Read Part 1 of Susanne Alleyn’s post here.

*****

Carnage

In the midst of the Terror in 1794, why, consumed by guilt, didn’t executioner Charles-Henri Sanson simply quit his job and honorably retire, as he did do a year later, well after the Terror had ended?

The easy answer was that, as he himself seemed to believe, he had grown hardened to horrors by decades in the profession—or that if he had given up his title, he would have found no other work or income elsewhere. And during the Terror, the revolutionary government found it all too convenient to “forget” to pay a civil servant who had no choice but to stay in his job. If Sanson had quit, he would have had neither a job nor any hopes of reclaiming his back pay.

But I felt that the answer was not that easy. The honorable and conscientious Charles Sanson I had come to know through his diary and through others’ opinions of him—the Charles Sanson whose obvious shame and self-loathing during the worst of the Terror was making him physically ill—would have been guided by something far more than a desire to recover his back wages.

“The Gentleness Must Remain”

I had already often considered these issues when I read British hangman Albert Pierrepoint’s autobiography and discovered statements in it that explained his own attitude toward his role in the twentieth-century British system of capital punishment. The British prided themselves on making judicial hanging a decorous, humane, quite painless procedure, streamlined to reduce the duration of the actual process—from condemned cell to noose and drop—to no more than twenty seconds. Pierrepoint took this swift process to its height, usually managing to trim the time down to eight or ten seconds while offering a reassuring word or two, if necessary, to the prisoner. To Pierrepoint, his hangman’s craft was about professional detachment and expertise, always “getting it right” and getting it over with quickly so that the victim didn’t suffer mentally or physically—and this attitude, he stated, was always combined with respect toward the victim, even after death.

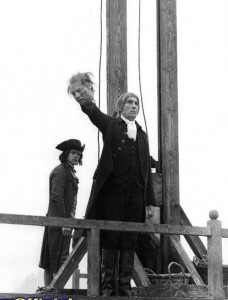

Albert Pierrepoint, probably 1950s

Albert Pierrepoint, probably 1950s

“As the executioner,” Pierrepoint wrote, “it has fallen to me to make the last confrontation with all the condemned. . . . And it is at that moment, with their eyes on mine . . . that I have known that any previous emotional involvement I may have had with them [from reading about the criminal case in the newspapers] is to be regretted. There is only a final relationship which matters: in Christianity this is my brother or sister to whom something dreadful must be done, and I have tried always to be gentle with them, and to give them what dignity I could in their death.”

Later in his autobiography he added: “I have gone on record and been many times quoted with apparent irony as saying that my job was sacred to me. That sanctity must be most apparent at the hour of death. A condemned prisoner is entrusted to me, after decisions have been made which I cannot alter. He is a man, she is a woman, who, the Church says, still merits some mercy. The supreme mercy I can extend to them is to give them and sustain in them their dignity in dying and in death. The gentleness must remain.”

Pierrepoint’s views on his “craft”—which clearly became very important to him as a task he could perform swiftly and expertly every time—exactly represented how I thought Charles Sanson had managed to cope with his always distasteful and sometimes horrible duties. During the ancien régime when criminal justice was often subjective and brutal, and even during the Terror, he must have relied on maintaining the same professional detachment, mingled with compassion, toward the condemned as Albert Pierrepoint would exhibit a century and a half later. And I came to the conclusion that Sanson, in the end, remained in his position as public executioner throughout the Terror because he, just like Pierrepoint, felt it was his duty—not to the law but to the victims, and even more so if they were the victims of injustice.

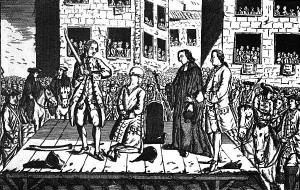

Pierre-Antoine Demachy, Une exécution capitale, place de la Révolution, detail (1793). The master executioner, respectably dressed in a cutaway coat, knee breeches, and white stockings—presumably Charles Sanson, or one of his brothers, who sometimes filled in for him—is at far right on the scaffold.

Pierre-Antoine Demachy, Une exécution capitale, place de la Révolution, detail (1793). The master executioner, respectably dressed in a cutaway coat, knee breeches, and white stockings—presumably Charles Sanson, or one of his brothers, who sometimes filled in for him—is at far right on the scaffold.

Sanson could not save the men and women—whether guilty or innocent—whom he was ordered to execute by both royal and revolutionary authorities, any more than Pierrepoint, by refusing to carry out an execution, could have saved a prisoner sentenced to death for a murder he or she might not have committed. Sanson knew that if he resigned his title, another of France’s many professional executioners would have swiftly taken his coveted place, and that the newcomer might not have been as considerate as he toward the dying. And because he could not save the victims, he must have felt strongly that it was, at the very least, his lifelong duty to offer them some final kindnesses: to carry out any last wishes; to be sure that the guillotine always worked without a hitch; to ensure that his assistants always treated the condemned with respect; to keep their last hours or moments from being any more dreadful than they had to be.

“I see [the condemned prisoner] as a person who has a fixed and stony path decreed before him from which I cannot divert him, and therefore all I can do is to help him tread it as gently as possible.”

The words are Pierrepoint’s, but they could just as easily have been Charles Sanson’s.

*****

A big thanks to Susanne Alleyn. Remember, she’ll give away three electronic copies of The Executioner’s Heir to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Susanne Alleyn. Remember, she’ll give away three electronic copies of The Executioner’s Heir to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Saturday at 6 p.m. ET.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.