Historical fantasy/steampunk author Jeri Westerson describes the depth of historical research she used for her series.

###

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native Jeri Westerson, author of twelve Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mystery novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri also writes two paranormal series: “Booke of the Hidden,” and the “Enchanter Chronicles Trilogy,” the first of which is The Daemon Device. (Watch the trailer here.) She has served two terms as president of the Southern California Chapter of Mystery Writers of America, twice president of the Orange County Chapter of Sisters in Crime, and as vice president for the Los Angeles Chapter of Sisters in Crime. To learn more about Jeri and her books, visit her web site (plus Enchanter Chronicles), and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native Jeri Westerson, author of twelve Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mystery novels, a series nominated for thirteen national awards from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri also writes two paranormal series: “Booke of the Hidden,” and the “Enchanter Chronicles Trilogy,” the first of which is The Daemon Device. (Watch the trailer here.) She has served two terms as president of the Southern California Chapter of Mystery Writers of America, twice president of the Orange County Chapter of Sisters in Crime, and as vice president for the Los Angeles Chapter of Sisters in Crime. To learn more about Jeri and her books, visit her web site (plus Enchanter Chronicles), and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Goodreads.

*****

It’s fantasy, you say. Why does it need to be historical? Can’t you just make it all up?

Not on my watch, missy.

Since I come from a background steeped in historical research for my Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mysteries, it was natural to do the research needed for a Victorian setting for my fantasy/steampunk venture, The Daemon Device, book one in the Enchanter Chronicles Trilogy.

Having a foundation in the real history gives the magic system I’ve created a certain weight. It grounds the reader in the familiar before it branches off into its fantasy realm, a place where even fantastical machinery is powered by steam (hence the “steampunk” aspect) as well as a certain level of magic.

Steampunk is one of those “speculative fiction” sub-genres, usually tied in one way or another with a smattering of science fiction and sometimes a supernatural aspect, as well as alternate history.

My history is just a smidge “alternate” with Prince Albert surviving his brush with pneumonia to live a long life with Queen Victoria, and the fact that dirigibles are commonplace, chugging through the sooty skies of London. It’s all matter-of-fact, don’t you know. That’s just the backdrop to the fantasy part, the part with my magician, Leopold Kazsmer, the Great Enchanter, with his Jewish/Romani heritage he is none too proud of. A man who has learned through his study of the Kabbalah to summon Jewish daemons to help him perform real magic. “Daemons” as in the helpful kind as opposed to “demons”, the evil kind.

Daemons vs demons

And that, too, led to some research into what the interpretation of demons has been between the Judeo and Christian sides of scriptures. Jewish mysticism goes in some surprising directions. In Judaism, for instance, there is no Hell as Christians have defined it. No pitchfork Devil in charge of tormenting souls for all eternity. Instead, Jewish belief is that there cannot be eternal punishment for a finite life of sin. God just isn’t that vindictive. The writings talk of Gehenna—a place of waiting and working out one’s remorse for past sins (like purgatory)—and was the dwelling of the daemons. Its partner in another locale but Gehenna-adjacent is Sitra Achra, the place where all evil comes from.

And that, too, led to some research into what the interpretation of demons has been between the Judeo and Christian sides of scriptures. Jewish mysticism goes in some surprising directions. In Judaism, for instance, there is no Hell as Christians have defined it. No pitchfork Devil in charge of tormenting souls for all eternity. Instead, Jewish belief is that there cannot be eternal punishment for a finite life of sin. God just isn’t that vindictive. The writings talk of Gehenna—a place of waiting and working out one’s remorse for past sins (like purgatory)—and was the dwelling of the daemons. Its partner in another locale but Gehenna-adjacent is Sitra Achra, the place where all evil comes from.

The word “daemon” itself is a Latin version of a Greek word for benevolent spirits. It starts to get complicated from there between the Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism), the Talmud (commentary on Jewish civil and ceremonial law and legend), and translations between languages.

Mysticism meets magic

History sure gives you a choice of protagonists as well as antagonists, and plenty of real-world events to draw into your fiction, including Imperial Germany’s gearing up for the first run of the Master Race in World War I. It wasn’t hard to conjure up a Germanic order of world domination. Using dirigibles to do it? Hey, why not?

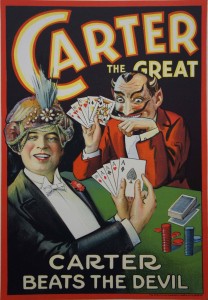

Added to that, is the world of the nineteenth century magician. If you look at some of the posters from the era, there is plenty of use of demon imagery, where even the magician Carter “Beats the Devil.”

Added to that, is the world of the nineteenth century magician. If you look at some of the posters from the era, there is plenty of use of demon imagery, where even the magician Carter “Beats the Devil.”

In the mid-1800s in the United States, Ouija Boards were coming into vogue with a huge upsurge of interest in spiritualism (possibly due to the many deaths in the American Civil War). It was touted as a wholesome activity for the whole family! And why not? If Aunt Effie kicked the bucket before you could visit her deathbed, you could always call her up on the Spirit Board and say your good-byes then. By 1891, the first few advertisements hit the papers for “Ouija, the Wonderful Talking Board.”

I’ve always been fascinated by this time period of magicians, spiritualism, ghosts, and ectoplasm, where séances and the investigation into the next world compelled and enthralled, and science was still crossed with a certain level of mysticism, where maybe magic was a real possibility. Ask Sir Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame, a séance fancier, and who was gullible enough to believe a couple of little girls took pictures of fairies in their garden.

It’s a time where anything could happen. And anything can…with a little magic.

*****

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson! She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Daemon Device to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson! She’ll give away an ebook copy of The Daemon Device to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter. And check out my Patreon, now live!

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native and award-winning author Jeri Westerson, who writes the critically acclaimed Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mysteries, historical novels, paranormal novels, and LGBT mysteries. To-date, her medieval mysteries have garnered twelve industry award nominations, from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri is the former president of the SoCal chapter of Mystery Writers of America, former vice president of Sisters in Crime Los Angeles, and frequently guest lectures on medieval history at local colleges and museums. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native and award-winning author Jeri Westerson, who writes the critically acclaimed Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mysteries, historical novels, paranormal novels, and LGBT mysteries. To-date, her medieval mysteries have garnered twelve industry award nominations, from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri is the former president of the SoCal chapter of Mystery Writers of America, former vice president of Sisters in Crime Los Angeles, and frequently guest lectures on medieval history at local colleges and museums. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away an ebook of A Maiden Weeping to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away an ebook of A Maiden Weeping to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.