Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at Random Bits of Fascination—mainly about her fascination with Regency era history and its role in her fiction. Her newest novel, The Trouble to Check Her, was released March 2016. To learn more about her and her books, visit her group blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at Random Bits of Fascination—mainly about her fascination with Regency era history and its role in her fiction. Her newest novel, The Trouble to Check Her, was released March 2016. To learn more about her and her books, visit her group blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and Pinterest.

*****

A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope?

A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope?

The Hardwicke Act

Starting with the ‘why’: Marriage back at the start of the 1800s was pretty different than it is today. For many years marriage only required words of consent uttered by the parties involved (at least age fourteen for men and twelve for women) in front of two witnesses.

While that approach made things fairly simple, it proved a record-keeping nightmare as there was no real way to prove a marriage did or did not exist. To rectify this dilemma, the Hardwicke Act of 1753 stipulated:

* A couple needed a license or the reading of the banns to marry

* Parental consent if either was under the age of twenty one

* The ceremony must take place within a public chapel or church, by authorized clergy

* The marriage must be performed between eight a.m. and noon before witnesses

* The marriage had to be recorded in the marriage register with the signatures of both parties, the witnesses, and the minister.

Usually parental consent was the fly in the ointment, but sometimes, the reading of the banns might raise an objection. Perhaps one of the parties was promised to marry another, or worse, had already married another. Either could put a crimp on a young couple’s plans.

An obvious solution might be to go somewhere else to get married, like perhaps Scotland. Scottish law merely required two witnesses and a minimum age of sixteen for both parties. (Of course for now, we’ll ignore the fact that whether or not Scottish marriages were legally valid in England was a matter of some debate.)

Gretna Green was just nine miles from the last English staging post at Carlisle and just one mile over the border with Scotland. The town took advantage of the situation and made something of a business in quick marriages, not unlike Los Vegas today. Hence, it was known for elopements, and it became a favorite plot device.

The Trouble with Gretna Green

If it was so simple and convenient, why not go to Gretna Green to marry? Barring the fact that elopements were a good way to get ostracized from good society, there were practical considerations that made it unsuitable for many.

Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own.

Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own.

If one were moderately well off, they might purchase tickets on a public conveyance to go long distances. While better than walking, one could still only expect to travel five to seven miles per hour. Traveling twelve hours a day, with only moderate stops to change horses and deal with personal necessities, the trip would take about four days.

Four days packed in a carriage with as many other people as the proprietors could squeeze into the space and more sitting on top of the coach.

A lovely, romantic picture, yeah?

Luckily, Gretna Green was not the only option. Other locations were available to facilitate a clandestine marriage. Towns along the eastern borders of Scotland, like Lamberton, Paxton, Mordington, and Coldstream also catered to eloping couples. In some cases, the toll-keepers along the road provided the marriages at the tollhouses.

From the south, those willing to sail might go to Southampton, Hampshire and purchase passage to the Channel Islands. The Isle of Guernsey in particular provided another alternative for a quick marriage.

Far simpler and closer to home

A far less romantic but simpler, cheaper and closer to home alternative existed. All a couple really had to do was have their banns read for three consecutive weeks in a church, then have the ceremony performed.

In a large urban center, like London, parishes could be huge and the clergy hard-pressed to verify each couple’s age and residency. If a couple could manage to get to a large town, or better London itself, they could lose themselves in the crowd and get married the conventional way, and their families were unlikely to get word of it in time to prevent anything.

After such a wedding occurred, the only recourse an aggrieved parent had was to go to the church where the banns had been called and challenge that the banns had been mistaken or even fraudulent. The process was public, inconvenient and embarrassing and thus not very common.

Despite a Gretna Green (or other Scottish) elopement being a romantic idyll, marrying in a big city parish was by far the most likely way young people married against their parents’ wishes.

