Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog. The week of 1–7 July 2011, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom Giveaway Hop,” accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one with a Revolutionary War theme. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

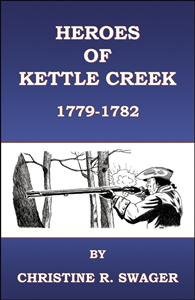

Relevant History welcomes YA author Christine Swager. She started writing about the Revolutionary War in the South when her graduate students at the University of South Carolina (in-service teachers) complained that there was little literature for students which would help them understand what it was like to live and fight in that war. Chris writes for teachers and young adults and, as a storyteller, is unapologetically partial to Patriot militia. She had lectured in Illinois and Michigan as well as venues in the South and is the recipient of the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution award for Youth Education Lifetime Achievement. For more information, check her Facebook page.

Relevant History welcomes YA author Christine Swager. She started writing about the Revolutionary War in the South when her graduate students at the University of South Carolina (in-service teachers) complained that there was little literature for students which would help them understand what it was like to live and fight in that war. Chris writes for teachers and young adults and, as a storyteller, is unapologetically partial to Patriot militia. She had lectured in Illinois and Michigan as well as venues in the South and is the recipient of the Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution award for Youth Education Lifetime Achievement. For more information, check her Facebook page.

*****

The British did not find the South Carolina summer of 1780 very comfortable. Charleston had fallen to the British in May, and British posts had been established throughout the state for billeting British troops (mostly Provincials), and recruiting Loyalist or Tory militia. On the surface, it appeared that South Carolina was effectively occupied. The Patriot militia would change that. Although there was militia in the field throughout the state, this account concerns the activities in the northwest corner of South Carolina, in the vicinity of present day Spartanburg.

In July, Colonel Charles McDowell of North Carolina called militia from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia to muster at a camp at Earle’s Ford on the Pacolet River. Among the militia who responded were Col. Isaac Shelby of Washington District of Western North Carolina (now East Tennessee), with 200 men of Overmountain militia, and Col. Elijah Clarke with his Wilkes County militia from Georgia. These men had a long history of fighting Indians, and Clarke’s men had been fighting the British since the occupation of Georgia in 1778.

The British had recently been pushed out of Gowen’s Old Fort and Fort Prince in the area, leaving only one fortification for their protection, Fort Anderson, also known as Fort Thicketty. Shelby and Clarke moved against Fort Thicketty, and the fort’s commander surrendered without firing a shot on 30 July. The Patriot militia captured 200 weapons, powder, shot and supplies.

Moving south toward the British outpost of Ninety-Six, Clarke was attacked by Provincials commanded by Capt. James Dunlap, who had been recently thwarted in an attempt to ambush part of the Spartan Regiment at Cedar Springs. Shelby, who had been camped nearby, joined the battle, which raged from close to Cedar Springs through Wofford’s Ironworks and across Lawson’s Fork.

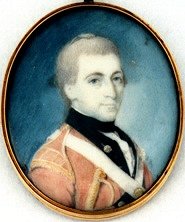

At first Dunlap was forced to retreat but was met by his commander, Major Patrick Ferguson, who renewed the attack. In the fighting Clarke suffered sabre wounds to the head and neck and was briefly held prisoner. Shaking off his captors, he returned to the fight. When the Patriots gained the high ground by the Pacolet River, Ferguson saw the futility of an attack and retreated. The encounter had cost the British dearly. This was the first time that Ferguson had met and been thwarted by Clarke and Shelby, and it would not be the last time.

At first Dunlap was forced to retreat but was met by his commander, Major Patrick Ferguson, who renewed the attack. In the fighting Clarke suffered sabre wounds to the head and neck and was briefly held prisoner. Shaking off his captors, he returned to the fight. When the Patriots gained the high ground by the Pacolet River, Ferguson saw the futility of an attack and retreated. The encounter had cost the British dearly. This was the first time that Ferguson had met and been thwarted by Clarke and Shelby, and it would not be the last time.

