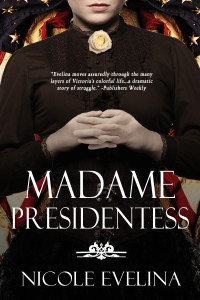

Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Instagram, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Instagram, and Pinterest.

*****

When we think about the suffrage movement, a handful of “greats” come to mind, the leaders who shaped and changed the movement: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, Carrie Chapman Catt. But each state had their standouts, women without whom state ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment may never have happened.

In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet.

In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet.

Instead of wasting away, Virginia channeled her rage and pain into fighting for women’s rights in Missouri. On 8 May 1867, she and four other women founded the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri, the world’s first organization dedicated solely to women’s suffrage. (It pre-dates the National Woman’s Suffrage Association, NWSA, founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the American Women’s Suffrage Association, founded by Lucy Stone, by two years.) Virginia served as the organization’s first president and spent the next two years petitioning the state legislature in favor of woman suffrage.

The New Departure

In October 1869, the NWSA convention in St. Louis, Virginia first made the argument that would change the suffrage movement and later be dubbed the “New Departure” because it was so different from anything the suffrage movement had seen to date. Citing the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, ratified only months before, she argued that women already had the right to vote, saying, “I believe the Constitution of the United States gives me every right and privilege to which every other citizen is entitled; for while the Constitution gives the States the right to regulate suffrage, it nowhere gives them power to prevent it.”

The passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in question states:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Virginia’s argument, which would later be taken up by Victoria Woodhull during her presidential campaign, as well as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony when they addressed Congress, stated that the use of the word “persons,” rather than “males” is what allowed female suffrage. She and her husband printed pamphlets to this effect which were circulated throughout the United States. Susan B. Anthony even reprinted her argument in her newspaper, The Revolution.

Seeking to practice what she preached, Minor put her theory to the test on 15 October 1872, when she tried to register to vote. But the election registrar, Reese Happersett, would not allow it because she was female. In response, Minor, with her husband as her representative (married women could not yet sue in Missouri courts; that right would come in 1889 with the Married Woman’s Act), sued.

On 3 February 1873, arguments were heard in writing at the Old Courthouse in St. Louis without a trial or jury. The trial court ruled against the Minors, so the case was brought before the Missouri Supreme Court, who heard the case and ruled against the Minors.

Not ready to give up, Minor and her husband appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which gave the case the legal name, Minor v Happersett. Francis Minor gave an impassioned argument that denial of suffrage happened all the time, but that because national citizenship superseded state citizenship, women should be allowed to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment, regardless of what their local state laws said. He pointed to history, particularly to the example of the women of New Jersey, who had the right to vote from 1787 to 1807, to shore up his argument.

On 29 March, the Supreme Court refuted the argument, upholding the right of individual states to define who could vote within them, stating in a unanimous decision “that the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon any one” rather that right belongs to the states. It ignored the fact that although women were citizens under the law, they didn’t have the same rights, and effectively ended the hope of a national judicial decision in women’s favor.

Persevering to the end

Though Minor’s court case failed, it gave great publicity to the cause of women’s suffrage, and Virginia kept fighting for what she believed in. She testified before the United States Senate committee on woman’s suffrage in 1889 and held the position of honorary vice president of the Interstate Woman Suffrage Convention in 1892.

When Virginia died in St. Louis two years later, she was buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery. Because she believed the clergy were against equal rights for women, her funeral was held without any clergy members, a final thumb of her nose at the patriarchy.

In a break with tradition that said a person’s final will and testament should be kept private, Virginia’s will was published in the St. Louis newspapers because it contained two unusual bequests. Virginia left $500 apiece to her two single nieces, with the condition that if they should ever marry, the married niece should surrender her half of the inheritance to the niece who remained single. Another $1,000 was bequeathed to Susan B. Anthony “in gratitude for the many thousands she has expended for woman,” to help ensure the fight for women’s suffrage could continue on beyond Virginia’s lifetime.

*****

A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about Victoria Woodhull (nominated in 1872 as the first woman candidate for the United States presidency and a contemporary of Virginia Minor who likely knew her) to one person who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about Victoria Woodhull (nominated in 1872 as the first woman candidate for the United States presidency and a contemporary of Virginia Minor who likely knew her) to one person who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Three thoughts come to mind. One is that for a woman with such a smart, supportive husband her bequest to the nieces seems strange. But perhaps not since so many single women struggled financially. The second is that Native Americans didn’t have citizenship until after WWI when many signed up to serve overseas. Therefore, they couldn’t vote regardless of being born in this country, albeit on tribal or reservation lands. We’ve come a long way in terms of Civil Rights thanks to women like Minor. Now to keep going.

Hi Karen,

It is my understanding that Virginia chose to support her nieces to show them they did not have to get married to survive financially, a very radical notion in the late 1800s. I agree on your comment about Native Americans. Suffrage is much more nuanced than we tend to think of it. African American women, especially in the South, really didn’t get to vote until after the Civil Rights movement, even though they were technically included in the Nineteenth Amendment.

Many women who were in favor of women’s voting rights were also Abolitionists and supported other social reforms before and during the Civil War.

Yes! That is how they got their start – learned how to organize and speak in public. The ties are fascinating.

It’s so sad that it took until the 19th Amendment to make votes for women happen. Right after women largely spearheaded Prohibition.