Relevant History welcomes Regina Jeffers, an award-winning author of cozy mysteries, Austenesque sequels and retellings, and Regency era romances. A teacher for thirty-nine years, she often serves as a consultant for Language Arts and Media Literacy programs. With multiple degrees, Regina has been a Time Warner Star Teacher, Columbus (OH) Teacher of the Year, and a Martha Holden Jennings Scholar. With five new releases coming out in 2015, she is considered one of publishing’s most prolific authors. Her novels include Darcy’s Passions, Captain Frederick Wentworth’s Persuasion, The Mysterious Death of Mr. Darcy, and The First Wives’ Club. To learn more about Regina’s books, check out her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes Regina Jeffers, an award-winning author of cozy mysteries, Austenesque sequels and retellings, and Regency era romances. A teacher for thirty-nine years, she often serves as a consultant for Language Arts and Media Literacy programs. With multiple degrees, Regina has been a Time Warner Star Teacher, Columbus (OH) Teacher of the Year, and a Martha Holden Jennings Scholar. With five new releases coming out in 2015, she is considered one of publishing’s most prolific authors. Her novels include Darcy’s Passions, Captain Frederick Wentworth’s Persuasion, The Mysterious Death of Mr. Darcy, and The First Wives’ Club. To learn more about Regina’s books, check out her web site and blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

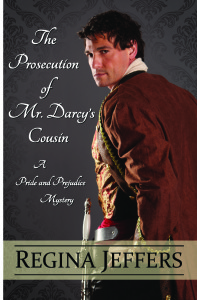

One of my upcoming releases (The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin) uses Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as part of the plot line, but as my book is set in the Regency period (1811-1820) in England, when no such distinction was made for the disease, it was important to treat the disorder’s presence in the main character’s life with a large dose of research. There are references to what we now term “PTSD” in the Bible (story of Job comes to mind), the writings of the Greek historian Herotodus (i.e., his description of the Spartan leader Leonidas—the guy from “300”), the Mahabharata, Homer’s description of Ajax’s madness, and Shakespeare’s descriptions (via Lady Percy) of Harry Percy’s nightmares and delusions, as well as the accounts of Macbeth. Samuel Pepys’s diary holds references to the trauma many experienced after the Great Fire of London. Charles Dickens wrote of the “weakness” he experienced after a train wreck that killed ten people and injured nearly fifty.

One of my upcoming releases (The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin) uses Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as part of the plot line, but as my book is set in the Regency period (1811-1820) in England, when no such distinction was made for the disease, it was important to treat the disorder’s presence in the main character’s life with a large dose of research. There are references to what we now term “PTSD” in the Bible (story of Job comes to mind), the writings of the Greek historian Herotodus (i.e., his description of the Spartan leader Leonidas—the guy from “300”), the Mahabharata, Homer’s description of Ajax’s madness, and Shakespeare’s descriptions (via Lady Percy) of Harry Percy’s nightmares and delusions, as well as the accounts of Macbeth. Samuel Pepys’s diary holds references to the trauma many experienced after the Great Fire of London. Charles Dickens wrote of the “weakness” he experienced after a train wreck that killed ten people and injured nearly fifty.

Over the years, PTSD was known as nostalgia, homesickness, ester root, neurasthenia, hysteria, compensation sickness, railway spine, shell shock, combat exhaustion, soldier’s heart, irritable heart, stress response syndrome, etc. In my story, I use the word “melancholia” for research into the disorder did not occur until well after the Regency period. Needless to say, the many wars of the late 1700s and early 1800s (American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Napoleonic Wars) in England brought this issue to a head. (For more on the many terms used for PTSD, see “From Irritable Heart to ‘Shellshock’: How Post-Traumatic Stress Became a Disease,” by Charlie Jane Anders, 4 April 2012.)