*****

A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

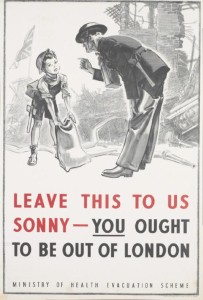

Planning for the event had begun in May 1938 as it became increasingly obvious the outbreak of hostilities was inevitable. Hansard, the official record of the proceedings in Parliament, reported work on the task in hand 2 February 1939. During a House of Commons debate on air raid precautions, in response to a question from the MP representing a Tyneside town, the Lord Privy Seal stated plans were then in preparation for evacuating Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gateshead schoolchildren.

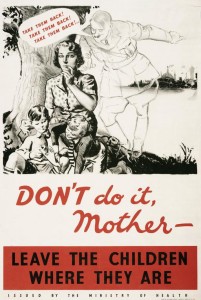

Planning for the event had begun in May 1938 as it became increasingly obvious the outbreak of hostilities was inevitable. Hansard, the official record of the proceedings in Parliament, reported work on the task in hand 2 February 1939. During a House of Commons debate on air raid precautions, in response to a question from the MP representing a Tyneside town, the Lord Privy Seal stated plans were then in preparation for evacuating Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gateshead schoolchildren. Many parents kept their children at home because they did not want to be separated from them. Another factor in their decision was the difficulty and expense of the travel needed for them to visit their evacuated children. Some evacuees were brought back when they fell ill or had accidents and older children who had contributed to the family income returned as they were still needed to do so.

Many parents kept their children at home because they did not want to be separated from them. Another factor in their decision was the difficulty and expense of the travel needed for them to visit their evacuated children. Some evacuees were brought back when they fell ill or had accidents and older children who had contributed to the family income returned as they were still needed to do so. A big thanks to Eric Reed. They’ll give away an ebook copy of The Guardian Stones to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Eric Reed. They’ll give away an ebook copy of The Guardian Stones to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes Barbara Schlichting, author of the “First Ladies” mystery series. Barbara has an undergraduate degree in elementary education and a master’s degree in special education. She studied at Bemidji State University and currently resides in Bemidji with her husband. Dolley Madison: The Blood Spangled Banner, a mystery that ties modern-day clues with historical features, follows a descendant of Dolley Madison who owns the First Lady White House Dollhouse Store in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Look for the release of Mary Lincoln: Words Can Kill in the fall of 2016. To learn more about Barbara and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Barbara Schlichting, author of the “First Ladies” mystery series. Barbara has an undergraduate degree in elementary education and a master’s degree in special education. She studied at Bemidji State University and currently resides in Bemidji with her husband. Dolley Madison: The Blood Spangled Banner, a mystery that ties modern-day clues with historical features, follows a descendant of Dolley Madison who owns the First Lady White House Dollhouse Store in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Look for the release of Mary Lincoln: Words Can Kill in the fall of 2016. To learn more about Barbara and her books, visit her  Dolley Madison was the most quintessential, bipartisan first lady to have ever lived in the White House. Her term began with Thomas Jefferson while her husband James Madison was secretary of state. She became Jefferson’s hostess for all state dinners and official functions since he was a widower. Jefferson called Dolley his first lady, which is how the title originated.

