Joel Lane Museum House director Lanie Hubbard shows how a group of enslaved people from late 18th-century North Carolina was recently memorialized.

###

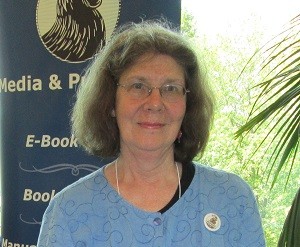

Relevant History welcomes Lanie Hubbard, director of the Joel Lane Museum House (JLMH) in Raleigh, North Carolina. A native of Arizona, Lanie’s background for the position is unorthodox. An MA in literature honed her research and storytelling skills; and she spent four New Mexico summers in historic costume, teaching Boy Scouts to blacksmith and apply cattle brands to their hiking boots, while keeping the kids from getting themselves eaten by bears. Blacksmithing and boot-ruining taught Lanie to love sharing history, while camp oversight and bear-disappointment prepared her for management. After joining JLMH as a part-time docent in 2014, she became director in 2017. To learn more, follow JLMH on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes Lanie Hubbard, director of the Joel Lane Museum House (JLMH) in Raleigh, North Carolina. A native of Arizona, Lanie’s background for the position is unorthodox. An MA in literature honed her research and storytelling skills; and she spent four New Mexico summers in historic costume, teaching Boy Scouts to blacksmith and apply cattle brands to their hiking boots, while keeping the kids from getting themselves eaten by bears. Blacksmithing and boot-ruining taught Lanie to love sharing history, while camp oversight and bear-disappointment prepared her for management. After joining JLMH as a part-time docent in 2014, she became director in 2017. To learn more, follow JLMH on Facebook.

*****

On Sunday 16 February 2020, dozens of members of the Raleigh community gathered at the JLMH to dedicate a new memorial to forty-three men, women, and children enslaved by Joel Lane and his family. We talked about the history, spoke the names, and prayed. Likely descendants of the enslaved lifted the cloth, revealing the new monument. We sang “Amazing Grace.” It was a profound experience. (Check out the news story posted a few days before the ceremony.)

This site was the seat of a large plantation founded in 1769. We speak of Joel Lane as a local founding father. If we are to fully explore the history of this place and Lane’s role in founding Wake County, Raleigh, and America, we must discuss human bondage.

The memorial, cast in bronze and mounted to the granite pillar supporting the sundial in our Herb Garden, bears the name of each enslaved person our researchers have identified. For the first time, permanently installed on the grounds of Joel Lane’s former plantation, stands a physical tribute to those whose lives and labor were twisted into the warp and weave of life in this place, whose hands laid the literal foundations. The new plaque reflects a history that is factually inseparable from the other stories of our beginnings.

The memorial, cast in bronze and mounted to the granite pillar supporting the sundial in our Herb Garden, bears the name of each enslaved person our researchers have identified. For the first time, permanently installed on the grounds of Joel Lane’s former plantation, stands a physical tribute to those whose lives and labor were twisted into the warp and weave of life in this place, whose hands laid the literal foundations. The new plaque reflects a history that is factually inseparable from the other stories of our beginnings.

It also stands in memory of Florence Mitchell, longtime docent and education chair. She made a mission of researching the people enslaved by Joel Lane and added greatly to our knowledge. Florence left a generous 2018 bequest to the museum. This permanent memorial to the enslaved, made possible by that gift, honors her work and continues it.

It also stands in memory of Florence Mitchell, longtime docent and education chair. She made a mission of researching the people enslaved by Joel Lane and added greatly to our knowledge. Florence left a generous 2018 bequest to the museum. This permanent memorial to the enslaved, made possible by that gift, honors her work and continues it.

As we began the project, space was limited. JLMH stands on about a third of an acre—land already occupied by four structures, a formal garden, and an herb garden. It was in the herb garden that we found our solution: a sundial that never quite fit in. We would turn a distraction into a teaching tool. We seem to do that a lot.

