Relevant History welcomes Shannon Selin, author of Napoleon in America, alternate history which imagines what might have happened if Napoleon had escaped from St. Helena and wound up in the United States in 1821. Shannon lives in Vancouver, Canada, where she is working on the next novel in her Napoleon series. To learn more about Napoleonic and 19th century history, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr.

Relevant History welcomes Shannon Selin, author of Napoleon in America, alternate history which imagines what might have happened if Napoleon had escaped from St. Helena and wound up in the United States in 1821. Shannon lives in Vancouver, Canada, where she is working on the next novel in her Napoleon series. To learn more about Napoleonic and 19th century history, visit her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr.

*****

In writing Napoleon in America, I had to figure out what Napoleon Bonaparte might have done if he had escaped to the United States in 1821. My first task was to find out who was around at the time who might have been able to help him. To my surprise, I discovered there were many Bonapartists in America.

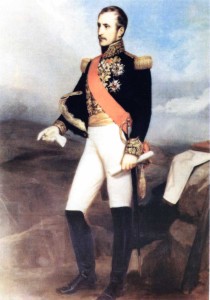

Joseph Bonaparte

Napoleon’s older brother Joseph escaped to the US in 1815, after Napoleon’s final abdication from the French throne. Trying to remain incognito, he called himself the Count of Survilliers. Joseph had amassed a fortune in Europe, where he had been King of Spain, among other things. He transferred much of it to America. He rented a house in Philadelphia and bought land in upstate New York and in Bordentown, NJ, where he built an estate called Point Breeze. It was the most impressive home in the country after the White House. According to a 19th-century account:

It had its grand hall and staircase; its great dining-rooms, art gallery and library; its pillars and marble mantels, covered with sculpture of marvelous workmanship; its statues, busts and paintings of rare merit; its heavy chandeliers, and its hangings and tapestry, fringed with gold and silver. With the large and finely carved folding-doors of the entrance, and the liveried servants and attendants, it had the air of the residence of a distinguished foreigner, unused to the simplicity of our countrymen. A fine lawn stretched on the front, and a large garden of rare flowers and plants, interspersed with fountains and chiseled animals in the rear.

Joseph remained in the United States on and off until 1839. He welcomed artists and sightseers to Point Breeze, and generously lent from his collection for art exhibitions. He has been called “one of the most significant catalysts in disseminating European culture and artistic knowledge to early nineteenth century Americans.” Though Point Breeze was demolished in the 1850s, paintings, furnishings and other items that belonged to Joseph can be found in museums and private collections across the country.

Joseph remained in the United States on and off until 1839. He welcomed artists and sightseers to Point Breeze, and generously lent from his collection for art exhibitions. He has been called “one of the most significant catalysts in disseminating European culture and artistic knowledge to early nineteenth century Americans.” Though Point Breeze was demolished in the 1850s, paintings, furnishings and other items that belonged to Joseph can be found in museums and private collections across the country.

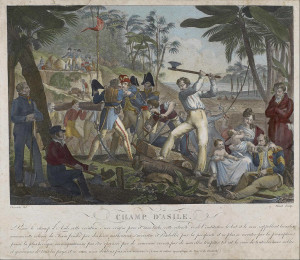

The Texas Invaders

Joseph’s home became a gathering place for other Napoleonic exiles, including officers who were avoiding death sentences in France. In 1818, two of these men—Generals Charles Lallemand and Antoine Rigaud—led some 150 Bonapartists, including four women and four children, into the wilds of Texas, which was then part of Spanish-ruled Mexico. They built a military fort called the Champ d’Asile (Field of Asylum) on the banks of the Trinity River, near the present site of Moss Bluff, TX. Within months the colony collapsed under the pressures of infighting, lack of food, Indian attacks and news of Spanish troops on the way from San Antonio to eject them. The settlers retreated to Galveston, where pirate Jean Laffite helped them return to New Orleans. A survivor recounted “how many tears our story caused to flow, we who looked as if we had returned from another world.”

