What if the ideal weapon to off that disagreeable person in your life was in your corner drugstore—and untraceable back to you? True crime and historical mystery author Kathryn McMaster discloses the surprising history of arsenic’s use and abuse in the 19th century.

~~~

Relevant History welcomes Kathryn McMaster, a writer, entrepreneur, wife, mother, and organic farmer. She is also a bestselling author of historical murder mysteries set in the Victorian era, and modern true crime cases based on Canadian and American murders committed by young teens and couples. She co-owns the website One Stop Fiction, where readers can download free and discounted 4- and 5-star review books, and authors can showcase their work. She lives on her thirty-acre farm in the beautiful Casentino Valley, Italy where she divides her day between researching, writing, gardening and farm work. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes Kathryn McMaster, a writer, entrepreneur, wife, mother, and organic farmer. She is also a bestselling author of historical murder mysteries set in the Victorian era, and modern true crime cases based on Canadian and American murders committed by young teens and couples. She co-owns the website One Stop Fiction, where readers can download free and discounted 4- and 5-star review books, and authors can showcase their work. She lives on her thirty-acre farm in the beautiful Casentino Valley, Italy where she divides her day between researching, writing, gardening and farm work. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest.

*****

When I was at school learning about the Victorian Era of 1837–1901, we were taught about the social impact and impoverishment the Industrial Revolution brought to certain sectors of society when machinery replaced manual labor. What we were not taught was how prevalent arsenic was during this period in the production of household goods, fabric, and even beauty products used by those in the upper echelons of society.

When I was at school learning about the Victorian Era of 1837–1901, we were taught about the social impact and impoverishment the Industrial Revolution brought to certain sectors of society when machinery replaced manual labor. What we were not taught was how prevalent arsenic was during this period in the production of household goods, fabric, and even beauty products used by those in the upper echelons of society.

When I started researching certain murder cases for my earlier novels that are set in this era, I stumbled upon this very different social aspect of Victorian living. It was rather fascinating just how common arsenic was and how difficult it was at the time to detect its use as a choice of murder weapon, used more often by women.

With the symptoms of arsenic poisoning often confused with cholera, these types of murders were very difficult to detect, even with an autopsy.

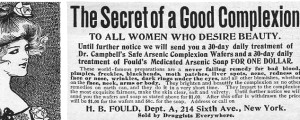

Arsenic was everywhere! It was prevalent in paints using Scheel’s Green for the green pigments. It was found in wallpaper, fly strips, and even impregnated in clothing fabrics and curtains.

Not all pharmacies enforced a poisons book. So, if you bought arsenic, you did not always have to sign for it. In addition, in some factories the arsenic lay in large, uncovered barrels placed in unsecured areas. It was therefore readily accessible to workers and impossible to detect if a teaspoon, a tablespoon, or even a cup of arsenic was missing at the end of the day.

My second book, Blackmail, Sex and Lies, covers the life and times of the infamous socialite Madeleine Smith, accused of poisoning her working-class lover, Pierre Emile L’Angelier with arsenic. The book highlights the accessibility of this poison and how it was a common ingredient in many household products; this casts doubt on her guilt, especially as L’Angelier took arsenic as a health benefit!

During this time in history it was discovered that by giving horses arsenic in small amounts it gave them stamina which enabled them to endure long distances. People started to dabble and found that in small doses it did the same for them. Arsenic then began to appear as an ingredient in beauty wafers and soaps. Articles in popular magazines such as Blackwoods encouraged women to bathe in it to soften their skin.

During this time in history it was discovered that by giving horses arsenic in small amounts it gave them stamina which enabled them to endure long distances. People started to dabble and found that in small doses it did the same for them. Arsenic then began to appear as an ingredient in beauty wafers and soaps. Articles in popular magazines such as Blackwoods encouraged women to bathe in it to soften their skin.

With L’Angelier eating arsenic, and Madeleine Smith using it as a beauty wash during the time he conveniently died when a much wealthier suitor arrived on the scene, there is great doubt as to who or what had killed him. Although the coroner was able to count the arsenic grains inside L’Angelier’s stomach, with limited forensic knowledge and a lack of access to more modern science, Madeleine Smith may well have gotten away with murder. In the end, the case was not proven, which meant that for time immemorial, it has been a case of, ‘did she, or didn’t she?’ The answer only Madeleine Smith knew for sure.

Although police had fingerprinting and other presumptive tests for blood evidence etc., forensic science during the Victorian era was still in its infancy. Due to rudimentary police training and the absence of modern forensic science, many arsenic crimes went undetected and unpunished.

*****

A big thanks to Kathryn McMaster! She’ll give away one paperback copy of Blackmail, Sex and Lies to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Kathryn McMaster! She’ll give away one paperback copy of Blackmail, Sex and Lies to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

A fascinating subject, Kathryn. When I began reading, I was reminded of the story, Madame Bovary, who had ingested arsenic because her lover spurned her and she had ruined her husband’s life. Your extensive research about how prominent the arsenic product was during the Victorian Era is impressive. I hadn’t realized there was a fine line between using arsenic for both health benefits and poison during that time. Forensics sure has come a long way since then.

It has indeed, Alice. Thank you for your lovely comments.

Madame Bovary came to my mind too, but also the much later episode of the poisoning of Ambassador Claire Boothe Luce by paint chips falling from her bedroom ceiling.

Yes, Liz, you are absolutely right, as that was in Italy, in 1955. I am guessing the Italians were a little tardy in updating the decor!

Fascinating stuff! I also love the free use of cocaine in tonics of the era and a little opium here and there. Your book sounds intriguing, Kathryn.

Including advocating it for babies to soothe their aching gums! How times have changed. Thanks for making contact, Edith.

Sounds like I’ve found a new author to read. Fascinating!

Thank you, Teri. I do hope you enjoy reading my books.

Really interesting article.

I have added your name to my TBR list. Your books sound interesting and the kind I would enjoy reading.

Thank you, Joy!

I wonder what the modern equivalent of arsenic is as an undetectable means of disposing of the unwanted and the unloved? Perhaps you shouldn’t answer that in public!

Possibly polonium, Charlotte. It is very difficult to detect. However, thankfully, it is not nearly as accessible as arsenic was.

Hi Kathryn , I recently saw s story about the arsenic in wall paper and how a homeowner of a Victorian home was affected by the arsenic . A modern day version of this is the ingestion of lead paint , paint chips which are sweet to taste .So young children will eat it because it tastes good . Your plot line is interesting, can’t wait to read your books !

Hi Betsy, the Victorians loved their dark green decor, but unfortunately inside the paint and wallpaper was a copper-arsenic component found in Scheel’s green that was used for the pigment. In wallpaper, once the walls behind it became damp and moldy, the wallpaper degraded and an arsenic gas was released. Lead paint is indeed a modern day equivalent of this. Asbestos, of course, is another. Thank you for you comments and I do hope you enjoy my books.

It seems anything that “preserves” items, food, etc. from decay or pests is eventually found to be problematic for people too. Thus the increase of organic foods and cosmetics.

As someone who raises organic food, I completely agree, Karen.