Have you been watching the excellent adaptation of Diana Gabaldon’s historical novel, Outlander, on the Starz channel? I have, and I also belong to an Outlander Facebook discussion group. Since my first book was published, readers have told me that my series appeals to fans of Gabaldon’s books because of certain settings and themes. Redcoats, war, 18th century, amoral characters, civilians in peril—hey, what’s not to like? So many interesting issues and points have emerged from the Outlander episodes that I’ve decided to explore some of them here on my blog.

*****

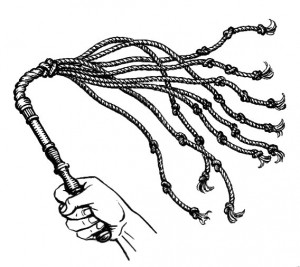

Early in season one of Outlander, viewers were shown the scarred back of character Jamie Fraser—the result of his being flogged with a cat-o’-nine-tails by a wacko, sadistic British officer. From all the research I’ve done into the American Revolution, I knew about the cat and the kind of damage it could do. Flogging permanently disfigured a person’s back. The makeup job done to actor Sam Heughan’s back to represent the scarring looked like what I expected, accurately depicting the traumatic damage.

Early in season one of Outlander, viewers were shown the scarred back of character Jamie Fraser—the result of his being flogged with a cat-o’-nine-tails by a wacko, sadistic British officer. From all the research I’ve done into the American Revolution, I knew about the cat and the kind of damage it could do. Flogging permanently disfigured a person’s back. The makeup job done to actor Sam Heughan’s back to represent the scarring looked like what I expected, accurately depicting the traumatic damage.

But outrage, disbelief, and horror exploded in comments from members of the discussion group. Most had no idea that flogging with a cat could produce such trauma. Even after a flashback of the gruesome event was shown in episode six, the outrage, disbelief, and horror persisted. I wondered why there was such a disconnect about flogging.

Many people of my generation and earlier were spanked or “switched” if they were naughty children. That level of corporal punishment is mild compared to flogging, but if it’s a viewer’s only point of reference, the flogging in Outlander comes as a huge, horrific surprise. Also, in first-world countries, corporal punishment of children and criminals has been downplayed for several generations in favor of other forms of punishment.

Plus, in the last century, especially the first seven decades of the 20th century, I think that Hollywood’s depiction of “good guys” played a crucial role in the development of these mistaken beliefs about flogging. These Hollywood heroes had stiff upper lips when it came to pain and could unrealistically “take a lickin’ and keep on tickin’.” For all their trouble, villains seldom got more than a grunt out of these superhuman hero characters. The following two examples show you what I mean.

Errol Flynn portrayed many swashbuckling heroes on the Silver Screen. Here he is in the movie “Against All Flags.” His character, a Navy officer, is receiving twenty lashes on deck while the crew watches. It’s a ruse that his superiors concocted to convince everyone that he’s in disgrace so his reputation will precede him, and he can credibly infiltrate the villains’ operations. Aside from being a bit sweaty and emitting an occasional grunt of annoyance, Flynn’s character takes those twenty lashes in stride. He then moves on to getting dressed, hunting down the bad guys with sprightly energy, and (because he’s Errol Flynn) seducing a defiant and lovely woman. In reality, twenty lashes was a rather light sentence that might be delivered for minor crimes; often soldiers and sailors received at least fifty lashes. But those twenty would have torn the skin on a man’s back repeatedly. He’d have bled through his shirt, assuming he could have tolerated the pain of fabric rubbing his injured back. For several days afterward, he’d have been far too stiff and sore to gallivant around and seduce women, and he’d have carried scars from the flogging for the rest of his life.

Errol Flynn portrayed many swashbuckling heroes on the Silver Screen. Here he is in the movie “Against All Flags.” His character, a Navy officer, is receiving twenty lashes on deck while the crew watches. It’s a ruse that his superiors concocted to convince everyone that he’s in disgrace so his reputation will precede him, and he can credibly infiltrate the villains’ operations. Aside from being a bit sweaty and emitting an occasional grunt of annoyance, Flynn’s character takes those twenty lashes in stride. He then moves on to getting dressed, hunting down the bad guys with sprightly energy, and (because he’s Errol Flynn) seducing a defiant and lovely woman. In reality, twenty lashes was a rather light sentence that might be delivered for minor crimes; often soldiers and sailors received at least fifty lashes. But those twenty would have torn the skin on a man’s back repeatedly. He’d have bled through his shirt, assuming he could have tolerated the pain of fabric rubbing his injured back. For several days afterward, he’d have been far too stiff and sore to gallivant around and seduce women, and he’d have carried scars from the flogging for the rest of his life.

Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock are considered icons and hero figures almost five decades after the debut of classic Star Trek on primetime TV. This image, which provides excellent fodder for those who write slash fanfic, shows Kirk and Spock in a jail cell right after futuristic Nazis have flogged them in the episode “Patterns of Force.” To break the lock on their jail cell, Spock stands on Kirk’s freshly-flogged back so he can reach a light bulb and activate a laser-producing gizmo in his wrist. All Kirk does is grunt a little and kvetch about how the Nazis did a thorough job on his back. The two then escape the cell, beat up some Nazis who try to restrain them, and steal their uniforms. In reality, the “thorough job” any Nazi (c’mon, a Nazi, folks) would have done on Kirk and Spock would have resulted in shredded skin on their backs and incapacitation for both men.

Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock are considered icons and hero figures almost five decades after the debut of classic Star Trek on primetime TV. This image, which provides excellent fodder for those who write slash fanfic, shows Kirk and Spock in a jail cell right after futuristic Nazis have flogged them in the episode “Patterns of Force.” To break the lock on their jail cell, Spock stands on Kirk’s freshly-flogged back so he can reach a light bulb and activate a laser-producing gizmo in his wrist. All Kirk does is grunt a little and kvetch about how the Nazis did a thorough job on his back. The two then escape the cell, beat up some Nazis who try to restrain them, and steal their uniforms. In reality, the “thorough job” any Nazi (c’mon, a Nazi, folks) would have done on Kirk and Spock would have resulted in shredded skin on their backs and incapacitation for both men.

Flogging with a cat-o’-nine-tails was a common, flexible punishment for 18th-century soldiers and sailors convicted of a wide range of infractions. The experience that men received from flogging varied, as the whip could also be made of leather, and the knots could contain sharp objects like metal spikes to inflict an additional level of damage.

Flogging with a cat-o’-nine-tails was a common, flexible punishment for 18th-century soldiers and sailors convicted of a wide range of infractions. The experience that men received from flogging varied, as the whip could also be made of leather, and the knots could contain sharp objects like metal spikes to inflict an additional level of damage.

Trained soldiers and sailors were a valuable military investment in the 18th-century, thus the desired outcome of flogging wasn’t usually the recipient’s death. That meant that often the flogging was delivered by a boy who didn’t have the upper body strength of a man. (Here’s an update/correction on that statement.) Floggings were usually made public. The recipient’s company mates were required to turn out and watch him be flogged. The experience bonded all of them in a grisly way. After a flogging, the man was far less likely to screw up again because his mates were keeping him in line—and keeping themselves in line. I show this briefly in chapter thirty-five of my book Camp Follower: A Mystery of the American Revolution.

One more point about flogging. While it was considered punishment, the flogging that Jamie Fraser received in Outlander also demonstrated the psychological effectiveness of torture—and I don’t just mean torture of Jamie. We’re used to thinking of most forms of torture as a way to get someone to divulge information, right? But torture is actually not too effective at that. Studies have shown that when people are tortured, they say anything to make the agony stop. Most of the time, the information they spill is useless.

So if the torture wasn’t just for Jamie (who actually withstood it and didn’t give the loco villain what he wanted), who was it for? It was for the townsfolk who were witnessing the flogging. If you watch the episode, notice their reactions. The villain turned the flogging into a weapon of terror and made it public to keep the civilians in line. And he delivered the flogging himself to give it a personal touch.

Flogging, corporal punishment in the #18thCentury, and #Outlander http://bit.ly/1rV2zSR #history #AmRev

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

How do you think my protagonists Sophie Barton and Michael Stoddard would respond if they were suddenly transported from the American Revolution to 21st-century Miami? Check out my tongue-in-cheek response in this fun interview of me on Raquel Reyes’s Miami blog.

How do you think my protagonists Sophie Barton and Michael Stoddard would respond if they were suddenly transported from the American Revolution to 21st-century Miami? Check out my tongue-in-cheek response in this fun interview of me on Raquel Reyes’s Miami blog.