Joseph’s home became a gathering place for other Napoleonic exiles, including officers who were avoiding death sentences in France. In 1818, two of these men—Generals Charles Lallemand and Antoine Rigaud—led some 150 Bonapartists, including four women and four children, into the wilds of Texas, which was then part of Spanish-ruled Mexico. They built a military fort called the Champ d’Asile (Field of Asylum) on the banks of the Trinity River, near the present site of Moss Bluff, TX. Within months the colony collapsed under the pressures of infighting, lack of food, Indian attacks and news of Spanish troops on the way from San Antonio to eject them. The settlers retreated to Galveston, where pirate Jean Laffite helped them return to New Orleans. A survivor recounted “how many tears our story caused to flow, we who looked as if we had returned from another world.”

Though the Champ d’Asile was short-lived, it spurred the United States and Spain to agree on the disputed border between their territories. The Transcontinental Treaty of 1819, also known as the Adams-Onís Treaty, transferred Florida to the United States, established the Sabine River as the boundary between Louisiana and Texas, and defined the Mexican border all the way to the west coast.

The Army Man

Not all of Napoleon’s officers engaged in unsavory pursuits. General Simon Bernard, a French military engineer, was issued a special commission in the US Army. James Monroe (then Secretary of State) wrote to General Andrew Jackson in 1816: “It required much delicacy in the arrangement, to take advantage of [Bernard’s] knowledge and experience in a manner acceptable to himself, without wounding the feelings of the officers of our own corps…I…find him a modest unassuming man, who preferred our country…to any in Europe, in some of which he was offered employment, and in any of which he may probably have found it.”

Not all of Napoleon’s officers engaged in unsavory pursuits. General Simon Bernard, a French military engineer, was issued a special commission in the US Army. James Monroe (then Secretary of State) wrote to General Andrew Jackson in 1816: “It required much delicacy in the arrangement, to take advantage of [Bernard’s] knowledge and experience in a manner acceptable to himself, without wounding the feelings of the officers of our own corps…I…find him a modest unassuming man, who preferred our country…to any in Europe, in some of which he was offered employment, and in any of which he may probably have found it.”

Bernard is best known for designing Fort Monroe in Virginia, the largest stone fort in America. He also designed Forts Adams, Hamilton, Macon and Morgan. He returned to France in 1831, after the Bourbons were overthrown, and later served as France’s Minister of War. When Bernard died in Paris in 1839, President Martin Van Buren directed all US Army officers to wear mourning dress for thirty days.

Other Bonapartists of Note

General Henri Lallemand (brother of Charles) settled in Philadelphia and wrote a two-volume Treatise on Artillery, which the US Army adopted as its standard manual. General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes joined the Society for the Cultivation of the Vine and Olive, which successfully petitioned Congress to grant the French emigrants land on the Tombigbee River in Alabama. His property at Demopolis included a log cabin, in the centre of which stood a bronze bust of Napoleon, surrounded by swords, pistols and flag-draped walls.

Pierre-François Réal, who served in key police positions throughout Napoleon’s reign, settled at Cape Vincent, NY. He built an octagon-shaped dwelling, known as the “cup and saucer house,” and devoted one of the rooms to Napoleonic memorabilia. A number of exiled Bonapartists wound up in the area. In honour of its French heritage, Cape Vincent hosts an annual French Festival, complete with a Napoleon-led parade.

Other Napoleonic soldiers had to scrape a living in occupations to which they were unaccustomed, such as farming, teaching and shopkeeping. Many did not thrive. Captain Louis Lauret wrote: “I have become a man of the woods, wandering in the forests of Georgia….I am on my way to Florida, where I plan to camp out this winter.” This allowed Lauret to “avoid the sight of the world, which fills me with horror.” Though they tended to return to France as soon as it was safe to do so, the Bonapartists had a lasting impact on American place names, culture, and mutual Franco-American sympathy among their descendants.

Read more about the characters mentioned above, and other Bonapartists who went to America, on my blog.

*****

A big thanks to Shannon Selin. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Napoleon in America to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. A winner within the US or Canada may choose between an ebook or a paperback copy.

A big thanks to Shannon Selin. She’ll give away an ebook copy of Napoleon in America to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. A winner within the US or Canada may choose between an ebook or a paperback copy.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.