Embracing anachronism

Lately, I’ve been teaching every third grader who crosses our threshold the word anachronism. It’s our docents’ delightful job to dress up in colonial clothing and physically guide the children into the foreign world of the eighteenth century, while gently reminding them not to touch the teacups. It’s every eight-year-old’s job, contractually, to point out a smoke detector and demand, “okay, so what’s that?”—then use the distraction to reach for the forbidden teacups.

Children use the tools we give them. When I give them the word anachronism, they can contextualize not only the smoke detector, but my strange period costume. In their electrical-digital world, my apron and cap set me outside of their time—but in my world, they’re the visitors, with a tourist’s eagerness to explore. I introduce myself as anachronism, then lead them to a place where they become anachronism. That smoke detector, then, isn’t a glitch they can exploit to confuse me—it’s simply an anachronism, much less interesting than the teacup I’m showing them. This strategy lets me teach them not only the local history but a wider, conceptual notion of History. Anachronism gives us context to move past the little modern distractions to compare and contrast eras, discuss how people solved problems in the past, and find, through difference, the similarities people share across time.

The sundial

It all works until the tour reaches the sundial, which manages to disrupt tours like—well, like clockwork. By the time a class makes it to the herb garden, their docent has already shepherded them through myriad more obvious distractions. The nearby train whistle. A chaperone’s cell phone ringer. That neighbor with a big yellow hat and a bushy beard who rides a bicycle lifted like a monster truck. A squirrel.

The sundial is a circle of green-patinaed bronze, mounted on a grey, rough-hewn granite block, still marked from the quarry. Green on grey stone, in a garden of green herbs and grey gravel. It’s the sort of ornament one expects in a historical garden. Adults tend not to notice it.

The sundial is a circle of green-patinaed bronze, mounted on a grey, rough-hewn granite block, still marked from the quarry. Green on grey stone, in a garden of green herbs and grey gravel. It’s the sort of ornament one expects in a historical garden. Adults tend not to notice it.

It’s all third-graders can see. Children flock to the sundial. “What is that?” “Is everyone late when it rains?” “What about Daylight Savings?” “Isn’t it better to have a clock indoors?” “How do they wake up if it doesn’t have an alarm?”

This is supposed to be the part of the tour where we talk about herbs. Yarrow to stop bleeding. Tansy to repel flies and as yellow dye. Rosemary for remembrance. Lamb’s ear as top-shelf colonial-era toilet paper. Medicines, flavors, chemicals, symbols; see and touch and smell. The sundial, in comparison, doesn’t offer much. It’s a technology that had existed millennia before Joel Lane’s time, but an object no more important to everyday life in the eighteenth century than to the twenty-first. (Clocks existed!) It is doubly anachronistic—unfamiliar to the children, but irrelevant to the tour.

Thus a longstanding problem became our solution, centered in a place of peace and honor, surrounded by fruits of the sorts of labor the enslaved were made to perform. We mounted the plaque on the northern face. The homes of the enslaved were probably to the north. North for hope, for freedom. North, toward an end to slavery. The once-distracting sundial will now begin a new conversation, about the most troubling anachronism of all: slavery.

Slavery has been integral to JLMH interpretation since before my time as director. It’s a troubling subject that rightfully pulls joy from docent and guests alike—it makes people sad and angry. It can be difficult to explain to children. They innately understand the unfairness and wrongness of it, but not how people could justify doing such a thing. They’ve learned of Joel Lane as a founding father, but can someone whose accomplishments relied on enslaved labor be a great man? Can he be good? These are the questions a docent doesn’t answer. We just help kids ask them. The new memorial honors the enslaved and supports this work.

*****

A big thanks to Lanie Hubbard! She’ll give away a copy of The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, an autobiography of the son of one of Joel Lane’s slaves; plus a set of four tour tickets to the Joel Lane Museum House (no expiration date), to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Lanie Hubbard! She’ll give away a copy of The Narrative of Lunsford Lane, an autobiography of the son of one of Joel Lane’s slaves; plus a set of four tour tickets to the Joel Lane Museum House (no expiration date), to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Join Suzanne Adair’s Patreon, and subscribe to her free newsletter.