With Shelby’s militia nearing the completion of their enlistment and wanting to strike one more blow, the opportunity came when McDowell learned of a Loyalist militia encampment at Musgrove’s Mill on the Enoree River. The British had suffered several wounded in the previous engagements, and they were being housed at Musgrove’s Mill. Shelby and Clarke prepared to move south and attack. They were joined by Colonel James Williams of the Little River militia. Williams had been in camp with Thomas Sumter, but that militia was focused on the Camden area and the British troops posted there. Williams and the men who accompanied him to McDowell’s camp (Thomas Young, Christopher Brandon, Andrew Barry), were men whose homes and families were threatened by the British posted at Ninety-Six.

The combined militia rode through the night on paths to avoid Major Ferguson’s camp, located a few miles to the east. They intended a surprise attack at daybreak. However, they were discovered as they approached the Enoree River, so the element of surprise was lost. Further, they learned that a large group of Provincials, moving to join Ferguson, had arrived in camp the night before. Now, knowing that they were outnumbered by superior numbers and troops which were professionally trained and experienced, the decision was made to fight as the horses were too exhausted from the August heat to effect a retreat.

They hastily threw up some logs to form breastworks on a wooded ridge across the river from the British encampment and lured the British into attacking. In the exchange of fire during the brief battle, almost all of the British Provincial officers and the Tory militia officers were wounded or killed. The Tory militia fled the field with the British close behind. They rushed through their camp and down the road towards their post at Ninety-Six with the Patriots in pursuit.

Clarke, Shelby and Williams were determined to follow them to Ninety-Six and attack. However, a courier arrived with news of the British victory at Camden. Now, with no Continental Army in the area, the British would be free to concentrate their campaign against the Spartanburg area. McDowell advised this militia to retreat before they were cut off from their homes. However, before they departed, these three militia colonels—Clarke of Georgia, Shelby of North Carolina, and Williams of South Carolina—determined that the way to deal with Ferguson’s campaign in the area was to mass the militia. They would not let Ferguson engage one group at a time, but would keep in touch and if one were threatened, they would all respond.

Shortly after the Patriots moved north, Major Patrick Ferguson arrived. Learning of the catastrophe, (63 dead, 90 wounded and 70 captured by the Patriots), Ferguson rode to overtake the Patriots and recover his prisoners. However, after a few miles, Ferguson saw there was no possibility of overtaking his enemy so he returned to take charge of the field. For the second time, Major Patrick Ferguson had been bested by Clarke and Shelby.

The last of September, Elijah Clarke was moving north out of Georgia across the mountains to join Isaac Shelby. Major Ferguson moved west to intercept Clarke but failed. Ferguson issued Shelby an ultimatum. Shelby was to lay down his arms and swear allegiance to King George, or Ferguson would hang Shelby and his men and lay waste their settlements with fire and sword.

The last of September, Elijah Clarke was moving north out of Georgia across the mountains to join Isaac Shelby. Major Ferguson moved west to intercept Clarke but failed. Ferguson issued Shelby an ultimatum. Shelby was to lay down his arms and swear allegiance to King George, or Ferguson would hang Shelby and his men and lay waste their settlements with fire and sword.

Shelby, true to the strategy agreed upon at Musgrove’s Mill, called out the militia. The massed militia surrounded Ferguson on King’s Mountain, killing Ferguson and destroying his entire force. The militia success at King’s Mountain was what British General Clinton would refer to as “the first in a series of unfortunate events.”

*****

A big thanks to Chris Swager. She’ll give away a print copy of her YA book Heroes of Kettle Creek to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment by Monday 4 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of the winner on my blog the week of 11 July. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Chris Swager. She’ll give away a print copy of her YA book Heroes of Kettle Creek to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment by Monday 4 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of the winner on my blog the week of 11 July. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.