Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Relevant History welcomes Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He has written numerous articles and three books on the subject, using primary sources to reveal personal information about British soldiers and their wives in America. His fourth book, British Soldiers, American War will be released from Westholme Publishing in November 2012. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers, and his books are available from Revolutionary Imprints, also a source for first-hand accounts of the American Revolution.

Relevant History welcomes Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He has written numerous articles and three books on the subject, using primary sources to reveal personal information about British soldiers and their wives in America. His fourth book, British Soldiers, American War will be released from Westholme Publishing in November 2012. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers, and his books are available from Revolutionary Imprints, also a source for first-hand accounts of the American Revolution.

*****

John Row was a British officer in the 9th Regiment of Foot, and he was in love with Jenny Innes. For six years their courtship was maintained largely by correspondence due to separations during his military career. I recently perused dozens of their letters that survive in the National Archives of Scotland, revealing a touching love story and a surprising visual treasure.

Row began writing to Jenny from Dublin in 1775, soon after they had met. They hadn’t made their mutual interest known to her family and agreed to limit their correspondence so as not to arouse suspicions. The next year, however, saw the 32-year-old officer embarking to join the war in America, bound for “Quebec which is not the worst Country in the World.”

Row’s letters from America are not particularly informative. (A soldier in his regiment, Roger Lamb, left a detailed chronicle of the 9th Regiment’s service. Lamb later transferred to the 23rd Regiment and Cornwallis’s army, and his chronicle includes details of his military action in the Southern theater.) From Quebec, Row apologized in letter after letter for writing so frequently, since he did not know when the next opportunity would arise. A long winter in lonely isolated quarters curtained their correspondence, which resumed only briefly in the spring of 1777 before a new campaign began. In the mean time Row had received only one letter from Jenny since departing Ireland, and he feared for her health as she battled respiratory complaints.

It was Lt. Row’s own health, however, that caused the next hiatus. In November 1777 he wrote from London, informing Jenny that he had been wounded in the right knee at the Battle of Hubbardton on 7 July 1777. In Great Britain to recover, he hoped to return to his regiment in the spring. The campaign he’d left had gone badly, though, and the 9th Regiment was in captivity after the British capitulation at Saratoga. Row returned to Scotland, spent time with Jenny and negotiated with her family. This sojourn was a short one, however, as Row had his career to attend to.

There was nothing in Britain for a zealous officer determined to distinguish himself. In 1779 Row was able to obtain a captain’s commission in a new regiment, the 85th Regiment of Foot, being raised for service in the rapidly-expanding war. Jenny objected to his choice, for not only would it keep them apart but it also stood to put him at risk if the regiment was sent abroad. He nonetheless related details of his recruiting and training activities.

Within a few months the 85th Regiment was fit for service and received orders for the West Indies. Jenny was mortified and wrote a long letter expressing her dire concerns for her beloved’s fate. Hadn’t he already risked enough and suffered enough? Not only would the climate be his enemy, but he would be exposed to greater danger because the effects of his wound made him less adroit than younger officers. Having stated her misgivings, she agreed to say no more on the subject.

As the 85th was preparing to embark, a painter arrived at the port offering his services to officers who knew they might be leaving their homeland for the last time. Row commissioned a portrait for Jenny, which the artist prepared for by using a projection machine to create a silhouette. Row mailed the silhouette to Jenny on 30 March 1780, and this rare image remains enclosed in the letter to this day. Seen here, it is a fascinating look at this man who zealously sought to balance love for a lady and a career.

As the 85th was preparing to embark, a painter arrived at the port offering his services to officers who knew they might be leaving their homeland for the last time. Row commissioned a portrait for Jenny, which the artist prepared for by using a projection machine to create a silhouette. Row mailed the silhouette to Jenny on 30 March 1780, and this rare image remains enclosed in the letter to this day. Seen here, it is a fascinating look at this man who zealously sought to balance love for a lady and a career.

Or, at least, it might be John Row. Row’s own comments about the silhouette cast interesting doubts on the likeness:

My Dear Jenny,

Inclosed I send you my shade in profile but which from my opinion of it is either badly taken, or else I make a very bad one which the person who took it tells me is the case of every one who has not high features…I appear the most stupid insipid looking fellow imaginable, and to compleat my mortification every one tells me that it is a most striking likeness.

