Relevant History welcomes Charlotte Milne, a naval daughter who grew up in the Scottish Borders. She worked for the Scottish National Trust, Makerere University in Uganda, and for an American software house. Although writing ‘stories’ since schooldays, she published her first novel, Dolphin Days, in 2017. Come In From the Cold (summer 2019 release), set in Scotland, tells the story of a WW2 naval officer on Russian convoys, through three generations, solving a seventy-year old murder mystery on the way. Charlotte is a keen genealogist and involved in various community-based organisations. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes Charlotte Milne, a naval daughter who grew up in the Scottish Borders. She worked for the Scottish National Trust, Makerere University in Uganda, and for an American software house. Although writing ‘stories’ since schooldays, she published her first novel, Dolphin Days, in 2017. Come In From the Cold (summer 2019 release), set in Scotland, tells the story of a WW2 naval officer on Russian convoys, through three generations, solving a seventy-year old murder mystery on the way. Charlotte is a keen genealogist and involved in various community-based organisations. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Goodreads.

*****

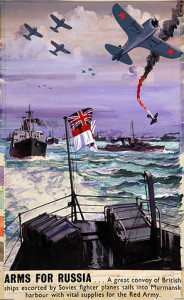

In World War 2, Roosevelt and Churchill desperately needed to prevent Russia from allying with Germany. If it did so, they knew the western allies would lose the war. In return for Russia’s alliance with the West, Stalin demanded vast amounts of food and arms for his starving and ill-equipped people. Germany and its allies blocked the land routes, so the only way to get supplies to Russia was by sea. The only ports available were within the Arctic Circle—Murmansk and Archangel—with all of Hitler’s sea and air power under orders to prevent them from reaching Russia.

In World War 2, Roosevelt and Churchill desperately needed to prevent Russia from allying with Germany. If it did so, they knew the western allies would lose the war. In return for Russia’s alliance with the West, Stalin demanded vast amounts of food and arms for his starving and ill-equipped people. Germany and its allies blocked the land routes, so the only way to get supplies to Russia was by sea. The only ports available were within the Arctic Circle—Murmansk and Archangel—with all of Hitler’s sea and air power under orders to prevent them from reaching Russia.

How did Britain and the US get supplies to Russia?

Merchant ships gathered in a deep-water anchorage in the west of Scotland called Loch Ewe. Protected by escorts of heavily-armed allied warships, they joined up with other merchant ships in Iceland, and headed, nervously, towards Russia’s only two northern open-water ports.

Merchant ships gathered in a deep-water anchorage in the west of Scotland called Loch Ewe. Protected by escorts of heavily-armed allied warships, they joined up with other merchant ships in Iceland, and headed, nervously, towards Russia’s only two northern open-water ports.

On the way, the Luftwaffe, based in occupied Norway, would bomb the ships from the air, U-boat submarines lurking beneath the White Sea would attack with torpedoes, and their fast and mighty warships could outgun the Western allies.

We think these days that communication is so simple! Hard to remember that there was no internet, no satellites, and radar was a new technology. Radio silence was kept, to obscure the convoy’s position. Ship to ship communication was by visual signal only.

The weather was a worse enemy. In summer there was 24-hour daylight—enemy aircraft, ships and submarines worked round the clock too. Summer convoys became so dangerous they had to be discontinued. In winter there was 24-hour darkness, the sea froze and the ice sheet grew rapidly from north to south. This meant that convoys had to sail much further south and were then squeezed between the ice and the land mass to the south. Much easier for the Germans to find and attack them.