Relevant History welcomes back Ana Brazil, a longtime student of history and a voracious reader of mystery. Her historical mystery novel and short stories feature brash American heroines, the more bodacious the better. Ana’s debut novel, Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, won the 2018 IBPA GOLD Medal for Historical Fiction. Her current work-in-progress features a vaudevillian-chanteuse-who-knows-too-much set in 1919 San Francisco. Ana is an active member of Sisters in Crime and the Historical Novel Society, and a founding member of the

Relevant History welcomes back Ana Brazil, a longtime student of history and a voracious reader of mystery. Her historical mystery novel and short stories feature brash American heroines, the more bodacious the better. Ana’s debut novel, Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, won the 2018 IBPA GOLD Medal for Historical Fiction. Her current work-in-progress features a vaudevillian-chanteuse-who-knows-too-much set in 1919 San Francisco. Ana is an active member of Sisters in Crime and the Historical Novel Society, and a founding member of the

Fortunately for all, the Golden Age of postcards intersected with the turn-of-the-century City Beautiful movement (a concerted effort to enhance the appearance of American towns and cities) and with the advent of automobile-inspired tourism. As a result, postcards of the Golden Age showed off the best and brightest of a city’s civic buildings, parks, churches, residences, and commercial areas. And don’t forget the cemeteries! I’ve collected countless postcards of New Orleans’ lushly landscaped Metairie and St. Louis cemeteries.

Fortunately for all, the Golden Age of postcards intersected with the turn-of-the-century City Beautiful movement (a concerted effort to enhance the appearance of American towns and cities) and with the advent of automobile-inspired tourism. As a result, postcards of the Golden Age showed off the best and brightest of a city’s civic buildings, parks, churches, residences, and commercial areas. And don’t forget the cemeteries! I’ve collected countless postcards of New Orleans’ lushly landscaped Metairie and St. Louis cemeteries. Bird’s eye postcards—just like the bird’s eye maps that inspired them—provide an overview of all or parts of the city.

Bird’s eye postcards—just like the bird’s eye maps that inspired them—provide an overview of all or parts of the city. Streetscapes give you an idea of a manageable landscape, including these Italian Headquarters.

Streetscapes give you an idea of a manageable landscape, including these Italian Headquarters. Blocks & Buildings. New Orleans has always been renowned for glorious residences (like this one on Esplanade Avenue), many of which were built on entire city blocks.

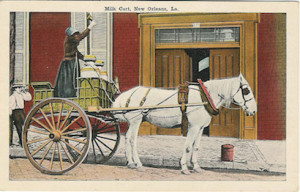

Blocks & Buildings. New Orleans has always been renowned for glorious residences (like this one on Esplanade Avenue), many of which were built on entire city blocks. People, Places, & Things—I’ve always wanted to put this milk seller (and the carefree boy in the boater leaning against an electrical pole) into one of my stories, but just haven’t found the right place for either of them yet.

People, Places, & Things—I’ve always wanted to put this milk seller (and the carefree boy in the boater leaning against an electrical pole) into one of my stories, but just haven’t found the right place for either of them yet. A big thanks to Ana Brazil! She’ll give away a packet of four reproduction postcards and one original postcard of Italian Headquarters, plus a paperback copy of Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week (available Tuesday 4 February). I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the US only.

A big thanks to Ana Brazil! She’ll give away a packet of four reproduction postcards and one original postcard of Italian Headquarters, plus a paperback copy of Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week (available Tuesday 4 February). I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the US only. Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Karen Perkins, author of the Yorkshire Ghost Stories, the Pendle Witch Short Stories, and the Valkyrie Series of historical nautical fiction. All of her fiction has appeared at the top of bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic, including the top 21 in the UK Kindle Store in 2018. To learn more about Karen and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Karen Perkins, author of the Yorkshire Ghost Stories, the Pendle Witch Short Stories, and the Valkyrie Series of historical nautical fiction. All of her fiction has appeared at the top of bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic, including the top 21 in the UK Kindle Store in 2018. To learn more about Karen and her books, visit her  The horror of the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts in 1692 is well known, especially as it involved children as accusers leading to trials and executions. But did you know that a similar scenario played out eighty years before in the north of England?

