Relevant History welcomes historical mystery novelist I. J. Parker, who has followed the exploits of her eleventh-century Japanese detective, Akitada, in short story and novel since 1996. Her story “Akitada’s First Case” won the Shamus award in 2000. Her novels have been translated into several languages. In addition to the Akitada mysteries and stories, she has written three novels set during the Heike Wars at the end of the twelfth century, and one about eighteenth-century Germany. For more information, visit her web site.

Relevant History welcomes historical mystery novelist I. J. Parker, who has followed the exploits of her eleventh-century Japanese detective, Akitada, in short story and novel since 1996. Her story “Akitada’s First Case” won the Shamus award in 2000. Her novels have been translated into several languages. In addition to the Akitada mysteries and stories, she has written three novels set during the Heike Wars at the end of the twelfth century, and one about eighteenth-century Germany. For more information, visit her web site.

Note: the Akitada novel Death on an Autumn River will be free in Amazon Kindle format 23–26 November.

*****

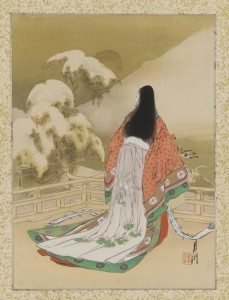

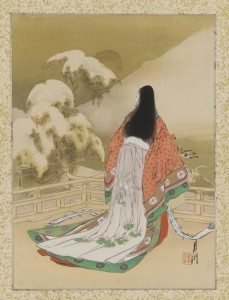

I first discovered Asian history, and more precisely that of Japan, through its literature, especially the great novel Genji, written by a court lady in the first decade of the eleventh century and thus the first novel in the world. This book astonished me by its sophistication, its understanding of the psychology of men and women, its emotional and poetic response to nature, and its probing of the human condition.

I first discovered Asian history, and more precisely that of Japan, through its literature, especially the great novel Genji, written by a court lady in the first decade of the eleventh century and thus the first novel in the world. This book astonished me by its sophistication, its understanding of the psychology of men and women, its emotional and poetic response to nature, and its probing of the human condition.

Not long after exploring Japanese literature of this period, I became interested in writing mysteries and decided to write about early Japan. I was convinced that others would also come to love this strange, wonderful, and exotic culture and discover another world while spellbound by a mystery plot.

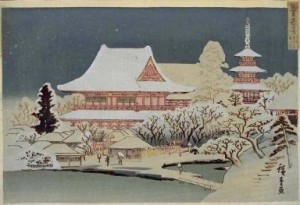

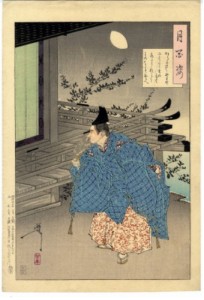

Let me caution you. Eleventh-century Japan is not the time of shoguns and samurai. Life was far more decorous then—at least on the surface. The country was still ruled by an emperor and a complex central government. Influenced by Tang China, Japan’s culture had reached its height of elegance and artistic achievement by the eleventh century. The arts flourished, and both men and women of the upper classes played musical instruments, painted, read and wrote poetry and prose in both Japanese and Chinese. They had universities, elegant palaces, huge temple complexes, exquisite gardens and parks, and whole cities neatly laid out by the ancient rules of feng shui. The upper classes dressed in silks and brocades, enjoyed games like backgammon, chess, and go, and engaged in sports like football, wrestling, archery, fishing, and hunting.

But this advanced and luxurious culture was controlled by a large, rigid bureaucracy and supported by the labors of peasants, fishermen, artisans, and merchants. Many of the common people were very poor and lived in densely-packed, rat-infested neighborhoods. Some resorted to crime in city streets and on the highways. And in distant provinces, warlords were busily building their armies. Unlike the Chinese, who took swift and brutal action against traitors and criminals, Japan’s system of law and order forbade the taking of life, and consequently criminals flourished because they could not be effectively restrained. Except for rare special cases, exile with hard labor or imprisonment were the only available punishments, and these were frequently nullified by sweeping imperial pardons.

