Relevant History welcomes back Anna Castle, who writes the Francis Bacon mysteries and the Lost Hat, Texas mysteries. She’s earned a series of degrees—BA Classics, MS Computer Science, and PhD Linguistics—and has had a corresponding series of careers—waitressing, software engineering, assistant professor, and archivist. Writing fiction combines her lifelong love of stories and learning. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and follow her on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes back Anna Castle, who writes the Francis Bacon mysteries and the Lost Hat, Texas mysteries. She’s earned a series of degrees—BA Classics, MS Computer Science, and PhD Linguistics—and has had a corresponding series of careers—waitressing, software engineering, assistant professor, and archivist. Writing fiction combines her lifelong love of stories and learning. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site and follow her on Facebook.

*****

Many of us traveled over the last Christmas holidays, heading out in trains, planes, and automobiles to visit friends and family. December isn’t the best season for travel in the northern hemisphere. Snow falls and wind blows, even across the southern tier. Still, all in all, we expect to get where we’re going in a day or two under fairly predictable circumstances.

Let’s travel back four centuries to Elizabethan England. Many people journeyed home from the capitol to spend the holidays with their families, like the gentlemen of the Inns of Court, who only came to town when the courts were in session.

Horse or carriage?

Your options for transport were horse or shank’s mare (foot). Coaches appeared in England in the 1590s, but they were only for the wealthy and chiefly used inside the metropolis. Men like Sir Horatio Palavicino and Anthony Bacon, both of whom suffered terribly from gout, traveled by coach, but neither traveled far. Anthony once tried to get from Twickenham to Windsor to answer an invitation from the queen, but was forced to cut his journey short at Colnbrook, about six miles away. The coaches must have been dismally uncomfortable.

Most barristers would have ridden their own horses with their own handmade saddles and a servant or two to carry their packs and keep them company. Women traveled on horseback as well. They could choose to ride astride or sidesaddle. The sidesaddle was improved by Catherine de Medici in the sixteenth century, making it easier for women to control their mounts and thus ride independently.

Most barristers would have ridden their own horses with their own handmade saddles and a servant or two to carry their packs and keep them company. Women traveled on horseback as well. They could choose to ride astride or sidesaddle. The sidesaddle was improved by Catherine de Medici in the sixteenth century, making it easier for women to control their mounts and thus ride independently.

Lesser folks walked when they needed to get from one place to another. I love to imagine Christopher Marlowe loping along with his rangy stride from Canterbury to Cambridge. As a cobbler’s son, he wouldn’t have owned a horse. University scholarships didn’t run to that level of luxury. Still, he was young and healthy and would easily have found companions on those well-traveled roads.

Are we there yet?

A horse walks at 3–4 miles per hour and trots at 8–10. 2–3 mph is normal for a person walking. Your servants could comfortably walk alongside your horse. Twenty miles a day—ten there and ten back—was typical on a market day. This is why towns in places like England (settled before horses and carriages became common) tend to be about ten miles apart.

Twenty miles a day would make a good day of travel, whatever your mode of transportation. This delightful tool will draw a twenty-mile radius around any location you please. Francis Bacon could reach his mother’s house in Gorhambury, near St. Albans, in one day—if it weren’t for his hemorrhoids, which frequently drove him back to his chambers at Gray’s Inn.

A person on horseback with reason to hurry could travel 30–40 miles in a day, but then he’d have to change horses to go further. Robert Carey famously rode from London to Edinburgh in just under three days, to deliver the news that Queen Elizabeth had died.

Lost and found

I’ve gotten lost two miles from a major road in England, or rather I’ve reached forks in the road between which I could not choose and been forced to turn back. I once went rambling with a group of experienced hikers, equipped with maps and GPS apps, and stood waiting while these gadget-minded men debated the correct turn to take. It’s amazing how quickly landmarks disappear behind trees or gentle hills.

Unless you knew your road and knew it well, you would need a guide. Major roads, like those used by the nascent royal postal service, might be clear enough to get from town to town with minor assistance at crossroads. Major roads ran between Dover and London, London to Edinburgh, and Canterbury to Oxford (among other routes.) In December, these major thoroughfares would be muddy and badly rutted. To venture farther afield, you’d have to rely on locals for directions and hope they gave you good information.

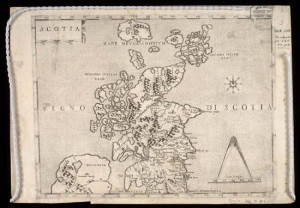

There were maps aplenty in those days—map-making was a booming craft—but they weren’t meant to aid travelers on land. Maps of coastlines, made by sailors, were amazingly good, but interior spaces were not often well represented. The Tudors were just beginning to get England’s roads organized into some kind of system. This map gives you an overall sense of Scotland’s topography, but it won’t get you from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

There were maps aplenty in those days—map-making was a booming craft—but they weren’t meant to aid travelers on land. Maps of coastlines, made by sailors, were amazingly good, but interior spaces were not often well represented. The Tudors were just beginning to get England’s roads organized into some kind of system. This map gives you an overall sense of Scotland’s topography, but it won’t get you from Glasgow to Edinburgh.

In 1586, Michaelmas (autumn) term ended on 3 December. The courts re-opened for Hilary term on 12 January. That gave you a little less than six weeks vacation. If you lived in the north, in someplace like Lancashire, it might take you ten days to get home. Another ten to ride back and you’ve barely had time to kiss your wife and watch your children open their New Year’s gifts. At least you wouldn’t be stranded in an airport!

*****

A big thanks to Anna Castle. She’ll give away an ebook or autographed paperback copy of The Widows Guild, her third Francis bacon mystery, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide for the ebook and the U.S. only for the paperback.

A big thanks to Anna Castle. She’ll give away an ebook or autographed paperback copy of The Widows Guild, her third Francis bacon mystery, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide for the ebook and the U.S. only for the paperback.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.