Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 29 June – 5 July, I’m participating with more than two hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Relevant History welcomes Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He has written numerous articles and three books on the subject, using primary sources to reveal personal information about British soldiers and their wives in America. His fourth book, British Soldiers, American War will be released from Westholme Publishing in November 2012. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers, and his books are available from Revolutionary Imprints, also a source for first-hand accounts of the American Revolution.

Relevant History welcomes Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He has written numerous articles and three books on the subject, using primary sources to reveal personal information about British soldiers and their wives in America. His fourth book, British Soldiers, American War will be released from Westholme Publishing in November 2012. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers, and his books are available from Revolutionary Imprints, also a source for first-hand accounts of the American Revolution.

*****

John Row was a British officer in the 9th Regiment of Foot, and he was in love with Jenny Innes. For six years their courtship was maintained largely by correspondence due to separations during his military career. I recently perused dozens of their letters that survive in the National Archives of Scotland, revealing a touching love story and a surprising visual treasure.

Row began writing to Jenny from Dublin in 1775, soon after they had met. They hadn’t made their mutual interest known to her family and agreed to limit their correspondence so as not to arouse suspicions. The next year, however, saw the 32-year-old officer embarking to join the war in America, bound for “Quebec which is not the worst Country in the World.”

Row’s letters from America are not particularly informative. (A soldier in his regiment, Roger Lamb, left a detailed chronicle of the 9th Regiment’s service. Lamb later transferred to the 23rd Regiment and Cornwallis’s army, and his chronicle includes details of his military action in the Southern theater.) From Quebec, Row apologized in letter after letter for writing so frequently, since he did not know when the next opportunity would arise. A long winter in lonely isolated quarters curtained their correspondence, which resumed only briefly in the spring of 1777 before a new campaign began. In the mean time Row had received only one letter from Jenny since departing Ireland, and he feared for her health as she battled respiratory complaints.

It was Lt. Row’s own health, however, that caused the next hiatus. In November 1777 he wrote from London, informing Jenny that he had been wounded in the right knee at the Battle of Hubbardton on 7 July 1777. In Great Britain to recover, he hoped to return to his regiment in the spring. The campaign he’d left had gone badly, though, and the 9th Regiment was in captivity after the British capitulation at Saratoga. Row returned to Scotland, spent time with Jenny and negotiated with her family. This sojourn was a short one, however, as Row had his career to attend to.

There was nothing in Britain for a zealous officer determined to distinguish himself. In 1779 Row was able to obtain a captain’s commission in a new regiment, the 85th Regiment of Foot, being raised for service in the rapidly-expanding war. Jenny objected to his choice, for not only would it keep them apart but it also stood to put him at risk if the regiment was sent abroad. He nonetheless related details of his recruiting and training activities.

Within a few months the 85th Regiment was fit for service and received orders for the West Indies. Jenny was mortified and wrote a long letter expressing her dire concerns for her beloved’s fate. Hadn’t he already risked enough and suffered enough? Not only would the climate be his enemy, but he would be exposed to greater danger because the effects of his wound made him less adroit than younger officers. Having stated her misgivings, she agreed to say no more on the subject.

As the 85th was preparing to embark, a painter arrived at the port offering his services to officers who knew they might be leaving their homeland for the last time. Row commissioned a portrait for Jenny, which the artist prepared for by using a projection machine to create a silhouette. Row mailed the silhouette to Jenny on 30 March 1780, and this rare image remains enclosed in the letter to this day. Seen here, it is a fascinating look at this man who zealously sought to balance love for a lady and a career.

As the 85th was preparing to embark, a painter arrived at the port offering his services to officers who knew they might be leaving their homeland for the last time. Row commissioned a portrait for Jenny, which the artist prepared for by using a projection machine to create a silhouette. Row mailed the silhouette to Jenny on 30 March 1780, and this rare image remains enclosed in the letter to this day. Seen here, it is a fascinating look at this man who zealously sought to balance love for a lady and a career.

Or, at least, it might be John Row. Row’s own comments about the silhouette cast interesting doubts on the likeness:

My Dear Jenny,

Inclosed I send you my shade in profile but which from my opinion of it is either badly taken, or else I make a very bad one which the person who took it tells me is the case of every one who has not high features…I appear the most stupid insipid looking fellow imaginable, and to compleat my mortification every one tells me that it is a most striking likeness.

In a subsequent letter Row went so far as to suppose that the artist had accidentally given him the silhouette of another officer. Jenny made no comment on the silhouette, but when she received the portrait she was as unimpressed with it as she was with his decision to go overseas. She wrote:

I was somewhat disappointed with the Crayon as I do not think it a favourable likeness especially in the under part of the face, in the upper it resembles you more & place it at a considerable distance & it is certainly upon the whole like, but it is a bad resemblance coarsely done & with materials which discolour & fade very soon. I however return you my thanks for it such as it is…

It is unfortunate that Jenny was so indifferent to the portrait, for it was the last image of her suitor that would ever greet her eyes. Her fears about John Row’s safety were realized. He died in September 1780, just ten weeks after arriving in the West Indies, victim not to battle but to contagious diseases that carried off nearly half of his regiment.

*****

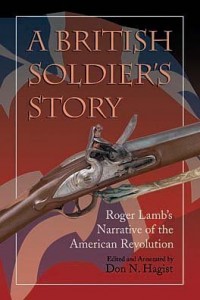

A big thanks to Don Hagist. He’ll give away an autographed copy of A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution in trade paperback format to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on my blog today or tomorrow. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Tuesday 3 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 3 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Thriller.

A big thanks to Don Hagist. He’ll give away an autographed copy of A British Soldier’s Story: Roger Lamb’s Narrative of the American Revolution in trade paperback format to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on my blog today or tomorrow. Delivery is available worldwide. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Tuesday 3 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 9 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 3 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win one of two autographed copies of my book Regulated for Murder: A Michael Stoddard American Revolution Thriller.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.