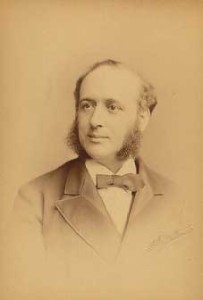

During the American Civil War, the study of “soldier’s heart” fell into the lap of Jacob Mendez Da Costa, who took up the study of the condition and advanced what we now know of the disease. Da Costa was a well-trained and observant clinician. He held the reputation of an excellent clinical teacher and served as Chairman of Medicine at the Jefferson Medical College (now Thomas Jefferson University) for nineteen years, as well as president of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1884 and again in 1895; Da Costa was one of the original members of the Association of American Physicians and its president in 1897.

During the American Civil War, the study of “soldier’s heart” fell into the lap of Jacob Mendez Da Costa, who took up the study of the condition and advanced what we now know of the disease. Da Costa was a well-trained and observant clinician. He held the reputation of an excellent clinical teacher and served as Chairman of Medicine at the Jefferson Medical College (now Thomas Jefferson University) for nineteen years, as well as president of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1884 and again in 1895; Da Costa was one of the original members of the Association of American Physicians and its president in 1897.

In the years of the Civil War, Da Costa served as assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army and at Turner’s Lane Hospital, Philadelphia. As such, he studied a type of cardiac malady (neurocirculatory asthenia) plaguing soldiers. He described the disorder in his 1871 paper “On Irritable Heart: A Clinical Study of a Form of Functional Cardiac Disorder and Its Consequences,” a landmark study in clinical medicine. The malady was soon to be known as Da Costa’s syndrome—an anxiety disorder combining effort fatigue, left-sided chest pains, breathlessness, dyspnea, a sighing respiration, palpitations, and sweating.

In the mid-20th Century, the syndrome was thought to be a form of neurosis. It is now classified as a “somatoform autonomic dysfunction.” Earl de Grey presented four reports on British soldiers with these symptoms between 1864 and 1868. He attributed the symptoms to the heavy equipment being carried by the soldiers in knapsacks strapped to their chests. Earl de Grey asserted that the constriction of the knapsack affected the heart’s ability to function. Henry Harthorme described the Civil War soldiers who suffered with similar symptoms as being exhausted and poorly nourished. The soldier’s heart complaints were assigned as lack of sleep and bad food. In 1870, Arthur Bowen Myers of the Coldstream Guards (the Foot Guards regiments of the British Army) regarded the accouterments as the source of neurocirculatory asthenia and cardiovascular neurosis.

“J. M. Da Costa’s study of 300 soldiers reported similar findings in 1871 and added that the condition often developed and persisted after a bout of fever or diarrhea. He also noted that the pulse was always greatly and rapidly influenced by position, such as stooping or reclining. A typical case involved a man who was on active duty for several months or more and contracted an annoying bout of diarrhea or fever, and then, after a short stay in the hospital, returned to active service. The soldier soon found that he could not keep up with his comrades in the exertions of a soldier’s life as he would become out of breath, and would get dizzy, and have palpitations and pains in his chest, yet upon examination some time later he appeared generally healthy. In 1876 surgeon Arthur Davy attributed the symptoms to military drill where ‘over-expanding the chest, caused dilatation of the heart, and so induced irritability.’”

*****

.

.

.

.

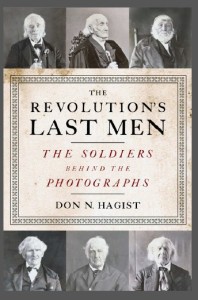

A big thanks to Regina Jeffers. She’ll give away one of the four ebooks pictured above to four people: Darcy’s Passions: Pride and Prejudice Retold Through His Eyes, Captain Frederick Wentworth’s Persuasion: Austen’s Classic Retold Through His Eyes, Elizabeth Bennet’s Deception: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary, and Mr. Darcy’s Fault: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary Novella. I’ll choose the winners from among those who contribute a comment on my blog this week by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.