Relevant History welcomes Matthew Harffy, who lived in Northumberland as a child. The area had a great impact on him. Decades later, a documentary about Northumbria’s Golden Age sowed the kernel of an idea for a series of novels. The first is the action-packed tale of vengeance and coming of age, The Serpent Sword. Matthew has worked in the IT industry and as an English teacher and translator in Spain. He has co-authored seven published academic articles, ranging in topic from the ecological impact of mining to the construction of a marble pipe organ. He lives in England with his wife and two daughters. To learn more about Matthew’s books, check out his web site, and follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes Matthew Harffy, who lived in Northumberland as a child. The area had a great impact on him. Decades later, a documentary about Northumbria’s Golden Age sowed the kernel of an idea for a series of novels. The first is the action-packed tale of vengeance and coming of age, The Serpent Sword. Matthew has worked in the IT industry and as an English teacher and translator in Spain. He has co-authored seven published academic articles, ranging in topic from the ecological impact of mining to the construction of a marble pipe organ. He lives in England with his wife and two daughters. To learn more about Matthew’s books, check out his web site, and follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

I sat down this evening with my family to eat one of our favourite meals—Chilli con Carne. Beef in a rich sauce of tomato, onions, kidney beans, peppers, cumin, chilli pepper powder, cinnamon, garlic, cocoa, salt, oregano and black pepper. All of this on a bed of basmati rice. It was delicious!

I sat down this evening with my family to eat one of our favourite meals—Chilli con Carne. Beef in a rich sauce of tomato, onions, kidney beans, peppers, cumin, chilli pepper powder, cinnamon, garlic, cocoa, salt, oregano and black pepper. All of this on a bed of basmati rice. It was delicious!

I got thinking about how many of the things I was eating and enjoying would not have been available to the characters in my book, The Serpent Sword. It is set in Britain in 633 A.D., and whilst much of the story is concerned with epic battles, warriors and kings, the fate of nations, and the search for justice in a dark and troubled time, everyone needs to eat!

Dark Ages grub

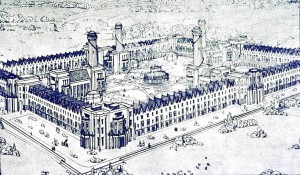

Food in what is commonly known as the “Dark Ages” was a far cry from our modern diet. Now we can easily obtain fruit, vegetables and spices imported from all over the world. But Europeans had not yet been to the New World (or if they had, they hadn’t returned with all of the wonders of later centuries, such as tomatoes, cocoa, potatoes and the many other delicacies that came from the Americas), and whilst there were some imports from mainland Europe, Asia and Africa, these things would have been extremely rare and expensive, and of course, only items that could remain fresh for a long time, such as spices, could be imported.

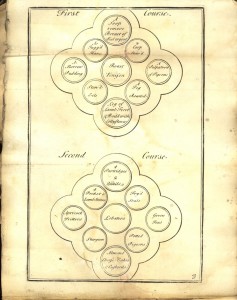

Everyday food would have been much simpler than what we are used to. Pottage would have been a staple—basically whatever was available cooked in a cauldron over the house’s central hearth. This would be accompanied by bread, baked in a clay oven or on a griddle. The vegetables used would be seasonal, so the pottage would change as the year went on. There would be times when there was some meat in the stew, such as when calves and lambs were killed in spring to leave cows and ewes with milk. At other times, there would be no meat. Hunting would be an extra source of food that would be very welcome.

Everyday food would have been much simpler than what we are used to. Pottage would have been a staple—basically whatever was available cooked in a cauldron over the house’s central hearth. This would be accompanied by bread, baked in a clay oven or on a griddle. The vegetables used would be seasonal, so the pottage would change as the year went on. There would be times when there was some meat in the stew, such as when calves and lambs were killed in spring to leave cows and ewes with milk. At other times, there would be no meat. Hunting would be an extra source of food that would be very welcome.

In general, meat would have been consumed quite sparingly. Nobles would have eaten more meat than the poor. The richer one was, the more meat one could afford. Fish was eaten fresh or, if it was to be stored for longer periods, it could be smoked or salted. Butter and cheese were made from the milk of goats, sheep and cows. Milk wouldn’t keep for long with no refrigeration, even in the British climate, so converting it to cheese and butter made it last much longer.