Winter storms were indescribable. The winter water temperature often dropped to minus 2 degrees Celsius, air temperature down to minus 22 degrees Celsius, without taking wind into account. Waves were often 40 to 50 feet high, visibility was nil in driving snow and spray, ships came near the vertical both going up and coming down the waves, they crashed and bounced and wallowed and capsized. Capsizing was one of the greatest dangers due to the weight of ice which accumulated above decks from the water flooding the superstructure of ships. Ice accumulated on guns, turrets and shells; masts, rigging, funnels, pipes and guard rails; on containers, aircraft, tanks and munitions stacked on decks, the decks themselves were like ice rinks, doors sealed themselves, ropes, anchors, fenders became as hard as iron and as immoveable. Clothes were inadequate—no ski jackets or cold weather gear as we know it. Crews had to spend hours on deck, tossed about like dolls, chipping at the ice and throwing it overboard, just so that the ship would not turn turtle. Fuel and oil coagulated in the low temperatures. Unimaginable conditions. Unimaginably brave men.

Winter storms were indescribable. The winter water temperature often dropped to minus 2 degrees Celsius, air temperature down to minus 22 degrees Celsius, without taking wind into account. Waves were often 40 to 50 feet high, visibility was nil in driving snow and spray, ships came near the vertical both going up and coming down the waves, they crashed and bounced and wallowed and capsized. Capsizing was one of the greatest dangers due to the weight of ice which accumulated above decks from the water flooding the superstructure of ships. Ice accumulated on guns, turrets and shells; masts, rigging, funnels, pipes and guard rails; on containers, aircraft, tanks and munitions stacked on decks, the decks themselves were like ice rinks, doors sealed themselves, ropes, anchors, fenders became as hard as iron and as immoveable. Clothes were inadequate—no ski jackets or cold weather gear as we know it. Crews had to spend hours on deck, tossed about like dolls, chipping at the ice and throwing it overboard, just so that the ship would not turn turtle. Fuel and oil coagulated in the low temperatures. Unimaginable conditions. Unimaginably brave men.

The convoys drained the British war effort. Every escorting warship was a ship which could have been fighting elsewhere on the warfront. Churchill became extremely unpopular for supplying Russia.

In total, 104 Allied merchant ships and 18 warships were sunk on the Arctic convoys. 829 merchant mariners and 1,944 navy personnel were killed. Killed by guns, torpedoes, sinking, drowning, fire, hypothermia, inhalation of oil and Russian hospitals.

What happened when ships arrived in Russia?

Both Archangel in the White Sea and Murmansk in the Kola Inlet were very basic fishing ports. Wooden quays, virtually no lifting gear, wooden sheds, no hotels or shops of any kind. The officials were deeply suspicious of the capitalists bringing ships and goods into their country. These ports were so far from central government that orders seldom got to them. There was no infrastructure or telephones, and in winter, they were totally isolated. Murmansk was very close to German airfields in Norway, and many ships were bombed lying alongside. Ships companies were not allowed ashore—there was nothing to go ashore for! They were not allowed to use their own boats, even to visit their own ships. Russian guards were posted at every gangplank, bureaucracy was rampant and corrupt, and few Russians were able to speak English or could read or write.

Goods were mainly unloaded by hand by what appeared to be slave labour—serfs—and seldom found their way to the right destination, food supplies for the starving citizens often lying rotting on the quays. Tanks, guns, crated aircraft, munitions—no-one seemed to know who or where they were destined for, nor did anyone seem to care. Many sailors arrived with terrible injuries after German attacks, but the ‘hospital’ was so basic, with no hygiene, facilities or medications, that many died needlessly in ghastly conditions. Western medical supplies were turned away. Many of the RAF planes which should have been protecting Murmansk and attacking German airfields were grounded, but the spare parts brought on the convoys were not allowed to be delivered and were impounded or stolen along with vast amounts of vital war supplies.

The bureaucracy surrounding every movement of every man and every ship, every container and every item transported was such that sometimes it took weeks or months to offload vital supplies for the Russian front line, trapping the escorts in port. Ships were prevented from refuelling, or taking on water or food supplies, their crews virtually starving, despite bringing hundreds of tons of foodstuffs into the country. Stalin might have been an official ally, but for the Arctic convoys, Russia certainly didn’t behave like one.

The story of the Road to Russia and the sacrifice and bravery of those seamen remained almost unknown under The Official Secrets Act. Until 1999 there was no memorial, and no medal was awarded until 2013.

