Relevant History welcomes internationally renowned author Ellen Notbohm, whose work has informed, inspired and delighted millions in more than twenty languages. In addition to her award-winning novel The River by Starlight and her perennially popular books on autism, her articles and columns on such diverse subjects as history, genealogy, baseball, writing and community affairs have appeared in major publications and captured audiences on every continent. Ellen is an avid genealogist, knitter, beachcomber, and thrift store hound who has never knowingly walked by a used bookstore without going in and dropping coin. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes internationally renowned author Ellen Notbohm, whose work has informed, inspired and delighted millions in more than twenty languages. In addition to her award-winning novel The River by Starlight and her perennially popular books on autism, her articles and columns on such diverse subjects as history, genealogy, baseball, writing and community affairs have appeared in major publications and captured audiences on every continent. Ellen is an avid genealogist, knitter, beachcomber, and thrift store hound who has never knowingly walked by a used bookstore without going in and dropping coin. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Pinterest.

*****

The question comes up at every reading and book club: how and where did you research? And the answer is a historical fiction echo of Johnny Cash: I’ve been everywhere, man. My research for The River by Starlight and its based-on-real-life protagonists Annie and Adam Fielding sent me across eleven states and four provinces, through the doors of seventeen libraries and archives, and cyber-consulting twenty-seven more. I thought of it as a treasure hunt, unearthing vital statistics, school, military, prison, cemetery, land, court, census, immigration, naturalization, and theological records. Voter registration. Business licenses. Insurance policies. County and state fair entries.

For historical fiction authors, our drive for accuracy in the smallest details can border on obsessive. But after ten years in hot pursuit of those details, the resource that honed my manuscript’s voice to its finest edge of historical authenticity was a human, not a repository: an eagle-eyed editor with an exuberant love of etymology.

For scenes taking place between 1910 and 1921, I’d already caught early-draft anachronisms like surreal and radar. But my editor caught upwards of a dozen more. Who knew that no one shushed anyone until 1925, that place mats and drop cloths weren’t called such until 1928, that “dust mop” didn’t come along until 1953? That little girls didn’t wear their hair in a “ponytail” and jokes didn’t have a “punch line” until 1916. Jeepers! Whoops—that interjection wasn’t around until 1927.

Blue language: some things old, something things new

But most amusing was how many of her etymological catches had to do with that universally intriguing and bestselling subject: sex. And it offered a fascinating dichotomy: as we delved into the origins of blue language (an expression dating to 1840), we learned that words we think of as contemporary may go back centuries, while words we think of as vintage are in fact relatively contemporary.

Our etymological sex education started when Adam, in a 1911 scene, needed a sarcastic simile to express his contented state of mind to a bartender. “I’m happier than a baby in a barrel of tits,” he explains, which my editor flagged for revision: Teats was in use as early as the 13th century, titties dates back to 1746, but tits didn’t come into usage until 1928. Later in the story, another character’s reference to diddies was revised to diddeys, per Merriam-Webster.

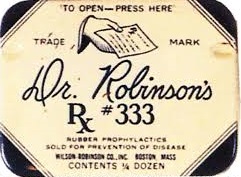

On rolls the story to where, in the face of relentless physical and mental health issues with Annie’s pregnancies in the 1910s, the couple is advised to consider using rubbers. “The condom sense of this word dates only to the 1930s,” said my editor, suggesting maybe I should revert to condom (1706). I hauled out my (highly entertaining) file of early condom advertisements, and noted that while all the packages used the terms rubber prophylactics or protectives, none used the word condom. Further research revealed that the, um, contents of a condom were the origin of one of today’s favorite insults, scumbag (1939). We settled on rubber sheath (1861).

On rolls the story to where, in the face of relentless physical and mental health issues with Annie’s pregnancies in the 1910s, the couple is advised to consider using rubbers. “The condom sense of this word dates only to the 1930s,” said my editor, suggesting maybe I should revert to condom (1706). I hauled out my (highly entertaining) file of early condom advertisements, and noted that while all the packages used the terms rubber prophylactics or protectives, none used the word condom. Further research revealed that the, um, contents of a condom were the origin of one of today’s favorite insults, scumbag (1939). We settled on rubber sheath (1861).

Later still, Annie finds her virtue questioned by a mental hospital patient who hurls the insult, “Slattern!” (1630s). Not one to go quietly, Annie returns a fusillade of loose-woman epithets. Up went the editor’s flag. Seems that harlot (ca 1200), strumpet (ca 1300), trollop (1610s), hussy (1650s), and floozy (1902) were appropriate to the 1918 scene, but tramp met with the delete button because its meaning “promiscuous woman” dates only to 1922.