Against this background, I conceived of men like Akitada, a civil servant representing the law, a man of honor and duty. Such men would have had their hands full, especially when crimes were committed by the privileged who could count on support from powerful men in the government. In such cases, considerable personal danger would be involved, as Akitada discovers in Rashomon Gate and in the short story “Akitada’s First Case.”

Against this background, I conceived of men like Akitada, a civil servant representing the law, a man of honor and duty. Such men would have had their hands full, especially when crimes were committed by the privileged who could count on support from powerful men in the government. In such cases, considerable personal danger would be involved, as Akitada discovers in Rashomon Gate and in the short story “Akitada’s First Case.”

Akitada is a member of the upper classes, but his family has fallen on hard times. Because he excelled at his law studies at the university, he was given a lowly position in the Ministry of Justice where his interest in “low crime” keeps him in constant hot water and gets him various punitive assignments to unpleasant places. However, this means that he makes interesting friends (like Tora, Genba, and Hitomaro) among the less privileged but more colorful members of his society. We learn from history that human beings don’t change much over the centuries or geographic distances. Basic human traits are constant, and knowing this allows us to understand the past by identifying with its people.

Akitada has taken me on many exciting adventures. We have explored Buddhist monasteries, visited the imperial palace and its surroundings, traveled to a penal colony, delved into a gold mine, and attacked a warlord’s fortress. We have been to brothels and bathhouses, shopped at markets, viewed aristocratic gardens, and roamed among professors and students at the university. The people Akitada introduces me to are princes and paupers, officials and outlaws, monks and courtesans. We have visited eleventh-century entertainers and sword smiths, wrestlers and martial arts practitioners together.

Akitada has taken me on many exciting adventures. We have explored Buddhist monasteries, visited the imperial palace and its surroundings, traveled to a penal colony, delved into a gold mine, and attacked a warlord’s fortress. We have been to brothels and bathhouses, shopped at markets, viewed aristocratic gardens, and roamed among professors and students at the university. The people Akitada introduces me to are princes and paupers, officials and outlaws, monks and courtesans. We have visited eleventh-century entertainers and sword smiths, wrestlers and martial arts practitioners together.

You may wonder how true to actual fact all these details are. I enjoy research, and have been working on this period for thirty years now. I know the scholarly and primary materials and do additional research for each new novel or story. But I write fiction, not history, and sometimes facts have to be bent to the story. I try to do as little of this as possible and add a historical note at the end of each novel to explain the background and any liberties I may have taken. For example, scholars don’t know for certain how long the famous Rashomon gate stood at the southern entrance to Kyoto, but the gate has enormous symbolic significance for early Japanese culture and is familiar to many western readers from the Japanese film by the same name. I used the gate for its historical connotations but explained the problems of dating in the end note.

In the process of our imaginary travels, I have become very fond of my protagonist. Akitada is by no means a perfect man. He is shy, introverted, stubborn, rash, and judgmental. He makes mistakes and suffers the pangs of conscience for them. But he does not rest until the wrong has been righted, even if it means risking his career, his life, or the lives of loved ones. In spite of all his flaws, he is ultimately a man of great courage and intelligence, though he is completely unaware of this. The women in his life love him and he loves them back, but he is an awkward and unintentionally insensitive partner. Akitada is a man of early eleventh-century Japan, but he is always human, I hope, and human nature does not change much over the centuries.

I look forward to future adventures and to watching him change from the naiveté of the very young man in The Dragon Scroll to a wiser, sadder, and perhaps more troubled middle age. The eleventh novel in the series, Death of a Doll Maker, was released this past summer, and there are many others waiting, I hope.

*****

A big thanks to I. J. Parker. She’ll give away one copy of an Akitada book to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Tuesday at 6 p.m. ET. Then the winner may select either Rashomon Gate in hardcover or The Hell Screen in trade paperback Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

A big thanks to I. J. Parker. She’ll give away one copy of an Akitada book to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Tuesday at 6 p.m. ET. Then the winner may select either Rashomon Gate in hardcover or The Hell Screen in trade paperback Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.