*****

A big thanks to Charlotte Milne! She’ll give away one £5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog this week as well as one $5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the United States or Canada who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Charlotte Milne! She’ll give away one £5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog this week as well as one $5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the United States or Canada who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day.

Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day. A big thanks to Renée Dahlia!

A big thanks to Renée Dahlia! Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Chrissie Parker, who writes for the Zakynthos Informer and has written for other publications including The Bristolian, The Huffington Post, Ancient Egypt and The Artist Unleashed. Among the Olive Groves won a Historical Fiction Award in 2016. In 2013 her poem “Maisie” was performed at Bath International Literary Festival’s event “100 poems by 100 women.” Chrissie’s love of history and travel is the inspiration for her books. She has completed two Egyptology courses and an Archaeology course with Exeter University. She is currently working on a follow-up to Among the Olive Groves and a co-authored history book about Zakynthos. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Chrissie Parker, who writes for the Zakynthos Informer and has written for other publications including The Bristolian, The Huffington Post, Ancient Egypt and The Artist Unleashed. Among the Olive Groves won a Historical Fiction Award in 2016. In 2013 her poem “Maisie” was performed at Bath International Literary Festival’s event “100 poems by 100 women.” Chrissie’s love of history and travel is the inspiration for her books. She has completed two Egyptology courses and an Archaeology course with Exeter University. She is currently working on a follow-up to Among the Olive Groves and a co-authored history book about Zakynthos. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  When mainland Greece was invaded in 1941 during World War II, life for the Greek population was hard. Initially they were under Italian rule, part of the Axis powers. On 9 September 1943, the small Greek island of Zakynthos, situated in the Ionian Sea, fell under German rule. Despite the hardship of war, Zakynthos would leave Greece with a lasting tale of extreme bravery.

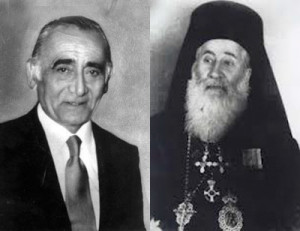

When mainland Greece was invaded in 1941 during World War II, life for the Greek population was hard. Initially they were under Italian rule, part of the Axis powers. On 9 September 1943, the small Greek island of Zakynthos, situated in the Ionian Sea, fell under German rule. Despite the hardship of war, Zakynthos would leave Greece with a lasting tale of extreme bravery. Mayor Karrer shared his concerns with the island’s bishop, Chrysostomos, who months before had been a prisoner of the Germans and not long released back to the island. The Bishop visited Berenz who confirmed the request. Berenz also told Chrysostomos that the Jewish population was to be arrested. It’s said that in his shock the Bishop responded that the Jewish residents of Zakynthos were “obedient, good subjects of Greece, who were hard-working and peace loving. They were non-dangerous citizens of Zakynthos who were part of his flock.” The two men argued with weapon and staff drawn and in the end required an intervention by a German Captain, Alfredo Litt. Captain Litt explained to Chrysostomos that they had orders, and the Bishop couldn’t refuse them. After much discussion, Litt and Chrysostomos agreed to meet a few days later to discuss the issue further.

Mayor Karrer shared his concerns with the island’s bishop, Chrysostomos, who months before had been a prisoner of the Germans and not long released back to the island. The Bishop visited Berenz who confirmed the request. Berenz also told Chrysostomos that the Jewish population was to be arrested. It’s said that in his shock the Bishop responded that the Jewish residents of Zakynthos were “obedient, good subjects of Greece, who were hard-working and peace loving. They were non-dangerous citizens of Zakynthos who were part of his flock.” The two men argued with weapon and staff drawn and in the end required an intervention by a German Captain, Alfredo Litt. Captain Litt explained to Chrysostomos that they had orders, and the Bishop couldn’t refuse them. After much discussion, Litt and Chrysostomos agreed to meet a few days later to discuss the issue further. A lasting memorial to both Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos stands on the original site of the Zakynthian Jewish Synagogue, destroyed in the Great Ionian Earthquake of 1953. This important memorial marks the incredible heroism of both men, and the story of their bravery lives on in the hearts and minds of the Zakynthian people.

