Relevant History welcomes Libi Astaire, author of the Ezra Melamed historical mystery series set in Regency England. The series has received accolades from the Jewish Book Council, and the first book, The Disappearing Dowry, received a Sydney Taylor Notable Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries. To find out more about the series, or to read an excerpt from the latest mystery, The Doppelganger’s Dance, check Libi’s web site and look for her on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes Libi Astaire, author of the Ezra Melamed historical mystery series set in Regency England. The series has received accolades from the Jewish Book Council, and the first book, The Disappearing Dowry, received a Sydney Taylor Notable Book Award from the Association of Jewish Libraries. To find out more about the series, or to read an excerpt from the latest mystery, The Doppelganger’s Dance, check Libi’s web site and look for her on Facebook.

*****

When I was young, one of my favorite Broadway musicals was Bye Bye Birdie, the show that chronicles the excitement of a small Midwestern town when a rock and roll star comes to visit. What does rock and roll have to do with Regency England? Not much at first glance. But I did think of Bye Bye Birdie the first time I came across an account of a visit that set Regency London’s Jewish community all aflutter.

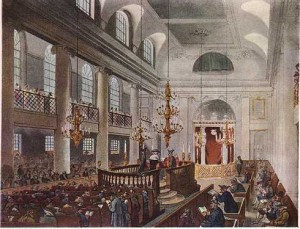

On the night of Friday 14 April 1809, three of England’s Royal Dukes—the Dukes of Cumberland, Sussex and Cambridge—attended the Sabbath Evening Services at London’s Great Synagogue, which was the central place of worship for England’s Ashkenazic community. This wasn’t the first time that a member of the Royal Family had visited a London synagogue, but such an honor was a rare occurrence. The fact that there would be three of them—and at a time when the Emancipation of the Jews was being hotly discussed in drawing rooms and coffee houses throughout England—was enough to send the small community into a whirlwind of frenetic activity as they made their preparations to welcome these influential visitors.

On the night of Friday 14 April 1809, three of England’s Royal Dukes—the Dukes of Cumberland, Sussex and Cambridge—attended the Sabbath Evening Services at London’s Great Synagogue, which was the central place of worship for England’s Ashkenazic community. This wasn’t the first time that a member of the Royal Family had visited a London synagogue, but such an honor was a rare occurrence. The fact that there would be three of them—and at a time when the Emancipation of the Jews was being hotly discussed in drawing rooms and coffee houses throughout England—was enough to send the small community into a whirlwind of frenetic activity as they made their preparations to welcome these influential visitors.

A Royal Welcome

The first time around, Jews didn’t do so well in Britain. William the Conqueror invited Jewish merchants from the Continent to settle in England, since he needed someone to act as his financiers, but the Jews were expelled from the country in 1290 by King Edward I.

Although there was a small group of crypto-Jews from Spain and Portugal living in England during Shakespeare’s time (I wrote about these refugees from the Spanish Inquisition in my novel The Banished Heart), Jews weren’t allowed to live openly as Jews until the 1650s, when Oliver Cromwell famously decided not to decide if Jews should be allowed back into England or not. Thanks to that loophole, the second chapter of Anglo-Jewish history began.

Some of the Jews who arrived in the late 1600s and 1700s were descendants of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492. These wealthy Sephardic Jewish merchants (Sepharad is the Hebrew word for Spain) had extensive trade connections that made them welcome not only at Cromwell’s palace, but at the royal courts of Charles II and William III.

There was also a sizeable community of Ashkenazic Jews who came from countries such as Germany (Ashkenaz in Hebrew), Bohemia, Holland and even faraway Poland. Although there were some wealthy merchants among their ranks, the Ashkenazic community was mainly comprised of poor Jews escaping the religious persecution that was prevalent on the European Continent.

Not all Englishmen welcomed this influx of foreigners. Indeed, the newcomers faced barriers in just about every sphere. Foreign-born Jews, the majority of the community until the early 1800s, couldn’t own property or engage in foreign trade unless they could afford to pay special taxes. No Jew could become a Member of Parliament, attend an English university or become an officer in the army or navy. Jews couldn’t open a retail business within the area that comprised the ancient City of London. They also couldn’t vote—although that was a privilege denied to many Englishmen and all women. In fact, one reason why some Englishmen were so against Jewish Emancipation was because they feared it would lead to all Englishmen being allowed to vote. (They couldn’t imagine that women would ever demand and get that right.)

Still, England was a tolerant haven in comparison to Europe. And during the Georgian era (1714–1830) the Jews found they had friends in English society, including some in very high places.

A Loyal Response

The royal visit to the Great Synagogue was arranged by Abraham Goldsmid, a wealthy Jewish financier who was friends with several members of the Royal Family, including the Duke of Sussex (Prince Frederick Augustus) and the Duke of Cambridge (Prince Adolphus Frederick).

Although the members of the Great Synagogue had only two weeks to prepare, according to press reports they did admirably. A welcoming service comprised of poems and songs was hastily put together. England’s chief rabbi, Rabbi Solomon Hirschell, was garbed in an elegant white satin robe made especially for the occasion. The synagogue’s interior was also spruced up, thanks to the new crimson velvet curtains furnished by a rising star on the London financial scene, Nathaniel Rothschild.

Then the hour arrived—half past six—and it’s not hard to imagine the community’s excitement as the rumble of the approaching carriages grew louder. When those elegant carriages came to a halt, Jewish children dressed in their Sabbath finery were there to greet the visitors, strewing the path to the synagogue’s entrance with flowers. And when the royal entourage stepped inside the candle-lit sanctuary, they were greeted by a full choir, which sang:

Open wide the gates for the princely train

The Heav’n-blessed offspring of our King

Whilst our voices raise the emphatic strain

And God’s service devout we sing.

Of course, not everyone was pleased with this public recognition of the Jewish community. Thomas Rowlandson, one of the era’s most popular caricaturists, ridiculed the event in a satirical cartoon that very likely reflected the feelings of those against giving Jews (and Catholics) full political and civil rights.

Of course, not everyone was pleased with this public recognition of the Jewish community. Thomas Rowlandson, one of the era’s most popular caricaturists, ridiculed the event in a satirical cartoon that very likely reflected the feelings of those against giving Jews (and Catholics) full political and civil rights.

However, the royal visit is considered one of the steps along the path to the Emancipation of England’s Jews later that century. True, it was only a symbolic gesture, but it’s often the symbolic social gesture that paves the way for political and legal change. It’s therefore no wonder that this royal visit was still being enthusiastically discussed by members of the Great Synagogue for many years afterward.

It’s also a matter of pride for the fictional members of the Great Synagogue who are at the heart of my Ezra Melamed Mystery Series. They too remember that great day when the three Royal Dukes came to visit—that is, when they’re not too busy trying to solve the latest “white cravat” crime that is causing an upheaval in their community.

*****

A big thanks to Libi Astaire. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The Doppelganger’s Dance to someone who contributes a comment on her post this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

A big thanks to Libi Astaire. She’ll give away a trade paperback copy of The Doppelganger’s Dance to someone who contributes a comment on her post this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.