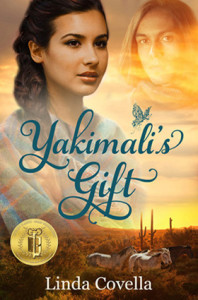

Relevant History welcomes award-winning children’s author Linda Covella, whose varied work background and education has led her down many paths. But one thing she never strayed from is her love of writing. In writing for kids and teens, she hopes to bring to them the feelings books gave her when she was a child: the worlds they opened, the things they taught, the feelings they expressed. Linda has been a member of the Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) since 2002. She lives in Santa Cruz, CA with her husband, Charlie, and dog, Ginger. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Pinterest, and Google+.

Relevant History welcomes award-winning children’s author Linda Covella, whose varied work background and education has led her down many paths. But one thing she never strayed from is her love of writing. In writing for kids and teens, she hopes to bring to them the feelings books gave her when she was a child: the worlds they opened, the things they taught, the feelings they expressed. Linda has been a member of the Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) since 2002. She lives in Santa Cruz, CA with her husband, Charlie, and dog, Ginger. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Pinterest, and Google+.

*****

Issues at the forefront of the news today—immigration and race, religion, and the treatment of women—were also important factors that, in 1775, helped shape the future of California and even the United States. Here I discuss these issues in the context of a colonization expedition in 1775–1776 from Mexico to California led by Juan Bautista de Anza, which is the setting for my novel Yakimali’s Gift.

Race relations

In 18th-century Mexico, New Spain, there were distinct classes depending on a person’s heritage. Those with “pure” Spanish blood enjoyed many societal privileges. Otherwise, people were labeled mestizo (Spanish and Indian), mulatto (Spanish and African), coyote (mestizo and Indian), or castizo (Spanish and mestizo).

Over two hundred years later, race and immigration are still issues that divide us here in the United States, as well as other countries. The Anza expedition brought some of the first Spanish and Mexican colonists to California. When I learned of this expedition, I was surprised that, especially since I lived in California, we were only taught about the settlers from the Eastern United States. I believe if we learn more about how and why people come to this country, we’ll better understand and accept the cultures and diversity that make the United States so special.

The Spanish mission to convert the Indians

Today, many people find it difficult to accept different religious beliefs; this was also the case in 1775 New Spain. On the expedition, Pima and Yuma Indians traded produce and chickens with Anza and the colonists for tobacco and beads. The Spaniards, shocked by the Indians’ scant clothing, were intent on dressing them in a “more civilized” manner, as well as converting them to Christianity. The Pimas had their own religious beliefs and gods. They honored Elder Brother and Earth Doctor. They didn’t believe in an afterlife of heaven or hell, reward or punishment. Instead, their souls went to Morning Base where they celebrated with dancing and feasting.

Before 1775, many Pimas were coerced or forced to live at the Spanish missions. And in 1751, they revolted, claiming brutality and land theft. Peace was eventually negotiated. Spanish colonization efforts were suspended.

In 1767, Franciscan priests replaced the Jesuits in New Spain, and the Franciscans continued the Spanish undertaking to convert the Indians. As the missions rose in California, conflicts between the Indians and Spaniards continued. And today, Native Americans still struggle to have their voices heard and conflicts resolved throughout the United States.

Women and children on the expedition

Over half of the colonists on de Anza’s expedition in 1775 were women and children. Most of my sources are from the male perspective, but I wanted to know more about the women and children. Who were they? Why did they choose to go on this arduous journey? What were they leaving behind, and what did they hope for their future? This is what inspired me to write Yakimali’s Gift from the perspective of fifteen-year-old Fernanda.

Over half of the colonists on de Anza’s expedition in 1775 were women and children. Most of my sources are from the male perspective, but I wanted to know more about the women and children. Who were they? Why did they choose to go on this arduous journey? What were they leaving behind, and what did they hope for their future? This is what inspired me to write Yakimali’s Gift from the perspective of fifteen-year-old Fernanda.

The diaries of Anza and Father Pedro Font, one of three Franciscan priests on the expedition, give just cursory mention of the women’s experience, and almost nothing about the children. For instance, Anza briefly writes about the death of a woman during childbirth on the first night of the journey, 24 October 1775, without even mentioning her name (which was Manuela Feliz), and then goes on to talk about the weather:

At three o’clock in the morning, it not having been possible by means of the medicines which had been applied in the previous hours, to remove the afterbirth from our mother, other various troubles befell her. As a result she was taken with paroxysms of death, and after the sacraments of penance and extreme unction had been administered to her, with the aid of the fathers who accompany us she rendered up her spirit at a quarter to four. At seven o’clock today it began to rain, and continued until half past ten…

One character in my novel, Maria Feliciana Arballo, was a real-life woman who went on the journey. At that time in Mexico, women of all classes were expected to be modest, unassertive, and devoted to God and home. Women could choose their husbands; however, they needed parental consent if they were under the age of twenty-five.

Because of the strict class structure, mixed marriages were frowned upon. It’s believed that Feliciana came from “pure” Spanish ancestry, and her parents disapproved of her marriage to José Gutierrez, a mestizo. Possibly to escape the prejudicial Mexican society, Feliciana and José decided to join the expedition. However, José died before the journey began. Still, Feliciana, with her two young daughters, chose to go on the journey.

Besides her two daughters from her first marriage, Feliciana had seven more children with her second husband, Juan Lopez. Many of her descendants became important figures in California history, including one daughter who was granted more than 8,000 acres in what is now Santa Rosa in northern California. Her husband had died, and she was one of only a few unmarried women to receive such a grant.

Benicia, the California capital in 1853-1854, was named after Feliciana’s granddaughter. One grandson, Andrés Pico, was the Commander-in-Chief of the Mexican military during the Mexican-American War, and his brother, Pío Pico, was the last Mexican governor of California before it became part of the United States in 1850.

Feliciana’s great-grandson, Romualdo Pacheco, became the State of California’s first and only Hispanic governor in 1875. He promoted the establishment of the University of California.

A story of hope

In the end, for me, Yakimali’s Gift is a story of hope. Hope that, like Fernanda, we have the determination and passion to live the lives we truly desire among the people we love. Hope that we value all people’s contributions regardless of gender or race. And hope that we appreciate the richness of our country’s diversity.

*****

A big thanks to Linda Covella. She’ll give away ebook copies of Yakimali’s Gift to three people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Linda Covella. She’ll give away ebook copies of Yakimali’s Gift to three people who contribute comments on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.