A lasting memorial to both Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos stands on the original site of the Zakynthian Jewish Synagogue, destroyed in the Great Ionian Earthquake of 1953. This important memorial marks the incredible heroism of both men, and the story of their bravery lives on in the hearts and minds of the Zakynthian people. A big thanks to Chrissie Parker! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Among the Olive Groves to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide, in all electronic versions except PDF.

A big thanks to Chrissie Parker! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Among the Olive Groves to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide, in all electronic versions except PDF. Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet.

In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet. A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about

A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about  Relevant History welcomes Emma Rose Millar, who writes historical fiction and children’s picture books. She won the Legend category of the Chaucer Awards for Historical Fiction with Five Guns Blazing in 2014. Her novella The Women Friends: Selina, based on the work of Gustav Klimt and co-written with author Miriam Drori, was published in 2016 by Crooked Cat Books and was shortlisted for the Goethe Award for Late Historical Fiction. Her third novel, Delirium, a Victorian ghost story published by Crooked Cat Books, was shortlisted for the Chanticleer Paranormal Book Awards in 2017. Emma’s historical poems for children are published by The Emma Press. To learn more about her and her books, follow her on

Relevant History welcomes Emma Rose Millar, who writes historical fiction and children’s picture books. She won the Legend category of the Chaucer Awards for Historical Fiction with Five Guns Blazing in 2014. Her novella The Women Friends: Selina, based on the work of Gustav Klimt and co-written with author Miriam Drori, was published in 2016 by Crooked Cat Books and was shortlisted for the Goethe Award for Late Historical Fiction. Her third novel, Delirium, a Victorian ghost story published by Crooked Cat Books, was shortlisted for the Chanticleer Paranormal Book Awards in 2017. Emma’s historical poems for children are published by The Emma Press. To learn more about her and her books, follow her on  Worked to the bone, starved, beaten, and abused: this was the fate of some 30,000 women whose care was entrusted to nuns in Ireland’s Magdalene Asylums, also known as Magdalene Laundries. These institutions were set up during the eighteenth-century to house prostitutes—so-called “fallen women”—but quickly became places of unknown cruelty and hardship, where any women and girls as young as nine, branded as “undesirable” by the Church, could be incarcerated. For over two hundred years, unmarried mothers, women deemed “promiscuous,” or those who defied their husbands or fathers could find themselves locked up in one of the asylums. Others had learning difficulties or had been the victims of rape or sexual assault. Some were sent there simply for being “too pretty.” Once there, they were starved, beaten, and forced into backbreaking work in the asylum laundries. Babies were usually taken away from their mothers and offered up for adoption.

Worked to the bone, starved, beaten, and abused: this was the fate of some 30,000 women whose care was entrusted to nuns in Ireland’s Magdalene Asylums, also known as Magdalene Laundries. These institutions were set up during the eighteenth-century to house prostitutes—so-called “fallen women”—but quickly became places of unknown cruelty and hardship, where any women and girls as young as nine, branded as “undesirable” by the Church, could be incarcerated. For over two hundred years, unmarried mothers, women deemed “promiscuous,” or those who defied their husbands or fathers could find themselves locked up in one of the asylums. Others had learning difficulties or had been the victims of rape or sexual assault. Some were sent there simply for being “too pretty.” Once there, they were starved, beaten, and forced into backbreaking work in the asylum laundries. Babies were usually taken away from their mothers and offered up for adoption. It was not until the discovery of a mass grave at Our Lady of Charity Convent in Dublin that the media became involved and printed articles questioning goings-on at the asylums. One hundred and fifty-five bodies were found in the grave, but only seventy-five death certificates had been issued. The nuns claimed there had been an administrative error, but there was a public outcry, and ultimately the United Nations called for a public enquiry. Suddenly, women began perusing cases for violations against Human Rights and making disclosures about the abuse they had suffered.