In a subsequent letter Row went so far as to suppose that the artist had accidentally given him the silhouette of another officer. Jenny made no comment on the silhouette, but when she received the portrait she was as unimpressed with it as she was with his decision to go overseas. She wrote:

I was somewhat disappointed with the Crayon as I do not think it a favourable likeness especially in the under part of the face, in the upper it resembles you more & place it at a considerable distance & it is certainly upon the whole like, but it is a bad resemblance coarsely done & with materials which discolour & fade very soon. I however return you my thanks for it such as it is…

It is unfortunate that Jenny was so indifferent to the portrait, for it was the last image of her suitor that would ever greet her eyes. Her fears about John Row’s safety were realized. He died in September 1780, just ten weeks after arriving in the West Indies, victim not to battle but to contagious diseases that carried off nearly half of his regiment.

*****

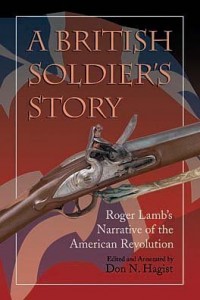

A big thanks to Don Hagist. He’ll give away an autographed copy of A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution in trade paperback format to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on my blog today or tomorrow. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Tuesday 3 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 3 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Thriller.

A big thanks to Don Hagist. He’ll give away an autographed copy of A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution in trade paperback format to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on my blog today or tomorrow. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Tuesday 3 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 3 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Thriller.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

A fascinating story. I always love stories like that – it adds a human element to the conflict that very few history books or books in general seem to mention.

Welcome to my blog, Matt! I agree with you. For most Americans, the Revolutionary War approaches the status of classical mythology, with larger-than-life heroes battling larger-than-life villains, and the losses being counted in terms of corpses on battlefields. Don’s post reminds us of the humanity in history, of the loss endured by loved ones whenever a soldier died.

Don, thanks for your excellent post. I’m curious…Jenny had waited on John Row for six years. What happened to her after he died? Did she marry?

With only a limited amount of time to work with this manuscript collection, I only scratched the surface of the story. I know nothing of Jenny’s life before, during or after the courtship, or of John Rowe’s background before he joined the army. I don’t know why they were compelled to keep their romance secret initially. I hope someone feels inspired to read the letters in detail and do additional research on these two individuals.

I’m not the only one lamenting that you didn’t have more time in the National Archives of Scotland, Don. The piece of John and Jenny’s story that you’ve revealed is a fascinating peek into the personal life of a soldier. And it’s the kind of biographical “scoop” that rises on the New York Times bestseller list.

Part of what makes this story so memorable is John’s silhouette. Even if his suspicions were correct, and it isn’t his silhouette, it still belongs to some soldier from 1780, so it gives us a glimpse of a person who was alive more than 230 years ago. In that respect, it reminds me of the forensics reconstruction of Private James Simpson, whose remains were found in Canada at Ft. Anne. You played an integral part in that project by producing muster roles to help identify the soldier.

How very interesting. It was tough being a soldier in that time but options were limited. I wonder if he was a younger son and if he bought his commission.

Thanks for commenting, Warren. I also wondered how John Row came by his lieutenant’s commission. It looks as though he figured the system out so he could advance to the captaincy.

That was interesting, I really liked the quotes. The comment about Quebec looks so modern to me, it would easily be a part of an internet meme. I also liked Row’s bemoaning the silhouette, poor guy. I hope Jenny was able to recover from losing Row.

I’ve heard of the high casualty rate of the West Indies was such that the nickname for it was the Fever Islands. I also read that being posted there was not considered a good posting at all; that those who sought such a posting only did so for a chance to get promoted more quickly.

Hi Mel! There is a modernness to much about the Revolutionary War that sneaks up on you and surprises you, reminds you that some things about humans don’t change over the millennia. The first time I read John Row’s gripe about his silhouette, I chuckled. It reminded me of the way everyone complains about driver’s license photos.

Tracy, I’ve read that about the Caribbean, too. Although you could get malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and numerous other killer fevers in the Southern and Northern theaters, too — not to mention the Asian theater. September, the month in which John Row died, a lot of those diseases would be in full rampage. No doubt he took all that into consideration in his gamble to advance in rank.

You’ve given me a great platform to plug my new book, Tracy! “British Soldiers, American War” (http://www.suzanneadair.typepad.com/blog/2012/07/the-courtship-of-lt-row-and-jenny-innes.html/) includes a chapter about a soldier who served in the West Indies, in the 85th Regiment of Foot, including some of the glamorous promises of fortune made by recruiters to induce men to enlist for these difficult climates. In most cases, though, men did not seek their postings; they joined a regiment for whatever reason, and then went where it was posted, sometimes to their chagrin. In a case like Row’s, he certainly joined the 85th Regiment because he could advance his rank by doing so, but he did not know at the time that this new-raised corps would be sent to the West Indies. In his letters to Jenny he tried to make the best of it, but one wonders what the conversation was like among his fellow officers when they learned where they were going.