Surely things would mellow out for our heroine as she overcomes extreme adversity, settles into a placid spell, and can enjoy some long-overdue tender lovemaking. But no. Said my intrepid editor, “While this word has been around since the fifteenth century, its original sense was of courtship. As a euphemism for ‘have sex,’ it is attested only from c. 1950.” Disgruntled Author changed it to coupling (late 1300s), muttering that it sounds too much like hardware.

Charting word usage through time

Frequency of usage is also a factor in historical authenticity. Tools like Google Ngram use charts to visually depict word usage over centuries. Here we can see just how much that usage of the f-bomb, that ultimate in sexually-charged verbs, now turned everyday adjective, has increased—by a whopping (1620s) 23,000% since 1950. Before that it had nearly flatlined since 1820 or so, hence it pops up only once in dialogue in The River by Starlight—as an unintended double entendre, with great impact bestowed by its rarity.

But our free-wheeling contemporary use of the f-word doesn’t hold a fadoodlin’ (1611) candle to our bawdy ancestors, who in the mid-1600s used it at twice the rate we do today.

Hubba-hubba (1944)!

Resources:

o Online Etymology

o Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (11th edition), Merriam-Webster Unabridged (website)

o A Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English, Abridged from the Seven-volume Work, Entitled: Slang and Its Analogues (Farmer & Henley, 1905)

o Dictionary of American Regional English (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1985)

*****

A big thanks to Ellen Notbohm. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The River by Starlight to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Ellen Notbohm. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The River by Starlight to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Ann Parker, whose Silver Rush mystery novels originate in Colorado, posts weekly about her search for historical accuracy in word usage. It is fascinating. I think Ann would find your post most insightful.

It sure is fascinating. I can’t count how many times I went off on flights of curiosity, following a word back in time. I’ll check out Ann–thanks for the tip. Another source–and kindred etymological soul–is always welcome.

Thank you for mentioning my blog, Liz!

And thank you for a fascinating and entertaining post, Ellen! I, too, love Ngram. Your book, The River by Starlight, sounds right up my alley (hmmm… now when did *that* term come into use, I wonder…)

Fascinating! As someone who also spends a lot of time worrying about words out of time, that was immensely interesting.

I’m normally not a fan of worry, but once a book is in print, it’s hard to live down the one anachronism we missed. So this is a well-placed worry, or let’s call it “motivation.” A writer friend recently gagged over a historical novel whose character said, “My bad!”

Sigh. Another bookmark on my lengthy list of places to research. Thanks for this. So interesting.

I hope that was a happy sigh.

I need to find out more about that Google Ngram thing. Sounds enormously useful! But I will keep fadoodlin’ in mind. I love cusswords that don’t sound like cusswords.

Ngram isn’t the only one, and of course it has its detractors. For this reason, we used multiple sources. I found many sites that gleefully list archaic ways to refer to sex. However, the one I use most in private life came from a Texas friend– “bumpin’ fuzzies.”

Some are “bumpin’ bald.” 😀

As long as they’re not “bumpin’ bad.” 😀

Fascinating to read about how vocabulary has evolved over the years. It’s great that you have an editor to research all those usages that many would take for granted!

Yes, my editor is worth her wait in wampum.

You have a good editor. Few subjects are as interesting as language and the changes wrought by time. One of my go-to resources on the subject is The Oxford Dictionary of Word Histories, but even that isn’t absolute (late Middle English).

I do indeed have a great editor, who in turn makes me a better editor. But “absolute” is probably not in the realm of reality if we’re talking about the wildering English language, yes?

So interesting! I never heard of fadoodling! Perhaps it’s time for a resurgence! I use Merriam Webster online, but some of the other resources sound more meaty. Thanks!

I liked fadoodling better than “shot twixt wind and water” and “riding below the crupper.” Ewww! Some folks really know how to kill romance.

No kidding!

So fascinating, and hysterical!And I never heard of Google Ngram. So I’m trying to remember if Pepys used the f word all the time…

A greatly informative and amusing piece 😍

Well, yes. He did. Search keywords Pepys with the f-word and you’ll get a great little piece on theappendix.net

f’n good read!

Thankee!

I love this kind of thing! Some of my favorite books are about etymologies and usage, like The King’s English by Kingsley Amis and Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries by Kory Stamper.

Yes! Secret Life is word nerd heaven.

When I am in doubt, I go to Oxford English Dictionary at our college library. It helps a great deal, but not for deeper research. I recently read a historical by a well-respected author. The men in his sailing, whaling ship, threw their mattresses overboard. Wait. I think they slept in hammocks. :/

Then they probably fadoodled in hammocks too? Early version of waterbeds?