The horror of the Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts in 1692 is well known, especially as it involved children as accusers leading to trials and executions. But did you know that a similar scenario played out eighty years before in the north of England? The answer may well lie in Lancashire, England, wherein lies Pendle Forest. Within this area, in the shadow of the ominously looming Pendle Hill, lay a humble abode with the rather grand name of Malkin Towers. Although the witch trials sucked in many women from the surrounding countryside, this was the hub of the Pendle Witch Hunts, which led to trials at the ancient Lancaster and York Castles.

The answer may well lie in Lancashire, England, wherein lies Pendle Forest. Within this area, in the shadow of the ominously looming Pendle Hill, lay a humble abode with the rather grand name of Malkin Towers. Although the witch trials sucked in many women from the surrounding countryside, this was the hub of the Pendle Witch Hunts, which led to trials at the ancient Lancaster and York Castles. Growing up not far away in the Yorkshire Dales, I had long known of the “Pendle Witches.” I wanted to find out more and understand how and why the witch trials had happened at all, and was determined to write about them. I had already written one book set in Haworth, the home village of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë (Parliament of Rooks), and as Haworth is literally over the hill from Pendle (Cathy and Heathcliff may well have been able to see Pendle Hill from Wuthering Heights), the Pendle witch trials became the inspiration for my second (and forthcoming) Ghosts of Haworth novel, A Question of Witchcraft.

Growing up not far away in the Yorkshire Dales, I had long known of the “Pendle Witches.” I wanted to find out more and understand how and why the witch trials had happened at all, and was determined to write about them. I had already written one book set in Haworth, the home village of Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë (Parliament of Rooks), and as Haworth is literally over the hill from Pendle (Cathy and Heathcliff may well have been able to see Pendle Hill from Wuthering Heights), the Pendle witch trials became the inspiration for my second (and forthcoming) Ghosts of Haworth novel, A Question of Witchcraft. In England, King Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church to set up the Church of England. Then the country swayed brutally back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism with successive monarchs, plus a Puritan parliament during the English Civil War in the mid-1600s. No wonder people were keen to brave the dangers of a six-week ocean voyage aboard the Mayflower and similar ships for the freedom to practice their religion without persecution in Massachusetts Bay!

In England, King Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church to set up the Church of England. Then the country swayed brutally back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism with successive monarchs, plus a Puritan parliament during the English Civil War in the mid-1600s. No wonder people were keen to brave the dangers of a six-week ocean voyage aboard the Mayflower and similar ships for the freedom to practice their religion without persecution in Massachusetts Bay! A big thanks to Karen Perkins! She’ll give away either a Kindle ebook or Audible audiobook of her historical fiction short story, Murder by Witchcraft, to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Karen Perkins! She’ll give away either a Kindle ebook or Audible audiobook of her historical fiction short story, Murder by Witchcraft, to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

Relevant History welcomes back historical mystery author Anne Louise Bannon, who writes the “Old Los Angeles” mystery series set in the 1870s and featuring Maddie Wilcox, and the “Freddie and Kathy Roaring ‘20s” series featuring Freddie Little and Kathy Briscow. Her most recent title is Death of the City Marshal. She and her husband live in Southern California with an assortment of critters. To learn more about Anne and her books, visit her

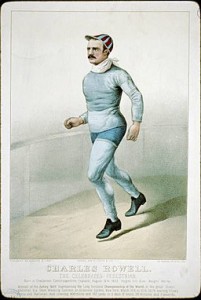

Relevant History welcomes back historical mystery author Anne Louise Bannon, who writes the “Old Los Angeles” mystery series set in the 1870s and featuring Maddie Wilcox, and the “Freddie and Kathy Roaring ‘20s” series featuring Freddie Little and Kathy Briscow. Her most recent title is Death of the City Marshal. She and her husband live in Southern California with an assortment of critters. To learn more about Anne and her books, visit her  By the fall of 1870, the police force had been expanded to six men. No surprise, the single most common petition made to the Common Council (as it was known at the time) was to request more police officers. The population had grown to around 5,700, still mostly men. Murders were down, but not by much, and one of the guys doing a fair amount of the killing was none other than City Marshal Warren. The other guy was probably Deputy Joseph Dye.