It was not until the discovery of a mass grave at Our Lady of Charity Convent in Dublin that the media became involved and printed articles questioning goings-on at the asylums. One hundred and fifty-five bodies were found in the grave, but only seventy-five death certificates had been issued. The nuns claimed there had been an administrative error, but there was a public outcry, and ultimately the United Nations called for a public enquiry. Suddenly, women began perusing cases for violations against Human Rights and making disclosures about the abuse they had suffered. A big thanks to Emma Rose Millar! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Delirium to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.K. only.

A big thanks to Emma Rose Millar! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Delirium to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.K. only. Happy New Year! Relevant History welcomes Karen Wills, who lives near Glacier National Park. She writes historical, often frontier, novels. She’s practiced law, representing plaintiffs in Civil Rights cases. She’s taught English classes at college and secondary public school levels, including on South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation and in the Inupiaq village of Wales, Alaska. She’s encountered both grizzly and polar bears and still believes we need wild creatures and wilderness. Her novels include the self-published archaeological thriller Remarkable Silence and traditionally published River with No Bridge. All Too Human will be released in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Happy New Year! Relevant History welcomes Karen Wills, who lives near Glacier National Park. She writes historical, often frontier, novels. She’s practiced law, representing plaintiffs in Civil Rights cases. She’s taught English classes at college and secondary public school levels, including on South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation and in the Inupiaq village of Wales, Alaska. She’s encountered both grizzly and polar bears and still believes we need wild creatures and wilderness. Her novels include the self-published archaeological thriller Remarkable Silence and traditionally published River with No Bridge. All Too Human will be released in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  Fery, born Johann Nepomuck Levy in Strasswatchen, Austria, on 25 March 1859, moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1883, changing his name to John Fery. An outdoorsman, he frequently left his family in Milwaukee to go west to paint. Hill noticed his work and hired him for the “See America First” campaign. Prolific, Fery created big mountainous scenes for the Great Northern that hung in Glacier National Park hotels, Great Northern depots, and ticket agent offices. Fery produced about fourteen huge landscapes per month.

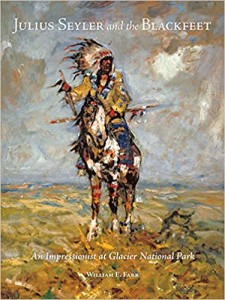

Fery, born Johann Nepomuck Levy in Strasswatchen, Austria, on 25 March 1859, moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1883, changing his name to John Fery. An outdoorsman, he frequently left his family in Milwaukee to go west to paint. Hill noticed his work and hired him for the “See America First” campaign. Prolific, Fery created big mountainous scenes for the Great Northern that hung in Glacier National Park hotels, Great Northern depots, and ticket agent offices. Fery produced about fourteen huge landscapes per month. Julius Seyler was born in Munich, Germany, in 1873. He studied art but also became a competitive ice skater. He achieved fame for both his impressionist art and prowess at speed skating before he came to America.

Julius Seyler was born in Munich, Germany, in 1873. He studied art but also became a competitive ice skater. He achieved fame for both his impressionist art and prowess at speed skating before he came to America. Our third artist, Winold Reiss, was born in Karlsrhuh, Germany, in the Black Forest region, in 1888. He sailed to America in 1913 eager to paint Indians, eventually finding his way to Glacier National Park. While Julius Seyler painted iconic Native American types, Reiss focused in detail on Blackfeet individuals, their features and clothing. His realism appealed to Hill. Reiss’s work, starting in 1933, appeared on calendars and even menus for the Great Northern Railway.

Our third artist, Winold Reiss, was born in Karlsrhuh, Germany, in the Black Forest region, in 1888. He sailed to America in 1913 eager to paint Indians, eventually finding his way to Glacier National Park. While Julius Seyler painted iconic Native American types, Reiss focused in detail on Blackfeet individuals, their features and clothing. His realism appealed to Hill. Reiss’s work, starting in 1933, appeared on calendars and even menus for the Great Northern Railway. A big thanks to Karen Wills! She’ll give away a hardback copy of River with No Bridge to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Karen Wills! She’ll give away a hardback copy of River with No Bridge to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.