Dolley Madison was the most quintessential, bipartisan first lady to have ever lived in the White House. Her term began with Thomas Jefferson while her husband James Madison was secretary of state. She became Jefferson’s hostess for all state dinners and official functions since he was a widower. Jefferson called Dolley his first lady, which is how the title originated. A big thanks to Barbara Schlichting. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of Dolley Madison: The Blood Spangled Banner to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Barbara Schlichting. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of Dolley Madison: The Blood Spangled Banner to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only. Relevant History welcomes back Judy Alter, a native of Chicago who lives in Texas but never lost her love for the Windy City and its lake. She is the author of over seventy books, fiction and nonfiction, adult and young-adult, including fictional biographies Libbie (Elizabeth Bacon Custer); Jessie (Jessie Benton Frémont); Cherokee Rose (Lucille Mulhall, first rodeo girl roper); and Sundance, Butch and Me (Etta Place). Today she writes contemporary cozy mysteries. She is the single parent of four children and the grandmother of seven. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes back Judy Alter, a native of Chicago who lives in Texas but never lost her love for the Windy City and its lake. She is the author of over seventy books, fiction and nonfiction, adult and young-adult, including fictional biographies Libbie (Elizabeth Bacon Custer); Jessie (Jessie Benton Frémont); Cherokee Rose (Lucille Mulhall, first rodeo girl roper); and Sundance, Butch and Me (Etta Place). Today she writes contemporary cozy mysteries. She is the single parent of four children and the grandmother of seven. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  What does it have to do with the story of Cissy and Potter Palmer in my book The Gilded Cage? It is woven into the novel partly as the historical background and partly because it shows the difference in their reactions. Palmer condemned the protestors and claimed they should have stayed home. Cissy believed in taking philanthropy to those who need it. In the novel she bundles food and blankets to take to the families of the arrested men. Police, she told her son, would take care of their own—the families of those officers who died.

What does it have to do with the story of Cissy and Potter Palmer in my book The Gilded Cage? It is woven into the novel partly as the historical background and partly because it shows the difference in their reactions. Palmer condemned the protestors and claimed they should have stayed home. Cissy believed in taking philanthropy to those who need it. In the novel she bundles food and blankets to take to the families of the arrested men. Police, she told her son, would take care of their own—the families of those officers who died. A big thanks to Judy Alter. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The Gilded Cage to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Judy Alter. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The Gilded Cage to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only. Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at

Relevant History welcomes Regency romance author Maria Grace, who has her PhD in Educational Psychology and is a sixteen-year veteran of the university classroom, where she taught courses in human growth and development, learning, test development and counseling. None of which have anything to do with her undergraduate studies in economics/sociology/managerial studies/behavior sciences. She blogs at  A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope?

A couple eloping to Grenta Green is a fairly common plot device for romances set in the early 1800s. But why was it done (other than because it sounds really romantic), and what cheaper, easier alternatives were at hand for a couple inclined to elope? Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own.

Gretna Green is three hundred twenty miles from London, the largest British population center of the early 1800s. My local highways boast an 80 or 85 mile-per-hour speed limit, so I can travel that distance in half a day, no bother. In the early 1800s those speeds were unheard of. Most people walked. Everywhere. Only the very wealthy had horses and carriages of their own. A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Maria Grace. She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Trouble to Check Her to two people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Relevant History welcomes P.A. De Voe, an anthropologist, Asian specialist, and incorrigible magpie for collecting seemingly irrelevant information. Her first published mystery, A Tangled Yarn, is a contemporary cozy. In her current writing, however, she has jumped back in time and place, immersing her stories in the Ming Dynasty. She’s published several historical short stories, From Judge Lu’s Ming Dynasty Case Files, in anthologies and online. Her newly published adventure/mystery YA trilogy (Hidden, Warned, and Trapped) takes place in 1380 A.D. China. To learn more about P.A. De Voe and her books and to get a free short story, visit her

Relevant History welcomes P.A. De Voe, an anthropologist, Asian specialist, and incorrigible magpie for collecting seemingly irrelevant information. Her first published mystery, A Tangled Yarn, is a contemporary cozy. In her current writing, however, she has jumped back in time and place, immersing her stories in the Ming Dynasty. She’s published several historical short stories, From Judge Lu’s Ming Dynasty Case Files, in anthologies and online. Her newly published adventure/mystery YA trilogy (Hidden, Warned, and Trapped) takes place in 1380 A.D. China. To learn more about P.A. De Voe and her books and to get a free short story, visit her  A big thanks to P.A. DeVoe. She will give away a paperback copy of Hidden to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to P.A. DeVoe. She will give away a paperback copy of Hidden to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.