specifically ruled it out: ‘He did not mean to impute the slightest blame to Lord Chatham, who, he believed, knew nothing whatever of the transaction.’[3]

Partly this may have been because there was no value in flogging a dead horse. Chatham, by April 1810, had been out of office a month: the Walcheren inquiry destroyed his public career and forced his resignation from the Ordnance. Attacking him directly could do little damage.

Partly, also, the opposition had probably been distracted by the Walcheren inquiry since the beginning of the year, and had little energy left for an Ordnance assault. Opposition member George Tierney, for example, thought the Walcheren inquiry had made the Commons reluctant to launch potentially involving inquiries into other things.[4]

…and a historical mystery

How far was Chatham involved in Hunt’s activities? He and Hunt were old connections, and Chatham had made Hunt his private secretary when he had been First Lord of the Admiralty in the 1790s, elevated him to the post of Commissioner of Victualling, and made him a Director of Greenwich Hospital.[5] On the other hand, the structure of the Board of Ordnance (the duties of the Board and the Master-General’s activities did not always overlap) might have protected Chatham from knowing what his Treasurer was doing.

(Image: John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, studio of John Hoppner, 1799, courtesy of the Commando Forces Officers’ Mess, Royal Marines Barracks, Plymouth) Chatham, of course, denied involvement. ‘I am extremely shocked at ye Report about Hunt,’ he wrote when the report first became public, ‘but I am not yet apprized to what extent it [the defalcation] goes.’[6] Perceval took Chatham’s protestations of innocence at face value, but others were unconvinced. ‘Mr Hunt declared…that not a shilling had ever been taken by him on his own acc[oun]t – from whence it is imagined that L[or]d Chatham is not free from the matter,’ one political commentator gossiped.[7] To many, it seemed impossible that the Master-General of the Ordnance should be ignorant of the activities of his own Treasurer.

(Image: John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, studio of John Hoppner, 1799, courtesy of the Commando Forces Officers’ Mess, Royal Marines Barracks, Plymouth) Chatham, of course, denied involvement. ‘I am extremely shocked at ye Report about Hunt,’ he wrote when the report first became public, ‘but I am not yet apprized to what extent it [the defalcation] goes.’[6] Perceval took Chatham’s protestations of innocence at face value, but others were unconvinced. ‘Mr Hunt declared…that not a shilling had ever been taken by him on his own acc[oun]t – from whence it is imagined that L[or]d Chatham is not free from the matter,’ one political commentator gossiped.[7] To many, it seemed impossible that the Master-General of the Ordnance should be ignorant of the activities of his own Treasurer.

The truth will never be known, and there is no evidence to link Chatham to Hunt’s activities. The opposition’s reluctance to involve him in the investigation suggests they had no evidence either. It is highly unlikely that Chatham was implicated in Hunt’s activities, but even if he was innocent, it was probably lucky for him in the long run that Walcheren focused so much away from the Board of Ordnance.

References

[1] Gareth Cole, Arming the Royal Navy, 1793-1815 (Routledge, 2012), p. 28.

[2] Parliamentary Debates XVI, pp. 733-4.

[3] Parliamentary Debates XVI, pp. 637-8.

[4] Lord Boringdon to Lady Morley, 7 February 1810, British Library Add MSS 48227 f. 200.

[5] Morning Chronicle, 30 January 1810; St James’s Chronicle, 3 April 1790.

[6] Chatham to Spencer Perceval, 23 January 1810, Cambridge University Add.8713/VII/B/9.

[7] Lord Boringdon to Lady Morley, 27 January [1810], British Library Add MSS 48227 f. 175.

*****

A big thanks to Jacqueline Reiter.

A big thanks to Jacqueline Reiter.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

What happened to Hunt?

Interesting titbit of history.

I admit I don’t know. According to his entry in the History of Parliament, he died in 1816 in France — although this may or may not have been a front to escape public scrutiny!

I love it! A blog post with footnotes. What fun. Not to mention how folks complain about corruption these days.

Glad you enjoyed it. And no, political corruption is definitely not a modern invention!

And no, political corruption is definitely not a modern invention!