Relevant History welcomes back Michael Cecere, who was raised in Maine but moved to Virginia in 1990 where he discovered a passion for American History. Mr. Cecere has taught U.S. History for nearly three decades and is an avid Revolutionary War reenactor and writer who lectures throughout the country on the American Revolution. He is the author of thirteen books on the American Revolution and nearly as many articles. His books focus primarily on the role that Virginians played in the Revolution.

Relevant History welcomes back Michael Cecere, who was raised in Maine but moved to Virginia in 1990 where he discovered a passion for American History. Mr. Cecere has taught U.S. History for nearly three decades and is an avid Revolutionary War reenactor and writer who lectures throughout the country on the American Revolution. He is the author of thirteen books on the American Revolution and nearly as many articles. His books focus primarily on the role that Virginians played in the Revolution.

*****

Lexington and Concord, Trenton, Saratoga, and Yorktown—these are the Revolutionary War battles that are taught in every school district in America and that many Americans are familiar with. These key events, all of which happen to be American victories in our struggle of independence, spanned six years and contribute to the mistaken impression held by many that American success in the Revolutionary War was inevitable.

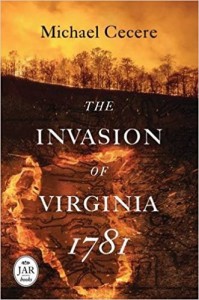

What is overlooked by many are the numerous American defeats and setbacks that occurred in between these important victories: the suffering and struggles and yes, numerous losses that Americans fighting for their rights and independence endured between 1775 and 1783. My latest book, Invasion of Virginia, 1781, sheds a long overdue light upon one crucial military campaign in Virginia that occurred prior to Yorktown and that significantly contributed to what became the decisive battle of the Revolutionary War, the siege of Yorktown. To put it bluntly, we do not get to Yorktown without experiencing the Virginia Campaign of 1781.

Defeat and treason

The situation looked quite bleak for supporters of American independence in late 1780. The British had successfully gained control of most of Georgia and South Carolina (destroying two American armies sent to resist them at Charlestown and Camden) and the British commander in the South, General Lord Charles Cornwallis, had turned his attention to North Carolina. To the north, General Washington and his army was stunned by the betrayal of General Benedict Arnold, the hero of Saratoga and one of Washington’s best generals. Disappointed by insufficient French support, which left Washington too weak to strike the British in New York, and fearful that others in his army might follow Benedict Arnold’s example, the American commander and likely most supporters of independence were anxious for what lay ahead.

The British commander in America, General Henry Clinton, was pleased by the success of his new southern strategy, and sent a force under General Alexander Leslie to Virginia in October to assist General Cornwallis in his subjugation of North Carolina. The surprising defeat of a large force of Tories at King’s Mountain undermined Cornwallis’s plans for North Carolina and caused him to order Leslie southward to South Carolina.

General Clinton was not pleased by this development; he believed that control of the Chesapeake Bay was crucial for gaining control of the south, so in December he sent a new British force of 1,600 men under Brigadier-General Benedict Arnold to Virginia with orders to establish a secure post in Portsmouth and destroy and disrupt whatever military supplies that he could that were destined for the American southern army in North Carolina.

British attention turns to Virginia

Arnold’s expedition to Virginia in early 1781 was enormously successful for the British. Arnold quickly secured Portsmouth and sailed up the James River against virtually no resistance from the largest of the thirteen American states. War fatigue and mismanagement suppressed Virginia’s ability to confront Arnold, and his troops plundered their way past Richmond, destroying vast amounts of military and civilian supplies.

Arnold returned to Portsmouth before January ended and for a time it looked like he had placed his force in extreme danger for Virginia’s militia forces gathered, and then a French naval force arrived, but they were soon chased away by the arrival in March of General William Phillips with 2,500 reinforcements. General Clinton was determined to sever Virginia’s lifeline to the Carolinas, and General Phillips was to see this done. He led a strong force back up the James River, where he confronted Virginia militia near Williamsburg and in Petersburg, but his effort to occupy Richmond was thwarted by the arrival of General LaFayette with nearly 1,000 American continentals, the cream of General Washington’s army (picked light infantry).