By the fall of 1870, the police force had been expanded to six men. No surprise, the single most common petition made to the Common Council (as it was known at the time) was to request more police officers. The population had grown to around 5,700, still mostly men. Murders were down, but not by much, and one of the guys doing a fair amount of the killing was none other than City Marshal Warren. The other guy was probably Deputy Joseph Dye. A big thanks to Anne Louise Bannon! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Death of the City Marshal to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Anne Louise Bannon! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Death of the City Marshal to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes back nonfiction author Kimberly K. Walters, who started reenacting as a hearth cook in 2009 as the Washington Headquarters housekeeper, modeled after Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson. A Book of Cookery by a Lady (2014) is a tribute to Mrs. Thompson. An avid horse woman, animal lover, and historian, Kim is a member of the Fincastle Chapter, the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution in Kentucky. At K. Walters at the Sign of the Gray Horse, she sells reproduction and historically inspired jewelry to care for her rescued and Colonial Williamsburg retired horses. Tea in 18th Century America was released on 17 July 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

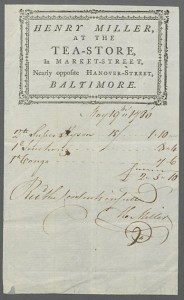

Relevant History welcomes back nonfiction author Kimberly K. Walters, who started reenacting as a hearth cook in 2009 as the Washington Headquarters housekeeper, modeled after Mrs. Elizabeth Thompson. A Book of Cookery by a Lady (2014) is a tribute to Mrs. Thompson. An avid horse woman, animal lover, and historian, Kim is a member of the Fincastle Chapter, the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution in Kentucky. At K. Walters at the Sign of the Gray Horse, she sells reproduction and historically inspired jewelry to care for her rescued and Colonial Williamsburg retired horses. Tea in 18th Century America was released on 17 July 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  In America, tea was much more than just a drink, and the book gives the reader insight into the importance of tea in the Colonies and early Federal eras. The book begins with an introduction to the history of tea, its journey to the shores of America tracing its ebbs and flows in popularity, and the cultural meaning attached to its use. Then, while giving credit to the research done by Rodris Roth, I added extensive research utilizing period newspapers, historic texts, period portraits, and prints to immerse the reader in their world.

In America, tea was much more than just a drink, and the book gives the reader insight into the importance of tea in the Colonies and early Federal eras. The book begins with an introduction to the history of tea, its journey to the shores of America tracing its ebbs and flows in popularity, and the cultural meaning attached to its use. Then, while giving credit to the research done by Rodris Roth, I added extensive research utilizing period newspapers, historic texts, period portraits, and prints to immerse the reader in their world. Tea in pre- and post-revolutionary America was a symbol of tyranny or patriotism and helped create an American identity. At first, I did not want to go in-depth on the explanation of the legal acts and taxes on commodities that set the stage for Americans’ outrage over the monopoly held by the East India Tea Company on tea. However, I felt it an essential and necessary part of this story. The acts and taxes led to the drop in popularity of tea as revolutionary sentiments grew. To drink tea became a political act, although that seemed only to be the case for imported tea. The tea ceremony was still being practiced, albeit with herbal tea as a substitute. Also tea was still being ordered for import, but we do not know if it ever made it to those who ordered it.