There was no sugar for sweets or cakes. The only sweetener was honey. Honey cakes were popular but would have been eaten a lot less frequently than we tend to eat sweet things.

Vegetables and fruit

The staple grain crops were wheat, rye, oats and barley. Wheat and rye were used to make bread, and barley was used to brew ale. Oats were eaten as porridge and also fed to animals.

Commonly eaten vegetables were carrots, but not the orange things we know. These would have been purple-red and much smaller. The inhabitants of the British Isles also ate parsnips and cabbages (though these too, were wild, smaller and tougher). Peas, beans, onions and leeks were common cultivated crops too. Foraged plants, such as wild garlic and burdock, would also have been added to the menu.

Commonly eaten vegetables were carrots, but not the orange things we know. These would have been purple-red and much smaller. The inhabitants of the British Isles also ate parsnips and cabbages (though these too, were wild, smaller and tougher). Peas, beans, onions and leeks were common cultivated crops too. Foraged plants, such as wild garlic and burdock, would also have been added to the menu.

Although the food would not have been as rich and spicy as my chilli, there were some herbs that could be used to add flavour to dishes. These included coriander, dill and thyme. The wealthy could possibly obtain imported spices such as ginger, cinnamon, cloves, mace and pepper. However, it is unlikely many would have tasted such things. The import of these goods would become more widespread in later centuries as trade routes to the east were opened up.

Anglo-Saxons ate quite a lot of fruit. Apples, plums, cherries and sloes were all consumed. Of course, no oranges, lemons or bananas!

Drinks

The most popular drink was ale. This would not have been the ale we drink (and I love!) today. Instead it would have been a less alcoholic drink, flavoured with gruit (basically, whatever flowers or herbs you had to hand). Brewed with barley, it would not have had hops, which are what give modern beers their crisp dryness.

The most popular drink was ale. This would not have been the ale we drink (and I love!) today. Instead it would have been a less alcoholic drink, flavoured with gruit (basically, whatever flowers or herbs you had to hand). Brewed with barley, it would not have had hops, which are what give modern beers their crisp dryness.

The drink that perhaps epitomises the images we have of this period, is mead. Beowulf and other heroic Old English poetry talk of the medubenc (mead bench) in the lord’s hall, where warriors would drink from great horns (literally the hollow horns of cattle). Mead was made from honey and often flavoured with herbs, or meduwyrt (mead plant).

Wine was imported and therefore rare and expensive. Cider (or apple-wine) was drunk, as were fruit juices.

The process for distilling spirits was not yet known, so there was no whisky, brandy or the like.

So food and drink were less varied than today and a far cry from our modern diet, high in fats, sugars and protein. Today we are spoiled, seldom eating something we do not like the flavour of. The amount of fibre and vegetables in the diet of the Dark Ages, coupled with the effort required to pull together enough to survive, would today be seen as the basis for a healthy lifestyle.

However, it was not all good news. In the worst times, when crops failed or when the winter stores were depleted, no amount of effort was enough to keep sufficient food on the table. Death from starvation was not uncommon in this period, and there is even evidence of cannibalism!

I’m happy to stick with my chilli con carne and all the trimmings, but there are many people today who extol the virtues of living in closer connection with the seasons, eating only locally-sourced produce. Perhaps we should call this modern trend to lower our carbon footprint “the Dark Ages Diet.”

References:

http://regia.org/research/life/food.htm

Images attributions:

“Bowl of chili” by Carstor – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bowl_of_chili.jpg#/media/File:Bowl_of_chili.jpg

“Ecologically grown vegetables” by Elina Mark – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ecologically_grown_vegetables.jpg#/media/File:Ecologically_grown_vegetables.jpg

“Magenbitter und Halbbitter” by ChasseurBln – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magenbitter_und_Halbbitter.jpg#/media/File:Magenbitter_und_Halbbitter.jpg

“Grilled Lamb Loin Chops-01” by Naotake Murayama from Los Altos, CA, USA – Grilled Lamb Loin ChopsUploaded by Caspian blue. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grilled_Lamb_Loin_Chops-01.jpg#/media/File:Grilled_Lamb_Loin_Chops-01.jpg

*****

A big thanks to Matthew Harffy. He’ll give away a signed paperback copy of The Serpent Sword to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Matthew Harffy. He’ll give away a signed paperback copy of The Serpent Sword to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.