Oops! Here’s the correct link to the new book (note: always copy before pasting):

http://www.westholmepublishing.com/british-soldiers-american-war.php

Don–thanks so much for humanizing the Brits for us Yanks; Suzanne does that so well in her fiction, but I am now anxious to delve into the non-fiction accounts.

Somehow we forget that “the enemy” also leaves a family behind…and it seems the military was one of the few occupations then that actually did allow a man to advance his status in life (if he managed to live, unlike poor John).

Which leads to a question–would his survivors (if any) be entitled to a stipend of some sort from George III?

I look forward to reading British Soldiers, American War. In the mean time, the book Don’s giving away, A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution, is excellent reading.

Don begins with a brief introduction to Roger Lamb. He supplies general background about the organization of the British Army and a soldier’s uniform and equipment. Then he turns the book over Lamb, who wrote journal entries that are very readable, even today.

Roger Lamb himself was probably not a typical soldier. He advanced quickly in rank, had a superior education, and was offered opportunities to learn a variety of skills in the Army. However his journal provides crucial insight into the life of typical British soldiers during the American Revolution.

And it’s about time we had that insight. What Lamb left us in his journal humanizes the common British soldier and demolishes the stereotype of him as a brutish criminal. And what Don did with Lamb’s journal proved to be a spirited call for other researchers. As I said, excellent reading.

Linda, you’re really enjoying yourself with these posts.

Don, I know a lot of loyalists petitioned the Crown for assistance with their losses in America but were never compensated. Clearly the Crown was tight when it came to compensation. So Linda’s question interests me, especially when it comes to helping widows of officers killed while in America.

I read somewhere of British regiments having procedures in place to make certain that the widows of officers who had died in combat on American soil received safe transportation back to Britain. Was this on your blog? Remarkable.

For information about soldiers’ wives, see my article here: http://revwar75.com/library/hagist/

It is, with all due modesty, the best source of information on the subject. It focuses, however, on wives of common soldiers, not of officers.

Had John Row been married to Jenny, she would’ve been entitled to an officer’s widow’s pension. As it was, there’s no evidence that John had any dependents. The British army had a tradition of selling a deceased officer’s effects at auction (the buyers usually being other officers); the proceeds were used to settled his outstanding debts, and whatever assets remained were returned to his family in Great Britain.

I enjoy reading stories about the soldiers and their personal lives. I am going to check out Don’s other articles and books. The history of our County and the men and women who fought is one of my greatest pleasures.Thank you. Happy 4th everyone.

Carol L

Lucky4750 (at) aol (dot) com

Carol, after you start reading, you’ll be hooked. Don does such a great job of bringing those soldiers to life. It’s almost like sitting down and chatting with them.

Don does such a great job of bringing those soldiers to life. It’s almost like sitting down and chatting with them.

Don, your example of Lt. Row in the West Indies was very interested. I am currently writing a book on Concord, Massachusetts in the American Civil War and have a chapter on the colonial era of the town, including the military history. I found a reference to an expedition launched in 1740 of Massachusetts soldiers to the West Indies. 500 men were part of the expedition. The men were discharged in 1742 after returning back to Massachusetts. Of the 500 men that were part of the expedition, only 50 men had survived. It was such a disastrous expedition that formal investigations were launched by the colonial government.

Only 50 out of 500, Matt? Wow. Those guys would almost have fared better pitted against a firing squad.

Yes, that would be the same West Indies that Lt. Row went to.

To give another example – from my new book – the newly-raised 88th Regiment of Foot mustered 762 men (not including officers) in October 1778. They went to the West Indies in early 1780, along with Row’s 85th Regiment. In March 1782 they mustered 294 men, of whom about half were sick – and they had received a number of recruits in the mean time.

It bears noting that, on those rare occasions when the British did actually offer men military service as an alternative to prison, the men to whom this was offered were usually sent to places like the West Indies where the mortality rate was horrendous.

Thanks for the additional information, Don. What were the most common infectious diseases to kill these soldiers?

I have an undergraduate in Microbiology and know that prior to the mid-20th century, the most common cause of death was infection. But I still find mortality rates like these stunning.

I haven’t tried to research the specific illness that felled British soldiers in the Caribbean. My guess is that it was mosquito-borne fevers such as malaria and dengue, the same things that are scourges to this day. Many books were written during the 18th Century concerning the health of soldiers (some available on CD-ROM here: http://revolutionaryimprints.com/ricd123-military-medical-and-religious-te123.html) but the names used then don’t always match what we use today.

It’s a great thing to study, but nothing something I’ve devoted any time to.