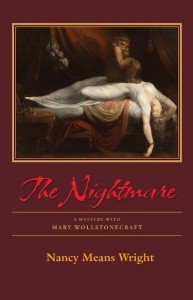

Relevant History welcomes Nancy Means Wright, who has published sixteen books, including five contemporary mystery novels from St Martin’s Press, and most recently two historicals: The Nightmare: A Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (2011) and its prequel, Midnight Fires (Perseverance Press, 2010). Her children’s mysteries received both an Agatha Award and Agatha nomination. Poems and short stories have appeared in American Literary Review, Green Mountains Review, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Level Best Books, and elsewhere. Longtime teacher and Bread Loaf Scholar for a first novel, Nancy lives with her spouse and two Maine Coon cats in Middlebury, Vermont. For more information, check her web site.

Relevant History welcomes Nancy Means Wright, who has published sixteen books, including five contemporary mystery novels from St Martin’s Press, and most recently two historicals: The Nightmare: A Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (2011) and its prequel, Midnight Fires (Perseverance Press, 2010). Her children’s mysteries received both an Agatha Award and Agatha nomination. Poems and short stories have appeared in American Literary Review, Green Mountains Review, Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Level Best Books, and elsewhere. Longtime teacher and Bread Loaf Scholar for a first novel, Nancy lives with her spouse and two Maine Coon cats in Middlebury, Vermont. For more information, check her web site.

*****

How many poets, writers, and artists were undervalued during their lives, even scorned, and only posthumously called genius, classic, great? I think, among others, of the reclusive Emily Dickinson who published a mere handful of poems in her lifetime, or eccentric Vincent Van Gogh who sold only a single painting, cut off his ear, and was considered mad.

Few, it seems, were as misunderstood and maligned as 18th-century Mary Wollstonecraft. Her groundbreaking Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was greeted with cries of outrage when she called for co-education for girls with boys, and for female political, economic, and legal equality. Marriage she declared, was “a slavery; arranged marriages a legal prostitution.” For that, they called her a “hyena in petticoats,” a “philosophical wanton.” Even her own sex belittled her: “There is something absurd in the very title,” the conservative writer Hannah More said of Vindication; “I am resolved not to read it!”

Some of her disrepute came about through her own conflicted character. Her open-mindedness and impetuosity, along with her intolerance of sham and injustice, made her an easy target. She rescued her younger sister from an abusive marriage—and society called it “kidnapping.” She compelled a biased English captain to rescue a sinking boatload of French sailors, and was labelled “presumptuous.” As governess, she taught her pupils to love Shakespeare and to think for themselves, but was dismissed when her aristocratic employers claimed she’d neglected to teach their daughters to embroider—and worse, had stolen their affections from the neurotic mother.

“I want to live independent or not at all!” Mary cried as she fled to London with the manuscript of her first (autobiographical) novel.

Her life was a struggle between her principles of independence and her passions. In London, she horrified society when she sought a platonic ménage à trois with artist Henry Fuseli and his pampered wife. In revolutionary Paris, with heads rolling from the guillotine, she lost her own head to the dashing American captain, Gilbert Imlay. To Mary, still a virgin at 34 when he bowled her over, the act of love was “wholly sacred.” When she got pregnant, Imlay abandoned mother and illegitimate child to the taunts of society. Her attempts at suicide after the betrayal caused yet more scandal. Back in London, doors slammed in her face.

Finally, honest William Godwin came along, to offer genuine love and commitment. Their short happy marriage ended in the birth of daughter Mary (who later wrote Frankenstein)—and with the young mother’s death. Yet writer Godwin naively added shovelfuls of coal to the public fire with a posthumous memoir in which he gave full, unverified details about his late wife’s relationships with Fuseli, and then with Imlay and their illegitimate child, Fanny. Godwin praised her rejection of organized religion but neglected to mention her belief in God and her deep spiritual nature. Mary’s letters show her as loyal, loving, and monogamous, but horrified Londoners saw only an atheist and a wanton, an unwed mother involved with three men—even simultaneously, according to salacious rumor.

The slander persisted throughout the 19th century and into the 20th. Although a few carefully researched biographies came out in the late 19th century, it has only been since the mid-to-late 20th century that a flurry of biographies have shown Mary to be the highly original, intelligent, compassionate woman that she truly was. She made some crazy mistakes in her life as we all do, but always owned up to them, and came through her trials with remarkable resilience.

Feeling her to be an admirable sleuth through her intolerance of sham and injustice; and determined to clear up falsehoods and to bring her to full life, I began a series of mystery novels with Mary Wollstonecraft as protagonist. One might call it a Vindication of Mary! In Midnight Fires she is a beleaguered young governess to the notorious Kingsborough family. In The Nightmare, just out from Perseverance Press, her quest for truth leads to a madhouse chase to free a man accused of stealing Fuseli’s famous painting, “The Nightmare,” and to discover the rogue who strangled a woman to resemble that painting. Book 3 will take her to revolutionary Paris, “neck or nothing!” as she famously declared—and to meet the rogue Imlay.

Mary once wrote her sister that she was going to be “the first of a new genus of woman,” and so, despite the misconceptions and overwhelming odds, she was.

*****

A big thanks to Nancy Means Wright. She’ll give away one paperback copy of The Nightmare and two paperback copies of Midnight Fires to people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose three winners from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within Canada and the U.S.

A big thanks to Nancy Means Wright. She’ll give away one paperback copy of The Nightmare and two paperback copies of Midnight Fires to people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose three winners from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within Canada and the U.S.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.