Relevant History welcomes back Catherine Curzon, a royal historian and author of Life in the Georgian Court, Kings of Georgian Britain, and Queens of Georgian Britain. Her work has been featured online by “BBC History Magazine” and in publications including Explore History, All About History, History of Royals, and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has spoken at venues including the Royal Pavilion, Lichfield Guildhall, the National Maritime Museum, and Dr Johnson’s House. Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film. Her novels include The Crown Spire, The Star of Versailles, and The Mistress of Blackstairs. She lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Pinterest, and Instagram.

Relevant History welcomes back Catherine Curzon, a royal historian and author of Life in the Georgian Court, Kings of Georgian Britain, and Queens of Georgian Britain. Her work has been featured online by “BBC History Magazine” and in publications including Explore History, All About History, History of Royals, and Jane Austen’s Regency World. She has spoken at venues including the Royal Pavilion, Lichfield Guildhall, the National Maritime Museum, and Dr Johnson’s House. Catherine holds a Master’s degree in Film. Her novels include The Crown Spire, The Star of Versailles, and The Mistress of Blackstairs. She lives in Yorkshire atop a ludicrously steep hill. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Pinterest, and Instagram.

*****

The reign of George I seemed to be beset by challenges and opposition, with domestic and political thorns never far from his side. In Parliament he looked increasingly to the likes of Sir Robert Walpole for guidance whilst in public, he tried and failed to cultivate the image of a social sort of sovereign. Yet no matter what he did, trouble was always following George I.

And nothing was more troublesome than the South Sea Bubble.

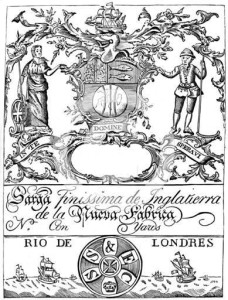

The South Sea Bubble has become legendary, synonymous with ruin and bankruptcy, with big business running rampantly out of control. It starts with a name, and not a very memorable name. The company behind all the trouble was officially known as The Governor and Company of the Merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of fishing. Created in 1711, the organisation became better known as the South Sea Company, a far more manageable moniker!

The South Sea Bubble has become legendary, synonymous with ruin and bankruptcy, with big business running rampantly out of control. It starts with a name, and not a very memorable name. The company behind all the trouble was officially known as The Governor and Company of the Merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of fishing. Created in 1711, the organisation became better known as the South Sea Company, a far more manageable moniker!

The gamble

The company took a gamble and based much of its business model reliant on monopolising South American trade. The company assumed that once the War of Spanish Succession ended they would be free to commence trading, and stocks sold well. The company’s reputation was helped when king himself became its governor in 1718!

In 1719, the company offered to buy up the national debt of Great Britain, ploughing millions into the national war chest. George listened to the canny lobbying of his mistress, Melusine von der Schulenberg, and though he wholeheartedly supported the scheme, Walpole had strong reservations.

Under the terms of the agreement, the company would underwrite the entire national debt in return for 5% interest. It was an enormous amount and one that investors could scarcely believe, but with the backing of king and Parliament, what could possibly go wrong? Soon the value of shares in the South Sea Company rose to ten times their initial value, and it seemed as though everyone, from the lord in his manor to the tradesman in his corner shop, was buying up stock.

Under the terms of the agreement, the company would underwrite the entire national debt in return for 5% interest. It was an enormous amount and one that investors could scarcely believe, but with the backing of king and Parliament, what could possibly go wrong? Soon the value of shares in the South Sea Company rose to ten times their initial value, and it seemed as though everyone, from the lord in his manor to the tradesman in his corner shop, was buying up stock.

And for the con-men, it was a dream come true.

Those with little experience in dealing with the stock market were easy prey to charlatans, and soon there was a brisk trade in companies that never even existed or were fanciful at best. Yet it was soon apparent that investors in the genuine South Sea Company weren’t much better off, and as the king gadded about Hanover in 1720, the company directors attempted to sneakily sell off their own stock. Once their investors realised that the value of the stocks was about to plummet, they joined the clamour to sell, until the stocks were worth nothing.

The collapse

Fortunes were lost, and George I headed home to England. Allegations of corruption were rampant, and in the face of accusations of bribery the Postmaster-General, James Craggs the Elder, apparently took his own life. The collapse of the market brought with it a rash of suicides and bankruptcies, and across both Houses of Parliament, hundreds were left in dire straits.

The king was heckled in the streets, and it was left to Walpole to ride to the rescue. His decisive actions in Parliament placed the meltdown under control, narrowly avoiding a complete collapse of the banks. Walpole didn’t punish everyone who was responsible though, well aware that it can be useful to have influential movers and shakers in your debt.

For commentators and satirists, the affair was a bitter gift, and Jonathan Swift famously composed The Bubble, a furious poetic swipe at the men who led the catastrophe:

Directors, thrown into the sea,

Recover strength and vigour there;

But may be tamed another way,

Suspended for a while in air.

Meanwhile Earl Stanhope, the former First Lord of the Treasury who shouldered much of the blame for the affair, finally succumbed to the pressure on the floor of the house in 1721. He was forced to abandon a debate thanks to a violent headache and was killed by a fatal stroke on the following day. His supporters blamed his passionate debating skills for his death though in fact, it might be to do with the fact that he had spent the preceding thirteen hours drinking a cocktail of champagne and liqueurs!

The South Sea Bubble had very definitely burst, and the damage to George’s reputation was done. In the wake of the catastrophe he came to rely on Walpole more than ever in Parliament, whilst Melusine was a constant comfort in matters intimate and domestic. Perhaps, though, he might not be quite so keen to take her advice when it came to stocks and shares…

Bibliography

- Belsham, W. Memoirs of the Kings of Great Britain of the House of Brunswic-Luneburg, Vol I. London: C Dilly, 1793.

- Black, Jeremy. The Hanoverians: The History of a Dynasty. London: Hambledon and London, 2007.

- Clarke, John, Godwin Ridley, Jasper and Fraser, Antonia. The Houses of Hanover & Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Coxe, William. Memoirs of the Life and Administration of Robert Walpole. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1816.

- Inglis, Lucy. Georgian London: Into the Streets. London: Viking, 2013.

- Pearce, Edward. The Great Man: Sir Robert Walpole: Scoundrel, Genius and Britain’s First Prime Minister. London: Random House, 2011.

- Saussure, Cesar de. A Foreign View of England in the Reigns of George I & George II. London: John Murray, 1902.

- Shawe-Taylor, Desmond and Burchard, Wolf. The First Georgians: Art and Monarchy 1714-1760. London: Royal Collection Trust, 2014.

- Swift, Jonathan and Hawkesworth, John. Letters, Written by Jonathan Swift: Vol III. London: A Pope, 1737.

****

A big thanks to Catherine Curzon. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Kings of Georgian Britain to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Catherine Curzon. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Kings of Georgian Britain to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Rele-vant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.