Relevant History welcomes back Donis Casey, author of ten Alafair Tucker Mysteries from Poisoned Pen Press. Her award-winning historical mystery series, featuring the sleuthing mother of ten children who will do anything, legal or not, for her kids, is set in Oklahoma during the booming 1910s. While researching her own genealogy, Donis discovered so many ripping tales of murder, dastardly deeds, and general mayhem that she said to herself, “Donis, you should write a series.” Donis is a former teacher, academic librarian, and entrepreneur who lives in Tempe, AZ. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes back Donis Casey, author of ten Alafair Tucker Mysteries from Poisoned Pen Press. Her award-winning historical mystery series, featuring the sleuthing mother of ten children who will do anything, legal or not, for her kids, is set in Oklahoma during the booming 1910s. While researching her own genealogy, Donis discovered so many ripping tales of murder, dastardly deeds, and general mayhem that she said to herself, “Donis, you should write a series.” Donis is a former teacher, academic librarian, and entrepreneur who lives in Tempe, AZ. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook and Goodreads.

*****

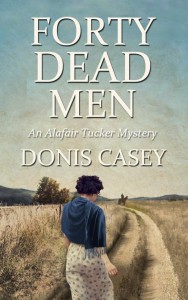

The Alafair Tucker Mystery series started in 1912 with The Old Buzzard Had It Coming and has moved forward years or months with each book. The tenth book in the series, Forty Dead Men, takes place early in 1919, shortly after the end of World War I and at the end of the Great Influenza epidemic.

My grandparents were all in their early twenties during WWI, but none of them ever told me anything about their lives while the war was on. Neither of my grandfathers went. I fear I grew up thinking that the distant European war didn’t have much of an effect on folks buried deep in the hills of Arkansas and Oklahoma.

Was I ever wrong.

History books and articles are good for giving a writer an overview of a time period, but what I am really interested in writing about is what the people who lived through an event thought about it at the time. One great thing about writing historical fiction is that when you do your research, you discover that what really happened is often more amazing than anything you could make up.

I am particularly proud of Forty Dead Men, which deals with the psychological effects of warfare on a veteran of the First World War. They called it “shell shock” back then. Now we call it post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Surviving the horrors of war

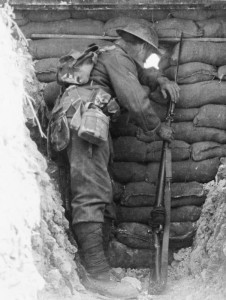

Soldiers have been psychologically affected by the horrors of war since the beginning of human history, and every society has dealt with it in different ways. But the modern technological advances in weaponry during WWI brought the problem to a whole new level. Imagine being trapped for weeks on end in a wet, stinking, muddy trench being bombarded day and night, hour after hour, nowhere to go, completely at the mercy of fate. If a shell fell on your position, you were toast, and there was nothing you could do to protect yourself. Then again, at regular intervals, some officer behind the lines would order you and your mates to go over the top and get mowed down by machine gun fire, and if, like a sane person, you didn’t do it, you were liable to be shot by your own officers.

Soldiers have been psychologically affected by the horrors of war since the beginning of human history, and every society has dealt with it in different ways. But the modern technological advances in weaponry during WWI brought the problem to a whole new level. Imagine being trapped for weeks on end in a wet, stinking, muddy trench being bombarded day and night, hour after hour, nowhere to go, completely at the mercy of fate. If a shell fell on your position, you were toast, and there was nothing you could do to protect yourself. Then again, at regular intervals, some officer behind the lines would order you and your mates to go over the top and get mowed down by machine gun fire, and if, like a sane person, you didn’t do it, you were liable to be shot by your own officers.

Shell shock became a real problem. Before the U.S. entered the war, British doctors thought shell shock was a physical thing caused by exposure to exploding shells. But it didn’t take long before that notion was proved wrong. “Shell shock” happened to men who had never come under fire. The symptoms of shell shock were extraordinarily varied. Hysteria, paralysis, blindness, deafness, loss of the ability to speak or control one’s limbs were the most common among enlisted soldiers. Officers had fewer physical and more psychological symptoms like nightmares, insomnia, depression and disorientation. Still, four times as many officers suffered breakdowns than regular soldiers. That was because they tended to repress their emotions in order to set an example for their men. Sometimes officers were so ashamed of their fear that they flung themselves into impossibly dangerous positions just to keep face before their men.

Living with shell shock

There really wasn’t much help for these wounded soldiers. Some doctors tried electric shock therapy, hypnosis, solitary confinement, even shaming. According to the U.S. Veterans’ Administration, soldiers often received only a few days’ rest before returning to the war zone. I saw a comment online that was written by a grandson of a British WWI vet, who wrote that his grandfather recovered from his physical wounds and became a productive member of society. But he “medicated his emotional wounds with alcohol and extra-martial affairs. Even in his advanced age, he could not be in the kitchen when the kettle was whistling.”

My fictional veteran, Alafair’s eldest son, Gee Dub Tucker, was an officer with a front line unit who suffered a head wound during a bombardment, but was loaned to a British unit only a few days after his concussion. He was assigned to act as a sharpshooter. Nowadays we call them snipers.

What Gee Dub witnessed, and even more so, what he did while he was in France, haunts him after his return to the family farm in Oklahoma. He seems normal to his family. Except for his mother, who sees that something is terribly wrong with him. The restless veteran has taken to roaming the quiet hills around his family farm. One rainy day while out riding he spies a woman trudging along the country road. Holly Johnson reveals she’s forged her way from Maine to Oklahoma in hopes of finding the soldier she married before he shipped to France. At the war’s end, he disappeared without a trace. Gee Dub is glad to have a project and tries to help Holly, but ends up the prime suspect when Holly’s husband turns up dead. Alafair will not let that stand. As one reviewer noted, “she’ll do anything to protect her kin…No one can resist her—at least, not for long.”

*****

A big thanks to Donis Casey. She’ll give away a signed, hardbound copy of Forty Dead Men to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. and Canada only.

A big thanks to Donis Casey. She’ll give away a signed, hardbound copy of Forty Dead Men to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. and Canada only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.