Relevant History welcomes back L.A. native Jeri Westerson, who combined the medieval with the hard-boiled and came up with her own brand of medieval mystery she calls “Medieval Noir.” Her brooding protagonist, Crispin Guest, is a disgraced knight turned detective on the mean streets of fourteenth century London. Jeri’s novels have been shortlisted for a variety of industry awards, from the Agatha to the Shamus. She is president of the Southern California chapter of Mystery Writers of America, and speaks all over the southland about medieval history, including as a guest lecturer at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana and Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, CA. To learn more about Jeri’s books, watch a series book trailer, find discussion guides, and read Crispin’s blog, check out Jeri’s website. Friend Jeri on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes back L.A. native Jeri Westerson, who combined the medieval with the hard-boiled and came up with her own brand of medieval mystery she calls “Medieval Noir.” Her brooding protagonist, Crispin Guest, is a disgraced knight turned detective on the mean streets of fourteenth century London. Jeri’s novels have been shortlisted for a variety of industry awards, from the Agatha to the Shamus. She is president of the Southern California chapter of Mystery Writers of America, and speaks all over the southland about medieval history, including as a guest lecturer at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana and Mt. San Antonio College in Walnut, CA. To learn more about Jeri’s books, watch a series book trailer, find discussion guides, and read Crispin’s blog, check out Jeri’s website. Friend Jeri on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter and Goodreads.

*****

My medieval mysteries always involve a religious relic or venerated object. And so part of my job is to explore relics and make the mythical real. Some of my “favorite” relics (in that they get a lot of attention) are the blood relics. My protagonist Crispin Guest, a disgraced knight turned detective, has a favorite oath: “God’s blood!” Yes, in the medieval period, swearing took on a whole different quality. But it is “God’s blood” and that of his saints that we want to explore.

Holy grail, Batman!

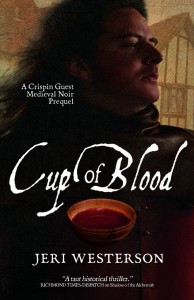

Joseph of Arimathea plays an important role in most Christ blood relics, either capturing the blood and sweat in a cup while Jesus hung on the cross (and here is where the complicated grail history begins and what we see in Cup of Blood, my latest medieval mystery, released 25 July 2014) or later keeping some as he cleaned the body before burial.

I must first explain the unlikelihood of such an event from the Jewish Pharisee that Joseph was. Surely he was aware of the blood prohibitions, of touching blood and bodies that would make him unclean to enter the temple. This would be a horrific situation for a priest of the temple, his being unable to enter it until he underwent many days of ritual bathing before he was declared clean again. The thought of even saving blood must have been completely foreign. But let us, for the sake of argument, assume that Joseph—for whatever reason—had the idea to preserve some of Jesus’ blood. What did he do with it from there?

If we were to follow the grail legend, then we would end up at Glastonbury in the southwest region of England, which gave rise to its co-mingling with the Arthurian legends (a complicated cross-pollination from the stories commissioned by Marie of France, Countess of Champagne and daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine in the twelfth century to include a love triangle. She had Chretien de Troyes, her court poet, invent Lancelot. Chretien also wrote the unfinished poem Perceval le Gallois, the keeper of the grail—and it only gets more convoluted from there).

If we were to follow the grail legend, then we would end up at Glastonbury in the southwest region of England, which gave rise to its co-mingling with the Arthurian legends (a complicated cross-pollination from the stories commissioned by Marie of France, Countess of Champagne and daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine in the twelfth century to include a love triangle. She had Chretien de Troyes, her court poet, invent Lancelot. Chretien also wrote the unfinished poem Perceval le Gallois, the keeper of the grail—and it only gets more convoluted from there).

The bloodier the better

But if we were to follow other blood legends, we might end up in Constantinople. During the fourth crusade it is said that the Holy Blood of Christ made its way from Constantinople to the Basilius chapel in Bruges on 7 April 1150. The relic consists of coagulated blood kept in a 12th century style rock-crystal flask. Since 1303, the relic was carried around the city walls in procession, called the Holy Blood Procession, which is still celebrated today.

