Relevant History welcomes Rebecca Lochlann, who is busy working on her historical fantasy series, “The Child of the Erinyes.” The first book, The Year-god’s Daughter, is an Indie B.R.A.G. Medallion honoree and was recently utilized as a university class study guide. The series centers around a small corps of protagonists who begin their lives in the Bronze Age Mediterranean, draw the attention of the Immortals, and end up traveling through time. Right now Rebecca is deeply immersed in Queen Victoria’s world as she edits book four, The Sixth Labyrinth. You can read more about Rebecca’s books and find links to a trailer, bibliographies, and excerpts on Rebecca’s web site. For additional information, visit her Facebook page.

*****

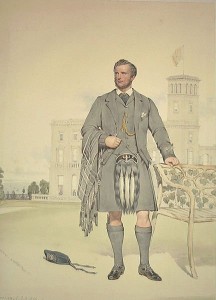

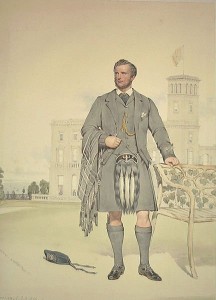

There are many articles and biographies about John Brown, the Scotsman who served Queen Victoria before and after Prince Albert’s death. He’s portrayed as a rough, ill-mannered gillie, a servant and one-time stable boy, who yet managed to charm the widowed queen out of her grief, at least somewhat. He is said to have been a heavy drinker, uncouth, rude, smelly, even “insufferable.” One reason this story captures our interest is because Queen Victoria has an ongoing reputation, true or not, of being the epitome of propriety, notorious for not allowing any unorthodox behavior or speech in her presence—except when it came to John Brown. He, apparently, could do no wrong.

Most rumor mills keep things PG, but some suggest she and Brown were lovers. There are even claims she secretly married him and had a child—a child who is sometimes a girl, and in other accounts, a boy.

While male monarchs throughout English history enjoyed mistresses of any number and some paraded them without fear of backlash, female monarchs have generally been held to a different standard. If Victoria were John Brown’s lover, she would have had little choice but to keep it secret. The scandal would have tarnished her monarchy, perhaps even blemishing the memory of her beloved Prince Albert.

Victoria lived for a long time after Albert’s death. No doubt she could have remarried, but a Scots commoner? Romance or not, she would have been expected to maintain a spotless veneer. While people did get tired of her wearing black and seldom appearing in public, they might have reacted very differently to evidence of a sexual affair. Rumors did abound; there was plenty of whispering and conjecture. But Victoria’s outward reputation remained unsullied. There was really no other option. She had Albert’s memory to think of, as well as her children. They, too, would have been made to suffer had their mama engaged in a love affair.

It’s often said Victoria’s personality caused the dichotomy of the era—an extremely proper surface holding people to rigid decorum, while beneath lay a seething underbelly of vice, prostitution, and the callous exploitation of women and children, which most seemed wont to ignore.

An exception was the Contagious Diseases Acts, which were enacted during Victoria’s reign. Originally an attempt to regulate prostitution and annihilate venereal disease in port towns, the Acts gave authorities license to force prostitutes into detention, where they were examined for symptoms of disease. As such things often do, the law escalated to include the entire country, including London, and became so warped that before it was repealed, any female anywhere, prostitute, housewife, or child, could be whisked into custody and forced to endure a humiliating examination. (Josephine Butler, a feminist of the times, referred to these exams as “surgical rape,” eerily reminiscent of forced, modern day, trans-vaginal ultrasounds.) Stories have come down to us of frightened women fighting the officers to no avail. The police were given sweeping powers; if their suspects refused to comply they faced imprisonment. Sometimes these women were restrained in straitjackets. Sometimes they were virgins. There are accounts of this aggression resulting in suicide.

While Queen Victoria and her daughters never had to fear being mistaken for prostitutes, few other ladies could make such a claim when the Acts were in full force. In many ways Victoria herself contributed to the problems women faced. She was adamantly against women being allowed to vote, and famously said, “Let women be what God intended, a helpmate for man, but with totally different duties and vocations.”

The Royal Commission supported this attitude with their public announcement that while men who consorted with prostitutes were merely indulging in natural impulses, the prostitutes were preying on their clients for financial gain. Such widespread beliefs supported the idea of woman as “unclean,” and encouraged the pervasive conviction that females alone caused venereal disease. Consequently, only women were arrested, tested, and if infected, forcibly confined, a remedy that would have done little to slow proliferation since men were never detained or examined.

This was Queen Victoria’s world. Small wonder that she would choose to keep her romance with her Scots servant in the background, unlike many English kings, who felt themselves above the judgment of their inferiors.

Oddly, though a woman ruled as the figurative head of the country, common women could hardly get a break. Unwed mothers in the Victorian era suffered much, up to and including death, but judgment against the fathers is remarkably absent. Today we’re seeing alarming echoes of past times in a vocal resurgence of hostility toward women for any number of things, notably their own rapes. The “unclean” notion seems to be trying to make a comeback. Across the globe, in every country, girls and women are finding that equality remains an elusive goal, and it might even be theorized that progress is slowing. Listening to what some current politicians advocate suggests we haven’t come so very far from the Victorian era. There have even been disturbing suggestions that the women’s vote should be taken away. All this makes one ponder anew the Age of Queen Victoria. Could society’s pendulum be trying to swing back toward it?

At the end of her life, Victoria asked to be buried not only with mementos of her husband, but also with a lock of John Brown’s hair, his photograph, a ring, and several of his letters. She obviously cared for this man, though we will probably never know the true extent. She lived in fascinating times, where industrial advances were exploding while human rights issues remained intractable.

Josephine Butler and the Contagious Diseases Acts make an appearance in my upcoming Victorian era novel, The Sixth Labyrinth. Before meeting Josephine, my protagonist is ignorant of the law, and of the cold facts surrounding London’s underbelly. Knowledge, coupled with Mrs. Butler’s innate strength and personality, change her profoundly.

*****

A big thanks to Rebecca Lochlann. She’ll give away a signed paperback copy of The Year-god’s Daughter to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Sunday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.