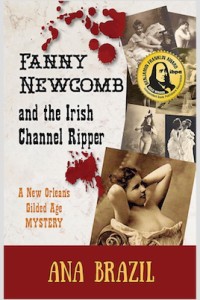

Relevant History welcomes Ana Brazil, author of the historical mystery Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper (Sand Hill Review Press) and winner of the Independent Book Publishers Association 2018 Gold Medal for Historical Fiction. Ana explored the historic houses of Virginia as a teenager, earned her Master’s degree in American history from Florida State University, and traveled her way through Mississippi as an architectural historian. She also spent one very long, very hot summer in New Orleans researching content for her Master’s thesis. Ana, her husband, and her dog Traveller live in the beautiful Oakland foothills. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes Ana Brazil, author of the historical mystery Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper (Sand Hill Review Press) and winner of the Independent Book Publishers Association 2018 Gold Medal for Historical Fiction. Ana explored the historic houses of Virginia as a teenager, earned her Master’s degree in American history from Florida State University, and traveled her way through Mississippi as an architectural historian. She also spent one very long, very hot summer in New Orleans researching content for her Master’s thesis. Ana, her husband, and her dog Traveller live in the beautiful Oakland foothills. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, and Pinterest.

*****

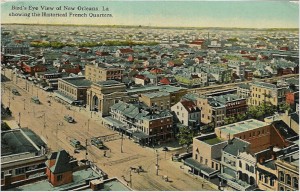

I’ve always been attracted to cities. Not humongous, out-of-control, no-place-to-walk-or-breathe-in cities, but gentler, gracious, and smile-when-you-meet-new-people cities. Southern cities like Tallahassee, Vicksburg, and New Orleans.

When I wrote my debut historical mystery Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, I worked hard to make sure that I presented the historical environment of 1889 New Orleans correctly. I walked around the Irish Channel neighborhood, photographed all kinds of buildings, toured St. Alphonsus and St. Mary Catholic Churches, and, of course, shopped as much as possible in the boutiques of historic Magazine Street!

When I wrote my debut historical mystery Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper, I worked hard to make sure that I presented the historical environment of 1889 New Orleans correctly. I walked around the Irish Channel neighborhood, photographed all kinds of buildings, toured St. Alphonsus and St. Mary Catholic Churches, and, of course, shopped as much as possible in the boutiques of historic Magazine Street!

I wanted to make sure that I described the buildings, banquettes, electric streetlights (yes, they existed), and streets traveled by the mule-driven streetcars as accurately as possible.

I also dug into the newspapers, city directories, and city “booster” materials from the period. And as a final way to understand the physical environment of 1889 New Orleans—to make sure that I didn’t locate a house of prostitution where a church existed, or sink Charity Hospital into a drainage canal—I explored the city through the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps (aka “Sanborn maps”).

What are Sanborn maps?

I’m so glad that you asked! From 1866 to the mid-1960’s, the Sanborn Map Publishing Company of New York City created complex footprint maps of approximately 13,000 American cities. Fire insurance companies used these maps to estimate the fire risks for individual buildings and decide how much to charge the building owners for fire insurance.

I’m so glad that you asked! From 1866 to the mid-1960’s, the Sanborn Map Publishing Company of New York City created complex footprint maps of approximately 13,000 American cities. Fire insurance companies used these maps to estimate the fire risks for individual buildings and decide how much to charge the building owners for fire insurance.

I was introduced to Sanborn maps when I worked as an architectural historian for the Mississippi Department of Archives. My job was to evaluate and nominate historic buildings and places for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. The Sanborn maps were vitally helpful.

Although Sanborn maps are a treasure trove for architectural historians, historians, and historical novelists, that’s not where their value ends. If you’re an archaeologist, genealogist, realtor, public works employee, or geographer, you can use these maps to unlock the secrets of your city, neighborhood, block, or building.

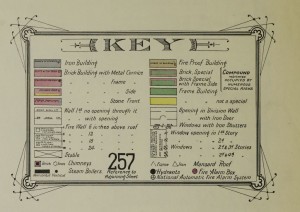

All you need is a key

Every group of city maps had a “key” similar to the one in this image. Once you understood the key, you could understand everything about the buildings on the map.