Tea in pre- and post-revolutionary America was a symbol of tyranny or patriotism and helped create an American identity. At first, I did not want to go in-depth on the explanation of the legal acts and taxes on commodities that set the stage for Americans’ outrage over the monopoly held by the East India Tea Company on tea. However, I felt it an essential and necessary part of this story. The acts and taxes led to the drop in popularity of tea as revolutionary sentiments grew. To drink tea became a political act, although that seemed only to be the case for imported tea. The tea ceremony was still being practiced, albeit with herbal tea as a substitute. Also tea was still being ordered for import, but we do not know if it ever made it to those who ordered it. A big thanks to Kimberly Walters! She’ll give away one hardcover copy of Tea in 18th Century America to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Kimberly Walters! She’ll give away one hardcover copy of Tea in 18th Century America to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes William Denton: historian, author, and blogger. Born and raised in Eastern North Carolina, his areas of study include ancient and classical history, North Carolina history, education, and politics. William attended North Carolina State University, Liberty University, and Unicaf University, holds a BS in Religion, an MA in History, and a Ph.D. in Humanities. He is a member of the American Historical Association and the Association of Ancient Historians. His historical nonfiction, A History of Eastern North Carolina: Indigenous People, Colonization, and the Birth of a State, will be released next week on 28 October. William and his wife live in Nash County, North Carolina with their son. To learn more about him and his books, visit his

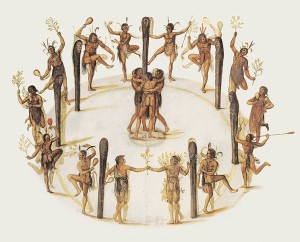

Relevant History welcomes William Denton: historian, author, and blogger. Born and raised in Eastern North Carolina, his areas of study include ancient and classical history, North Carolina history, education, and politics. William attended North Carolina State University, Liberty University, and Unicaf University, holds a BS in Religion, an MA in History, and a Ph.D. in Humanities. He is a member of the American Historical Association and the Association of Ancient Historians. His historical nonfiction, A History of Eastern North Carolina: Indigenous People, Colonization, and the Birth of a State, will be released next week on 28 October. William and his wife live in Nash County, North Carolina with their son. To learn more about him and his books, visit his  The coast of Eastern North Carolina was once home to an abundance of Algonquian tribes. The Iroquoian Tuscarora tribes were more influential within the Upper and Lower Inner Banks and Coastal Plain regions. These various Algonquian-speaking peoples occasionally formed loose affiliations and alliances, which, when paired with their overlapping cultural practices, sometimes blurred the lines of individual tribal identification.

The coast of Eastern North Carolina was once home to an abundance of Algonquian tribes. The Iroquoian Tuscarora tribes were more influential within the Upper and Lower Inner Banks and Coastal Plain regions. These various Algonquian-speaking peoples occasionally formed loose affiliations and alliances, which, when paired with their overlapping cultural practices, sometimes blurred the lines of individual tribal identification. While the exact power structure varied from tribe-to-tribe, all Algonquian tribes shared common elements and traits. For example, unlike their Iroquoian counterparts, the Algonquians did not form strong alliances or political bonds with other Algonquian tribes, though they did collectively respond to military threats at times. The Algonquians were more interested in village-based relationships, with many clans who claimed a common ancestry gathering together in a local settlement.

While the exact power structure varied from tribe-to-tribe, all Algonquian tribes shared common elements and traits. For example, unlike their Iroquoian counterparts, the Algonquians did not form strong alliances or political bonds with other Algonquian tribes, though they did collectively respond to military threats at times. The Algonquians were more interested in village-based relationships, with many clans who claimed a common ancestry gathering together in a local settlement. A big thanks to William Denton! He’ll give away a copy of A History of Eastern North Carolina to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

A big thanks to William Denton! He’ll give away a copy of A History of Eastern North Carolina to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only. Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native Jeri Westerson, author of twelve Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mystery novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri also writes two paranormal series: “Booke of the Hidden,” and the “Enchanter Chronicles Trilogy,” the first of which is The Daemon Device. (Watch the

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native Jeri Westerson, author of twelve Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mystery novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri also writes two paranormal series: “Booke of the Hidden,” and the “Enchanter Chronicles Trilogy,” the first of which is The Daemon Device. (Watch the  And that, too, led to some research into what the interpretation of demons has been between the Judeo and Christian sides of scriptures. Jewish mysticism goes in some surprising directions. In Judaism, for instance, there is no Hell as Christians have defined it. No pitchfork Devil in charge of tormenting souls for all eternity. Instead, Jewish belief is that there cannot be eternal punishment for a finite life of sin. God just isn’t that vindictive. The writings talk of Gehenna—a place of waiting and working out one’s remorse for past sins (like purgatory)—and was the dwelling of the daemons. Its partner in another locale but Gehenna-adjacent is Sitra Achra, the place where all evil comes from.

