Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native and award-winning author Jeri Westerson, who writes the critically acclaimed Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mysteries, historical novels, paranormal novels, and LGBT mysteries. To-date, her medieval mysteries have garnered twelve industry award nominations, from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri is the former president of the SoCal chapter of Mystery Writers of America, former vice president of Sisters in Crime Los Angeles, and frequently guest lectures on medieval history at local colleges and museums. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes back Los Angeles native and award-winning author Jeri Westerson, who writes the critically acclaimed Crispin Guest Medieval Noir Mysteries, historical novels, paranormal novels, and LGBT mysteries. To-date, her medieval mysteries have garnered twelve industry award nominations, from the Agatha to the Shamus. Jeri is the former president of the SoCal chapter of Mystery Writers of America, former vice president of Sisters in Crime Los Angeles, and frequently guest lectures on medieval history at local colleges and museums. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

The image is this: Pitchfork and torch wielding peasants; unbridled thievery on the streets; outlaws stalking the woods. Is this your idea of crime in the Middle Ages? For many it is. But how accurate is this?

Writing my medieval mysteries requires researching crime and punishment in that time period. It’s a thick field to winnow. But we are fortunate indeed that many court records of the period survive. The English loved their jurisprudence. In fact, many of the law terms we use today come down to us from medieval times. And it was never a simple case of “off with his head” or throw him in jail for a spot of torture. The law was as formal then as it is now. And terms were spelled out.

Spelling out murder

In the twelfth century, two kinds of murder were identified: Murdrum was a slaying done in secret, where the victim is taken unaware and could not retaliate. The other was simplex homicidium or simple homicide, a killing that was not planned or one that was accidental.

The term was stretched further to a third category: slaying in hot blood—a duel, or protecting the honor of one’s marriage—as “manslaughter.”

It is interesting to note that of the two hundred cases of homicide brought to the infamous Newgate prison in the period 1281-90, a verdict of guilty was returned only 21 percent of the time. Did this mean that the perpetrators were not guilty as charged? In some instances, bribery might get you out of hot water, and, of course, the higher up in rank you were, the better your chances of getting off. That is not to say that being a nobleman was a get-out-of-gaol-free card. Not always. If the crime was particularly heinous you might not be found innocent or even obtain a pardon by the king.

As far as juries were concerned, there seemed to be some argument about getting petty jurors from the neighborhood of the accused or getting them from farther afield. But when it seemed that more convictions were to be had from local jurors who might have known the accused, then that became the preference, truly a jury of your peers.

In the late fourteenth century, juries consisted of petty jurors, twenty-four knights or “other proven and law-worthy men who were not related to the subjects.” Many petty jurors were poor men, serving for payment and essentially shanghaied into the affair by the sheriffs.

There would be no Perry Mason moments at the trial. Witnesses rarely spoke at the trial itself, having given their testimony earlier to the Coroner or his clerks. The accused could challenge certain jurors, charging that they did not want them to sit on their jury.

And what did lawyers do? You had no right to an attorney then, but if you could afford one, he could certainly instruct you on how to argue your innocence, for it was up to you to speak up. Silence was construed as guilt.

The peasants are revolting

What you did have was a set of rules and procedures. Certainly there was lawlessness, but there was a citizen’s love of order as well. Were the peasants revolting (no jokes, please)? On occasion, and famously so. Wat Tyler rebelled against the low wages and high taxes imposed on the working man in 1381. It was one of King Richard II’s early challenges in his reign, and he met with Tyler in an open field to discuss the terms. Tyler was subsequently ambushed and the rebellion was brought down, and one is free to speculate whether Richard dealt unfairly with him or was wily as any king should be.

What about those scary woods? It certainly wasn’t wise to travel alone outside the city walls. If you went on a pilgrimage or to a market town, you generally traveled with a group, because it was true that outlaws menaced the forests, and travelers could fall prey to them.

But were cities and villages more lawless than we are now? I would argue against that prognosis. Even with the ultimate punishment of death for many petty crimes, crime did not cease to exist. People were as desperate then as they are now. My novels are set about forty years after the Black Death swept over Europe and took a third of the population. Many depravations followed. Imagine a third of the workforce suddenly missing. A third of farmers; a third of sheepherders and wool traders; a third of craftsmen and other tradesmen; a third of fishermen and apprentices. It took a long time for economic recovery and in the meantime, burglary, robbery, and murder increased. But after a time of economic recovery, these crimes did decrease.

When events happened so long ago, it is human nature to attribute a certain level of uncivilized behavior as compared with those in modern times. But though we might have a difficult time understanding the mores and culture of a bygone era, human nature and the same petty grievances haven’t changed all that much. Which is why a medieval mystery, while set long ago, can resonate with readers today.

For further reading (and I warn you, most of it is pretty dry), try the following:

o The Criminal Trial in Later Medieval England, J. G. Bellamy

o Public Order and Law Enforcement: The Local Administration of Criminal Justice, 1294-1350, Anthony Musson

o Crime and Conflict in English Communities, 1300-1348, Barbara A. Hanawalt

o Crime and Public Order in England in the Later Middle Ages, John Bellamy

o Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury, 1200-1800, Thomas Andrew Green

*****

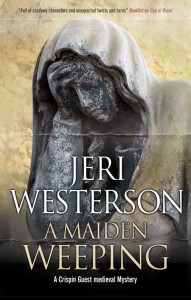

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away an ebook of A Maiden Weeping to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Jeri Westerson. She’ll give away an ebook of A Maiden Weeping to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.