Every group of city maps had a “key” similar to the one in this image. Once you understood the key, you could understand everything about the buildings on the map.

.

.

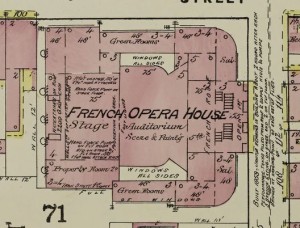

As this example of New Orleans’ French Opera House shows, the maps displayed the footprints of building (to scale), building materials used (red=brick, yellow=frame, blue=stone), existing firewall information, locations of available water reservoirs, other buildings in the area, and whether the building had a watchman. Just to name a few of the map attributes.

As this example of New Orleans’ French Opera House shows, the maps displayed the footprints of building (to scale), building materials used (red=brick, yellow=frame, blue=stone), existing firewall information, locations of available water reservoirs, other buildings in the area, and whether the building had a watchman. Just to name a few of the map attributes.

This information—about how people lived, worked, and entertained themselves—cannot be found anywhere else! And these are the types of details that I love to use when creating my historical fiction.

When I began writing Fanny Newcomb and the French Quarter Laudanum Lover—the (in-progress) second book in my Fanny Newcomb trilogy—I wanted to understand more about New Orleans’ historic French Quarter. Specifically, I wanted to know where the Italian restaurants, drug stores, tobacco manufacturers, and “female boarding” houses (an oft-used Sanborn map euphemism for houses of prostitution) were located in the late 1880’s.

This image displays what I call the “big view,” which shows some of areas that were surveyed by the Sanborn Company. The “42” in pink refers to Page 42 of the book and is the location of part of the French Quarter from Jackson Square and St. Louis Cathedral to Canal Street.

This image displays what I call the “big view,” which shows some of areas that were surveyed by the Sanborn Company. The “42” in pink refers to Page 42 of the book and is the location of part of the French Quarter from Jackson Square and St. Louis Cathedral to Canal Street.

.

.

Here is a close-up image of part of Page 42 showing Jackson Square on the bottom center and St. Louis Cathedral above it. Most of the buildings and green spaces shown in this map still exist, although their uses have changed. But look at some of these 19th century uses!

Here is a close-up image of part of Page 42 showing Jackson Square on the bottom center and St. Louis Cathedral above it. Most of the buildings and green spaces shown in this map still exist, although their uses have changed. But look at some of these 19th century uses!

Cooper shop

Carpenter

Snuff and fine cut tobacco factory

State arsenal

Gun & locksmith

Paints & oils

All of these building uses contribute to the flavor of New Orleans 1889. It would have been impossible to understand “the business of Jackson Square” without a Sanborn map.

Although I did find a tobacco manufacturer in this area, there were no Italian restaurants or drug stores. And—mostly likely because of the Cathedral, Courts, and Police Station in the vicinity—there were no female boarding houses in this area of the French Quarter. Although there were many, many female boarding houses just blocks away from Jackson Square.

I hope this short tour through late 19th century New Orleans illuminates the importance of historic Sanborn maps, how fun they are to look at, and how much they can tell you about your chosen locale! To make your foray into Sanborn maps as easy as possible, the Library of Congress—owner of the largest collection of Sanborn maps—has made their maps available online. In addition, many university libraries throughout the United States own sets of Sanborn maps (bound in books which can weigh up to 30 pounds!) and—once you put on a pair of white gloves—you can research directly in those books.

One more bit of good news: in the late 18th century, insurance companies began mapping the buildings of London, and other countries also have their share of “Sanborn-equivalent” city maps. But since Gilded Age New Orleans is my city, I’ll have to let another Relevant History blogger share the secrets of other city maps with you.

Note: All Sanborn map screenshots in this post are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

*****

A big thanks to Ana Brazil! She’ll give away a 13 oz. can of New Orleans’ Cafe du Monde’s French Roast Coffee and a Kindle ebook copy of Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Ana Brazil! She’ll give away a 13 oz. can of New Orleans’ Cafe du Monde’s French Roast Coffee and a Kindle ebook copy of Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

.

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.