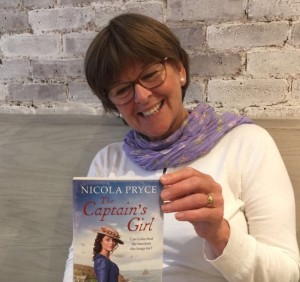

Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Nicola Pryce, who trained as a nurse in St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Her interest in literature and history saw her completing an Open University degree in humanities, and while her children were young she qualified as a library assistant to work in school libraries. Her love of Cornwall, her fascination with the Enlightenment, and her increasing desire to write saw her leave nursing to begin her novels. Pengelly’s Daughter was published in 2016 and The Captain’s Girl in July 2017. The Cornish Dressmaker will follow in 2018. Nicola lives in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Nicola Pryce, who trained as a nurse in St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Her interest in literature and history saw her completing an Open University degree in humanities, and while her children were young she qualified as a library assistant to work in school libraries. Her love of Cornwall, her fascination with the Enlightenment, and her increasing desire to write saw her leave nursing to begin her novels. Pengelly’s Daughter was published in 2016 and The Captain’s Girl in July 2017. The Cornish Dressmaker will follow in 2018. Nicola lives in the Blackdown Hills in Somerset. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and Pinterest.

*****

Cornwall 1793: Britain is at war with France

I was in the Cornwall Record Office in Truro, holding my magnifying glass against the tightly written letters. The voices leaping from the fading ink were urgent:

I was in the Cornwall Record Office in Truro, holding my magnifying glass against the tightly written letters. The voices leaping from the fading ink were urgent:

Consider, I beseech you, what inestimable interests are exposed when your country is at stake: not merely your persons and property, but your dearest relatives and friends, the wives of your bosoms, and the girls of your heart.

I thought of this morning’s news and felt a rise in my heartbeat:

They are coming against us…not for glory, territory, or dominion, but for the very sinews, the bones, the marrow, the very HEART’S BLOOD of Great Britain.

The words jumped out at me. …to glut their lust with our wives and daughters… I could feel their dread. Every document shouted their fear. Your aged parents and your tender offspring—the fruits of your labour, and the means of your subsistence.

Reading their voices was enough to make my heart beat faster. But what if I couldn’t read? What if I was huddled in a frightened group listening from the pulpit, or in the market square? They were coming against us …to punish us for outrages. The south coast of Cornwall was but a twelve hour sail from France. They could invade any moment.

Those who read the letters or heard the town crier must have been terrified, nodding in agreement at the wise words of their betters. Attend, therefore, with alacrity to the calls of your Government.

The calls of your government

Imagine looking along the cliff tops at the woeful state of the defences, the tumbled-down batteries and crumbling fortifications, knowing that the Militia of Cornwall was deployed elsewhere? Britain was defending her shores on two fronts, the Irish Papists were proving sympathetic to the French, and local Militia were thought to be more effective away from their home towns. Imagine realizing there was nothing between you and the immediate invasion of brutal French Revolutionaries?

I read the signature on another letter. It was dated 1798, from Henry Dundas, Secretary for War in William Pitt’s Government. His writing was neat, urging the Lord Lieutenant of the County of Cornwall to do everything in his power to man the batteries …that the allowance for cloathing and one shiling per week will be given to every man residing in the neighbourhood of a battery.

His call was heard. Across Cornwall, companies of volunteers were being mustered. Hundreds of men came forward to learn how to march and drill, how to fire muskets and cannons. Redoubts were dug, the newly fortified batteries manned. A watch was set and secret signals put in place:

In case Captain Bray should come under the Gribbon with his cutter you are to know him by the following signal. By day he will show the customs house colours. By night he will show a couple of lights abreast each other.

The French called a Levée en Masse, placing every citizen at the disposal of the French war machine. I spread out the closely written papers, document after document outlining the need to be vigilant and prepare for invasion. Every man, woman, and child (even un-christened infants), all livestock, all barns, carts and boats …to be recorded on a list of returns and sent up the chain of command for the Secretary of State to lay before the King.

A Posse Comitatus was definitely in the air. Schedule of Papers sent herewith…all men between the ages of 15 and 60…all live and dead stock…all persons willing to serve…Returns of all boats, barges, carts. Recruitment would follow. It would be by ballot, men called up for three years to defend their country.

I searched the papers and found the fading brown ink full of a new concern. What if the French already had spies in place? What if they were watching Britain, reporting every movement back to France?