But if we were to follow other blood legends, we might end up in Constantinople. During the fourth crusade it is said that the Holy Blood of Christ made its way from Constantinople to the Basilius chapel in Bruges on 7 April 1150. The relic consists of coagulated blood kept in a 12th century style rock-crystal flask. Since 1303, the relic was carried around the city walls in procession, called the Holy Blood Procession, which is still celebrated today.

Westminster Abbey was presented with Christ’s blood by King Henry III of England on 3 October 1247, that the king had received from the Masters of the Knights Templars and Hospitallers and the patriarch of Jerusalem. It was encased in a crystal vase. The Bishop of Norwich preached a sermon, promising an indulgence of six years and one hundred and sixteen days to anyone who venerated the relic (that is, six years and one hundred and sixteen days less in Purgatory). Unfortunately, it never made Westminster the pilgrim stop that Henry had desired. In fact, it was not lost on the populace that Henry was desperately trying to compete with the French king who a year later, dedicated his Sainte Chapelle with relics from the holy land, among them the Crown of Thorns, the Holy Lance, a portion of the sponge soaked with vinegar, purple vestments with which Jesus was mocked, and a sepulchral stone. In Hailes Abbey, not too far from Westminster, larger crowds came to see their vial of Christ’s blood. But when Hailes’ blood was scrutinized in the 16th century by Henry VIII’s examiners, it was reported that the vial consisted of not Christ’s blood but of honey mixed with saffron coloring. Yet another account says it contained oft-replaced goose blood. Whatever was in it, this vial, along with the one at Westminster, was disposed of by the Reformation’s agents.

Bleeding out

One of the more famous blood relics belongs to Saint Januarius or as he is known in Italy, San Gennaro. Born in Naples in 300 AD, he was a Bishop of Beneveto around the time of Emperor Diocletian, who was particularly nasty to Christians. While offering spiritual support to imprisoned fellow Christians, Januarius was himself arrested. The prelate, Timoteo, put Januarius through several gruesome tortures—thrown into a furnace, tried to tear his limbs apart on the wheel—but he seemed to come out of them unscathed. Finally, Januarius and his fellow prisoners were condemned to be torn apart by wild beasts. When this also proved useless, Timoteo ordered Januarius to be beheaded.

One of the more famous blood relics belongs to Saint Januarius or as he is known in Italy, San Gennaro. Born in Naples in 300 AD, he was a Bishop of Beneveto around the time of Emperor Diocletian, who was particularly nasty to Christians. While offering spiritual support to imprisoned fellow Christians, Januarius was himself arrested. The prelate, Timoteo, put Januarius through several gruesome tortures—thrown into a furnace, tried to tear his limbs apart on the wheel—but he seemed to come out of them unscathed. Finally, Januarius and his fellow prisoners were condemned to be torn apart by wild beasts. When this also proved useless, Timoteo ordered Januarius to be beheaded.

Januarius’ old wet-nurse Eusebia, gathered his blood into vials, and his body and head were wrapped and hidden until the time that Christianity was no longer persecuted. Eusebia was now free to display the glass vials of the martyr’s dried blood, and for the first time, they became liquid. Januarius was one of the many honored saints in Italy for many centuries, but there is no mention of his blood or it’s “liquefaction” until 1389. By then his skull and blood had come to rest at the Real Cappella del Tesoro di San Gennaro, located near Pozzuoli. And to this day, on 19 September, the feast day of Saint Januarius, his blood relics are displayed with much praying, novenas, and other celebrations. If the blood liquefies, it is signaled by the firing off of cannons.

Certainly in Crispin’s era of the late fourteenth century, such things were well venerated. And much money could be made for the church or monastery that housed such a relic, paid by the pilgrims who came to see them. No wonder my detective remains skeptical as to the authenticity of such objects. And that, and a few murders, keeps him embroiled deeply in the mysteries.

*****

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of Cup of Blood to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of Cup of Blood to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.