Relevant History welcomes back Jeri Westerson, author of the Crispin Guest Medieval Noir novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards, from the Agatha to the Shamus. For her debut urban fantasy series, Booke of the Hidden, Publishers Weekly said, “Readers sad about the ending of Charlaine Harris’s “Midnight, Texas” trilogy will find some consolation in Moody Bog.” The next in the series, Deadly Rising, releases in October. Jeri is twice former president of SoCalMWA and OC SinC, and former vice president of SinC-LA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Relevant History welcomes back Jeri Westerson, author of the Crispin Guest Medieval Noir novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards, from the Agatha to the Shamus. For her debut urban fantasy series, Booke of the Hidden, Publishers Weekly said, “Readers sad about the ending of Charlaine Harris’s “Midnight, Texas” trilogy will find some consolation in Moody Bog.” The next in the series, Deadly Rising, releases in October. Jeri is twice former president of SoCalMWA and OC SinC, and former vice president of SinC-LA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

*****

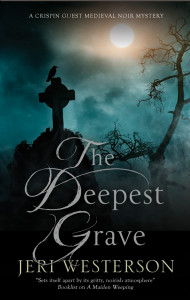

In my latest Crispin Guest Medieval Noir, called The Deepest Grave, my disgraced knight turned detective Crispin and his apprentice Jack, are called upon to investigate the graveyard of a nearby church where the priest claims that he has seen the dead walk. In the book, Crispin speaks of “Revenants” from the Latin, meaning “the returned” specifically from the dead, which implies both vampires and zombies.

Hunting a vampire isn’t easy

Let’s look at some of the historical roots of vamps first. The dead have been walking a long time. Since even before biblical accounts. Long before Bram Stoker penned his bestseller in 1897. Matthew Beresford, author of From Demons to Dracula: The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth, notes, “There are clear foundations for the vampire in the ancient world, and it is impossible to prove when the myth first arose. There are suggestions that the vampire was born out of sorcery in ancient Egypt, a demon summoned into this world from some other.” You’ll find the idea of vampires all around the world: Asian vampires, such as the Chinese jiangshi, evil spirits that attack people and drain their life energy; the blood-drinking wrathful deities that appear in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, and from ancient Egypt.

Some vampires are said to be able to turn into bats or wolves; others can’t. Some are said not to cast a reflection, others do. Holy water and sunlight are said to repel or kill some vampires, but not others. The one universal characteristic is the draining of blood.

Hunting a vampire isn’t easy. According to one Romanian legend you’ll need a seven-year-old boy and a white horse. The boy should be dressed in white, placed on the horse, and then both set loose in a graveyard at midday. Watch the horse wander around, and wherever the horse stops, that’s a vampire’s grave. Or…there’s just really good grass there.

In Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality, folklorist Paul Barber noted that centuries ago, “Often potential revenants can be identified at birth, usually by some defect, like when a child is born with teeth. Or with an extra nipple (in Romania); or a lack of cartilage in the nose, or a split lower lip (in Russia).

The belief in vampires stems from superstition and mistaken assumptions about postmortem decay. The first recorded accounts of vampires follow a consistent pattern. Some unexplained misfortune befalls a person, family or town—a drought, disease—and then it’s blamed on a vampire.

The solution? Graves were unearthed, and surprised villagers often mistook ordinary decomposition processes for supernatural phenomenon. They assumed that a body would decompose immediately, but if the coffin is well sealed and buried in winter, putrefaction might be delayed by weeks or months; the body shrinks, making it look as if the nails and hair continue to grow. And weirdest of all to medieval people, intestinal decomposition creates bloating which can force blood up into the mouth, making it look like a dead body has recently sucked blood. In certain eastern block countries, they still believe this.

Many people in medieval England thought that corpses of evil or vengeful individuals were capable of “reanimating” in the ground and then rising from their graves to attack or harm or even kill the living. Historical accounts from Britain, Ireland, and Scotland tell of fear of revenants and blood-sucking.

A 12th-century Yorkshire cleric, William of Newburgh, described an evil man, who, escaping from justice, fled the city of York, but then died and rose from his grave. Pursued by a pack of barking dogs, he wandered through courtyards and houses while everyone locked their doors. Finally, the townspeople decided to put an end to the threat by digging up his dead body, mutilating it and burning it. This is Newburgh’s account of what happened when the townspeople opened the grave:

A 12th-century Yorkshire cleric, William of Newburgh, described an evil man, who, escaping from justice, fled the city of York, but then died and rose from his grave. Pursued by a pack of barking dogs, he wandered through courtyards and houses while everyone locked their doors. Finally, the townspeople decided to put an end to the threat by digging up his dead body, mutilating it and burning it. This is Newburgh’s account of what happened when the townspeople opened the grave:

[They] laid bare the corpse, swollen to an enormous corpulence, with its countenance beyond measure turgid and suffused with blood. The young men, however, spurred on by wrath, feared not, and inflicted a wound upon the senseless carcass, out of which incontinently flowed such a stream of blood, that it might have been taken for a leech filled with the blood of many persons…

Zombies in long-deserted medieval Yorkshire village

Now—on to zombies. They are very closely related and can just as easily be called “revenants” as well. We see an emergence in our popular culture of zombies, but it originated from Haitian/African folklore, with the word “Zombi” being of West African origin. A witch doctor turns dead and living people into zombies. The belief in zombies in Haiti and certain places in Africa still persists today, the belief in either reanimating the dead or controlling living people to do their bidding in a perpetually dazed state.

Bringing it back to Europe, scientists from the University of Southampton completed a study of human bones from a long-deserted medieval Yorkshire village, Wharram Percy, and the study strongly suggests that they were from individuals regarded by their peers as revenants. The scientific analysis revealed that the individuals’ skeletal remains had been deliberately mutilated, decapitated and burned shortly after death. It is the first time in Britain that such skeletal evidence of a probable medieval belief in revenancy has been found. The work in Wharram Percy carried out on 11th- to 13th-century human bones is particularly important because it appears to confirm historical accounts of such beliefs.

There have been other skeletons found in eastern Europe with stones embedded in the mouths of the corpse, presumably to keep them from wandering. I guess it worked, because the bodies were still there.

There have been other skeletons found in eastern Europe with stones embedded in the mouths of the corpse, presumably to keep them from wandering. I guess it worked, because the bodies were still there.

Crispin and Jack must put aside their fears and superstitions to find out what’s really happening in the graveyard of St. Modwen’s parish and solve two murders before an innocent child hangs for the crime.

*****

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson!

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson!

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.