The hunt for spies

The government knew to clamp down and prevent any possible revolution in Britain. New powers of arrest were implemented, all hint of revolution quelled. Radicals and dissenters needed to be rounded up, seditious meetings infiltrated and their organisers arrested. Those under suspicion would be imprisoned without trial. Spies would be hanged, and any form of corresponding with the enemy seen as treason.

Chief among the suspects were the French émigrés fleeing persecution in their thousands. My mind jumped to the morning’s news. In 1793, the émigrés were fleeing for their lives, warmly welcomed into Britain and given safe haven, yet what if those among them were spies, using the guise of fleeing persecution as cover? Border patrols were set up—a close surveillance kept on every French national entering Britain.

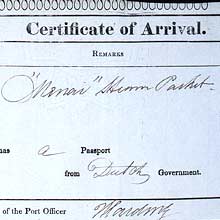

I started a new search and found The Aliens Act of 1793. Every French citizen needed to register at their port of arrival in Britain. Severe fines were levied for non-registration. The Alien Office was set up, a Superintendent of Aliens appointed to oversee the registration of all migrants. Detailed directions were given to all agents, mayors, and local officials regarding the detention or expulsion of migrants. Every alien was to hold a valid Certificate of Arrival.

I started a new search and found The Aliens Act of 1793. Every French citizen needed to register at their port of arrival in Britain. Severe fines were levied for non-registration. The Alien Office was set up, a Superintendent of Aliens appointed to oversee the registration of all migrants. Detailed directions were given to all agents, mayors, and local officials regarding the detention or expulsion of migrants. Every alien was to hold a valid Certificate of Arrival.

And so my book was born

The voices of my characters had begun speaking to me from the faded ink in the Truro Records Office, but someone was still missing. As I read the terms of the Aliens Act, a commanding voice began speaking across my mind, and I knew which way my book would turn. My story is set in Cornwall in 1793, but the troubles they faced then are just as relevant today—the threat to stability, the need for increased surveillance, even the suspicion that those we give refuge to may be spies.

*****

A big thanks to Nicola Pryce. She’ll give away a paperback copy of The Captain’s Girl to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Nicola Pryce. She’ll give away a paperback copy of The Captain’s Girl to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

“His handwriting was neat” – must have been Dundas on a good day! The King complained he had the hand of a rogue and I confess I tend to groan when I turn up his unmistakable spidery scrawl. Interesting post. Thank you!

Thank you, Jacqueline.

Nicola’s post really hits at the dilemma facing the British government in preventing Jacobin revolution at home. The logical step would have been to create a national police force to maintain control and disperse agitation but the government was convinced the activities of the French Ancien Regime police had caused such resentment they actually helped ferment revolution. Consequently, the only 8 police stations were in the Metropolis and for the rest of the country reliance was on untrained Parish Constables working for uncoordinated, amateur Justices of the Peace. Policy making in the Home Department was often hampered as London had no firm idea of what was happening elsewhere in the country. Justice could be arbitrary with Habeas Corpus suspended to allow imprisonment without evidence when revolutionary agitation was suspected and in the event of serious unrest the JPs had to call on the nearest Army or Militia troops (trained only in field warfare) to restore order. Fear of the ‘Terror’ and resurgent patriotism once war erupted in 1793 helped supress revolutionary fervour but the whole organisation was so amateurish when compared to modern standards it is a wonder the establishment prevailed.

Thank you Nigel for adding these fascinating details. I certainly got the sense of panic and muddle as I researched the documents. Cornwall was such a long and difficult journey from London which made law enforcement all the harder – it certainly was a wonder the establishment prevailed.

Really fascinating insights into how history repeats itself. Looking forward to reading the novel, Nicola. Thank you!

Thank you, Jenni. I hope you enjoy it.

Thank you for such a gripping, informative and insightful post, Nicola.

Thank you , Beverley. I love this period in history and find it fascinating.

Really interesting. You have portrayed both the rhetoric and the panic. To be prepared to pay a shilling a week indicates their concern. I don’t know much about this period of history, but have recently become interested in the plight of French refugees both as a result of the religious wars in France and the later revolution. I’m reading about recusants in Elizabethan England at the moment and it is, again, chilling how history repeats itself. I too could be looking at the current news, not news from nearly five hundred years ago.

Hi Paula. Yes very chilling. Your reading about recusants must be very interesting. There’s always the next thing to research!

Your blog intrigues me, but so do the cover and title of your book. I’m interested to see how that image and title plays into the book. (Off to look it up.)

That’s kind of you, Norma. I hope you like what you find.