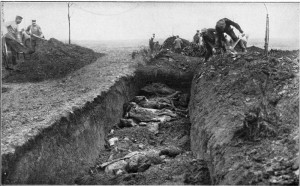

Throughout history, reports about the costs of war in terms of human lives have focused on dead and injured combatants. Commanding officers reported on the numbers of their men killed in battle, those who died afterwards as a result of their injuries, and those who were permanently injured. Pictures like this one depicting a mass grave from World War I show up in high school history books. They reinforce an erroneous assumption that the costs of war have revolved around people enlisted in regular units and militias.

Throughout history, reports about the costs of war in terms of human lives have focused on dead and injured combatants. Commanding officers reported on the numbers of their men killed in battle, those who died afterwards as a result of their injuries, and those who were permanently injured. Pictures like this one depicting a mass grave from World War I show up in high school history books. They reinforce an erroneous assumption that the costs of war have revolved around people enlisted in regular units and militias.

War doesn’t affect only combatants. Casualty reports omit or trivialize the devastation war brings to civilians. Because the physiological and psychological damage to these people hasn’t been reported, it hasn’t been quantified. Thus the cost of human warfare throughout history has been greatly understated.

Examples of military actions with costs that haven’t been quantified

The business of soldiers is combat. Historically, civilian contractors have traveled with military units to provide goods and services not covered by soldiers: goods such as tobacco, and services such as blacksmithing. Because “camp followers” often traveled with the baggage train, which was loaded with supplies, numerous accounts of battles report the accidental involvement of these civilians in actual combat. Although many of them were armed, they often proved to be a trivial challenge to trained combatants. My book Camp Follower fictionalizes this scenario at the Revolutionary War Battle of the Cowpens, 17 January 1781, in South Carolina.

Wives of soldiers have often followed the drum alongside their husbands, bringing their children with them. These civilians have landed in horrific danger. During the American Revolution, the 1 September 1777 issue of The New-York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury reported such an incident. During Sullivan’s attack on Staten Island, 22 August, loyalist commander Lt. Col. Edward Vaughan Dongan was retreating with some of his men, along with his wife and children. Discipline among Sullivan’s Continental soldiers collapsed to plundering. They chased down Dongan’s wife, and her three-year-old son witnessed her rape by Continental soldiers. Meanwhile, Dongan himself was killed. Traumatized by his mother’s rape and father’s death, the young boy died.

As his death shows, a casualty of war doesn’t always have to be a person who is physically injured or killed in a military action. Furthermore, even civilians in their homes or places of business can be traumatized by warfare. Revolutionary Reminiscences from the “Cape Fear Sketches” documents an eyewitness account from the North Carolina backcountry during the first week of April 1781. Here’s what a patriot man saw when he entered Alexander Rouse’s tavern right after the departure of redcoats who’d gunned down several of his comrades within:

Upon entering the house what a scene presented itself! The floor covered with dead bodies & almost swimming in blood, & battered brains smoking on the walls; In the fire place sat shivering over a few coals, an aged woman surrounded by several small children, who were clinging to her body, petrified with terror. We spoke to her, but she knew us not, tho familiar acquaintences; staring wildly around, and uttering a few incoherent sentences, she pointed at the dead bodies; reason had left its throne.

Unlike the Dongans’ story, we don’t know the names of the woman and children who witnessed “the Rouse House Massacre.” Most of the time, civilian casualties of war go unnamed. So when I fictionalized this aggression in my book A Hostage to Heritage, I personalized these people by giving them names.

Civilians who are exposed to combat demonstrate the kinds of immediate psychological traumas detailed in this account. Lasting psychological damage is another cost of war, even more difficult to quantify than the loss of life or visible physiological injury.

Civilians who are exposed to combat demonstrate the kinds of immediate psychological traumas detailed in this account. Lasting psychological damage is another cost of war, even more difficult to quantify than the loss of life or visible physiological injury.

In the 18th century, with no psychologists and few sedatives, do you suppose the civilians who survived the attack on the baggage train at Cowpens, or Mrs. Dongan on Staten Island, or the woman and children at Rouse’s Tavern ever ceased having post-traumatic stress disorder? What do you think were the costs to their society? And what are the costs to society today from similar activity in war-torn countries all over the world?

#PTSD in civilians during the #AmRev http://bit.ly/1fVzAoH #history via @Suzanne_Adair

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.