Unfortunately for General LaFayette, the arrival of General Cornwallis in Virginia in May (following his pyrrhic victory at Guilford Courthouse) and new British and German reinforcements from New York increased the number of British troops in Virginia at over 7,000, far more than LaFayette’s small force could handle. What ensued was several days of a cat and mouse chase; Cornwallis pursed LaFayette, but not very aggressively, while LaFayette grudgingly fled northward towards overdue reinforcements under General Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania.

In early June Cornwallis broke off his pursuit and sent detachments to raid a supply depot at Point of Fork and the Virginia Legislature (which had fled to Charlottesville). The timely warning of Jack Jouett spared more of the assembly, as well as Governor Jefferson, from capture, but the raid demonstrated that British troops were capable of appearing almost anywhere in the Old Dominion.

By mid-June General Cornwallis was marching east, back towards Williamsburg. Along the way his rear guard skirmished a detachment of LaFayette’s troops who had raced all night to catch the British rear guard, near Spencer’s Ordinary. Two weeks later, it was Cornwallis’s turn to catch LaFayette off guard by luring him into a trap at Green Spring near Jamestown. Fortunately for the Americans, they were able to withdraw before they were completely trapped, but the fight was intense and costly.

Cornwallis’s return to Portsmouth in July and subsequent decision to occupy Yorktown (in compliance with General Clinton’s orders to establish a winter port for the British navy) provided an opportunity that General Washington seized upon in August when he learned that a large French naval force intended to sail to the Chesapeake Bay. General Washington’s concentration of forces outside of Yorktown was a tremendous logistical achievement and the allied victory over Cornwallis in mid-October the decisive battle of the Revolutionary War.

It is likely though, that none of it would have occurred had not events transpired in Virginia in 1781 the way they did.

*****

A big thanks to Michael Cecere.

A big thanks to Michael Cecere.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Isn’t it amazing how little we know of our history? It seems even less is taught in schools now. I learned a bit about the War of 1812 through buying local history books when we sailed on the Chesapeake Bay and stopped at various places. I’ve referenced a bit of it in my Chesapeake Bay mysteries.

Thanks for stopping by, Norma. Yes, so little is taught in school that it’s like we have to visit actual historical sites to get the history.

This is especially true Norma about our own local history. I’ve been fortunate to live in one of the most historic states in the country, Virginia, and I am astonished that so few people are aware of the history that occurred in their backyards, much less their country. As a public school teacher myself, I’m sorry to say that what we teach is largely determined by a handful of state and local bureaucrats who get to set the curriculum and write the standardized tests. They tend to favor a bland, nationalized form of history that barely scratches the surface of any particular era.

Would be most interested if Mike’s work touches upon the historiography of the Southern Campaign. The D.A.R. was founded in large part to reconcile Northern and Southern women after Reconstruction through the vehicle of Revolutionary -period commemoration, and it seems the Southern Campaign would have met that end nicely. While “Lost Cause” worship clearly took up most of the internal

historic oxygen in the Southern sphere, would like to see if Rev. War. remembrance (antecedents in the 1876 Centennial, or recent wounds too raw?) in the South took on new significance among former Comfederate adherents or was mainly a public screen to divert Northern attention from post CW issues of race relations and national loyalty…

Tate Jones

Executive Director

Rocky Mountain Museum of Military History

Fort Missoula, Mt.

Tate, thank you for your comment. I’ll make sure that Mike sees it. He’s in the process of moving.

Hello Tate,

I’m afraid my knowledge of the historiography of the American Revolution is inadequate to address your question. This is a double edged sword for though I remain largely ignorant of the “agendas” of past writers, my limited use of such potentially biased sources (in favor of primary sources — which admittedly can also be biased for other reasons ) reduces the chance that I have been influenced, either subtly or overtly, to adopt their views or advance their agenda.