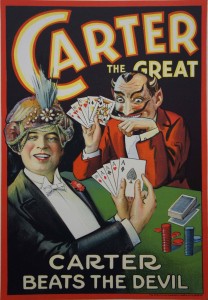

And that, too, led to some research into what the interpretation of demons has been between the Judeo and Christian sides of scriptures. Jewish mysticism goes in some surprising directions. In Judaism, for instance, there is no Hell as Christians have defined it. No pitchfork Devil in charge of tormenting souls for all eternity. Instead, Jewish belief is that there cannot be eternal punishment for a finite life of sin. God just isn’t that vindictive. The writings talk of Gehenna—a place of waiting and working out one’s remorse for past sins (like purgatory)—and was the dwelling of the daemons. Its partner in another locale but Gehenna-adjacent is Sitra Achra, the place where all evil comes from. Added to that, is the world of the nineteenth century magician. If you look at some of the posters from the era, there is plenty of use of demon imagery, where even the magician Carter “Beats the Devil.”

Added to that, is the world of the nineteenth century magician. If you look at some of the posters from the era, there is plenty of use of demon imagery, where even the magician Carter “Beats the Devil.” A big thanks to Jeri Westerson! She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Daemon Device to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson! She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Daemon Device to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes back Steve Bartholomew, who grew up in San Francisco but has lived other places such as Mexico City and New York. Now he holes up on the shores of a lake in northern California, away from crowds. He’s been writing since about age nine, published science fiction and some non-fiction, but now is mainly interested in history and historical fiction. He’s always loved history, but only began writing about it when introduced to a sidewheel steamship that sank in 1865, loaded with treasure. The more history Steve looks at, the more treasures he finds. To learn more about him and his books, visit his

Relevant History welcomes back Steve Bartholomew, who grew up in San Francisco but has lived other places such as Mexico City and New York. Now he holes up on the shores of a lake in northern California, away from crowds. He’s been writing since about age nine, published science fiction and some non-fiction, but now is mainly interested in history and historical fiction. He’s always loved history, but only began writing about it when introduced to a sidewheel steamship that sank in 1865, loaded with treasure. The more history Steve looks at, the more treasures he finds. To learn more about him and his books, visit his

A big thanks to Steve Bartholomew!

A big thanks to Steve Bartholomew! Relevant History welcomes back historical fiction author Janet Oakley, a history nerd and amateur gardener. Her fiction spans the mid-19th century to WW II with characters standing up for something in their own time and place. Her writing has been recognized with a 2013 Bellingham Mayor’s Arts Award, the Chanticleer Grand Prize for Tree Soldier, Goethe Grand Prize for The Jøssing Affair, 2018 Will Rogers Silver Medallion and 2018 WILLA Silver Awards for Mist-chi-mas: A Novel of Captivity. Timber Rose was a 2015 WILLA Award finalist. A UH Manoa grad, she has special memories of the 1877 Volcano House, often teaching there. To learn more about Janet and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes back historical fiction author Janet Oakley, a history nerd and amateur gardener. Her fiction spans the mid-19th century to WW II with characters standing up for something in their own time and place. Her writing has been recognized with a 2013 Bellingham Mayor’s Arts Award, the Chanticleer Grand Prize for Tree Soldier, Goethe Grand Prize for The Jøssing Affair, 2018 Will Rogers Silver Medallion and 2018 WILLA Silver Awards for Mist-chi-mas: A Novel of Captivity. Timber Rose was a 2015 WILLA Award finalist. A UH Manoa grad, she has special memories of the 1877 Volcano House, often teaching there. To learn more about Janet and her books, visit her  In 1823, Reverend William Ellis, an Englishman, made such a visit with American missionary, Asa Thurston. It was arduous journey of nearly twenty miles starting down by the ocean, crossing a lava desert and eventually arriving at the north end of Kilauea Crater. Ellis wrote, “We stopped and trembled.” He then went on to describe Kīlauea:

In 1823, Reverend William Ellis, an Englishman, made such a visit with American missionary, Asa Thurston. It was arduous journey of nearly twenty miles starting down by the ocean, crossing a lava desert and eventually arriving at the north end of Kilauea Crater. Ellis wrote, “We stopped and trembled.” He then went on to describe Kīlauea: In 1866, George W.C. Jones of Keauhou, Hawaii, who had made his fortune in pulu (a popular soft fiber from the hapu’u fern and used for upholstery stuffing), went in partnership with Charles and Jules Richardson to build a more substantial wood structure. Overlooking Kilauea Crater, the building had a pili thatch roof with four bedrooms, parlor, and dining room inside. Mark Twain came for a visit in 1866 and wrote about Volcano House in Roughing It:

In 1866, George W.C. Jones of Keauhou, Hawaii, who had made his fortune in pulu (a popular soft fiber from the hapu’u fern and used for upholstery stuffing), went in partnership with Charles and Jules Richardson to build a more substantial wood structure. Overlooking Kilauea Crater, the building had a pili thatch roof with four bedrooms, parlor, and dining room inside. Mark Twain came for a visit in 1866 and wrote about Volcano House in Roughing It: Over the decades, Volcano House changed owners several times. When the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company took over in in 1921, a new two-story wing was built, bringing the number of rooms to 115. Sadly, the 1877 structure was sawn apart and moved to a new location away from the cliff. There it served as quarters for the hotel employees and sometimes furniture storage. In 1940, it briefly functioned as an interim lobby and bar when the 1921 Volcano House burned down. It began to fall into disrepair after today’s present hotel was built.

Over the decades, Volcano House changed owners several times. When the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company took over in in 1921, a new two-story wing was built, bringing the number of rooms to 115. Sadly, the 1877 structure was sawn apart and moved to a new location away from the cliff. There it served as quarters for the hotel employees and sometimes furniture storage. In 1940, it briefly functioned as an interim lobby and bar when the 1921 Volcano House burned down. It began to fall into disrepair after today’s present hotel was built. A big thanks to Janet Oakley! She’ll give away one ebook copy of her cozy mystery, Volcano House, to one person who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Janet Oakley! She’ll give away one ebook copy of her cozy mystery, Volcano House, to one person who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes back Judith Starkston, author of the award-winning historical fantasy Priestess of Ishana and the Trojan War novel Hand of Fire. She has degrees in Classics from the University of California, Santa Cruz and Cornell. Priestess of Ishana combines history with magical elements found in Hittite rites, and in the series, Queen Puduhepa is renamed Tesha after the Hittite word for “dream.” (Read the post to find out why.) To learn more about Judith and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes back Judith Starkston, author of the award-winning historical fantasy Priestess of Ishana and the Trojan War novel Hand of Fire. She has degrees in Classics from the University of California, Santa Cruz and Cornell. Priestess of Ishana combines history with magical elements found in Hittite rites, and in the series, Queen Puduhepa is renamed Tesha after the Hittite word for “dream.” (Read the post to find out why.) To learn more about Judith and her books, visit her  Queen Puduhepa pressed her seal into the first extant peace treaty in history. The Treaty of Kadesh was between her kingdom of the Hittites (in what is now Turkey) and Rameses II, Pharaoh of Egypt, during the Late Bronze Age, in the thirteenth century BCE. In the twentieth century, her letters, treaties, religious codifications and judicial decrees came to light when archaeologists dug up the great cuneiform libraries of her capital, Hattusha.

Queen Puduhepa pressed her seal into the first extant peace treaty in history. The Treaty of Kadesh was between her kingdom of the Hittites (in what is now Turkey) and Rameses II, Pharaoh of Egypt, during the Late Bronze Age, in the thirteenth century BCE. In the twentieth century, her letters, treaties, religious codifications and judicial decrees came to light when archaeologists dug up the great cuneiform libraries of her capital, Hattusha. A big thanks to Judith Starkston! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Priestess of Ishana to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Judith Starkston! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Priestess of Ishana to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.