Historical fantasy author Judith Starkston describes a day in the life of Puduhepa, Queen of the Hittites.

~~~

Relevant History welcomes back Judith Starkston, author of the award-winning historical fantasy Priestess of Ishana and the Trojan War novel Hand of Fire. She has degrees in Classics from the University of California, Santa Cruz and Cornell. Priestess of Ishana combines history with magical elements found in Hittite rites, and in the series, Queen Puduhepa is renamed Tesha after the Hittite word for “dream.” (Read the post to find out why.) To learn more about Judith and her books, visit her web site, follow her on Facebook and Twitter—and sign up for her newsletter to receive a free Bronze Age short story and cookbook.

Relevant History welcomes back Judith Starkston, author of the award-winning historical fantasy Priestess of Ishana and the Trojan War novel Hand of Fire. She has degrees in Classics from the University of California, Santa Cruz and Cornell. Priestess of Ishana combines history with magical elements found in Hittite rites, and in the series, Queen Puduhepa is renamed Tesha after the Hittite word for “dream.” (Read the post to find out why.) To learn more about Judith and her books, visit her web site, follow her on Facebook and Twitter—and sign up for her newsletter to receive a free Bronze Age short story and cookbook.

*****

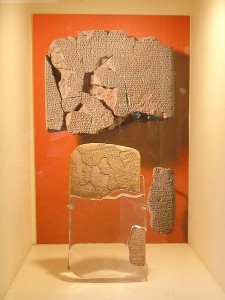

Queen Puduhepa pressed her seal into the first extant peace treaty in history. The Treaty of Kadesh was between her kingdom of the Hittites (in what is now Turkey) and Rameses II, Pharaoh of Egypt, during the Late Bronze Age, in the thirteenth century BCE. In the twentieth century, her letters, treaties, religious codifications and judicial decrees came to light when archaeologists dug up the great cuneiform libraries of her capital, Hattusha.

Queen Puduhepa pressed her seal into the first extant peace treaty in history. The Treaty of Kadesh was between her kingdom of the Hittites (in what is now Turkey) and Rameses II, Pharaoh of Egypt, during the Late Bronze Age, in the thirteenth century BCE. In the twentieth century, her letters, treaties, religious codifications and judicial decrees came to light when archaeologists dug up the great cuneiform libraries of her capital, Hattusha.

She reigned for some seventy years. At about fifteen she married Hattusili, who later became the Great King of the Hittites and she the queen. In the years following her reign, unknown forces destroyed and buried the Hittite Empire, and this remarkable queen was forgotten to history. From clay tablets, now deciphered and translated, we can reconstruct some of the typical events from a day in the life of Puduhepa.

Even the water matters

As Puduhepa’s hypothetical day begins, she reaches for that first cup of water to quench her morning thirst. From one of the tablets, we have instructions to palace personnel about the royal water:

All the kitchen personnel—the cupbearer, the table-man, the cook, the baker, the dairy man (the list goes on) you will have to swear an oath… Fill a bitumen cup with water and pour it out toward the Sun-god and speak as follows: “Whoever does something in an unclean way and offers to the king (or queen) polluted water, pour you, O gods, that man’s soul out like water!”

and

You who are water carriers, be very careful with water! Strain the water with a strainer! At some time I, the king, found a hair in the water pitcher in Sanahuitta. I expressed my anger to the water carriers “This is scandalous. … If he is found guilty, he shall be killed!”

According to the Hittites, a hair could be used to place a curse on the king or queen. Just slip the correct hair in with the proper incantations, and you could shorten the king’s life, cause him a wasting illness, or any number of other mysterious problems. Curses were a regular concern—which explains the stiff penalty in this case, although ritual purity in general for the royal family was a tremendous concern for reasons of proper relationship and harmony with the gods rather than notions of healthfulness.

Setting things right with the gods

Once Puduhepa refreshes herself with water free from any curses, she might prepare herself to go to the temple to make offerings and pray. Puduhepa’s love and devotion for her husband were legendary. They met accidentally—except they both attributed it to their patron goddess Ishtar—and it was love at first sight. In a dream, Ishtar commanded Hattusili to marry Puduhepa. Puduhepa also had dreams from Ishtar regularly, and these two mystics, who led extremely pragmatic lives, found great solace in each other. When Hattusili was ill, as he often was both with a mysterious eye ailment and something painful in his feet, Puduhepa prayed fervently for his health.

In the inner sanctum of the temple where only the royal family and the priests were allowed access, Pudhepa makes offerings to the divine statues of the gods. Each day priests and priestess provided food and drink for and bathed and dressed their gods. In this brightly frescoed space, before gold and silver statues draped in finery, Puduhepa offers a goat or bull for sacrifice. She has selected bread offerings from a myriad of shapes—today perhaps a hand or bird—and her breads are sweetened with honey and soaked in olive oil.

To ensure her husband’s health, she beseeches the gods to bring Hattusili long life and well-being. In one of her extant prayers, she opens by reminding the Sun-goddess Arinna that Hattusili had recaptured the goddess’s sacred city of Nerik, and the traditional offerings to her are once again being made there. After this reminder of the goddess’s debt to Hattusili, Puduhepa goes on to make this plea:

Since I, Puduhepa, am a woman of the birthstool (a midwife or possibly a mother of many children), … have pity on me, O Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, and grant me what I ask of you! Grant life to Hattusili, your servant! Through the Fate-goddesses and the Mother-goddesses may long years, days and strength be granted to him.

Later in the same prayer, now directed to one of Arinna’s attending goddesses, Puduhepa suggests that maybe someone has made an offering to the gods to damage Hattusili or has otherwise cursed him, and that this goddess should undo that harm. In return Puduhepa will give her a life-sized silver statue of Hattusili with golden head, hands and feet. That’s a lot of wifely devotion and an interesting window into how the Hittite queen viewed her relationship with the gods. The queen wasn’t afraid to resort to divine bribery.

Counselor, priestess, judge and diplomat

Next in her day she could select from a wide range of activities we know she engaged in. She served as her husband’s primary source of counsel, as a priestess of Ishtar, as supreme court judge for the Hittite Kingdom, as an astute political negotiator, and as a marriage broker (a form of diplomacy) between great rulers such as Rameses and her husband’s many children (by concubines as well as Puduhepa’s own).

Finally some food

At the end of her busy day she had a supper of lamb roasted in cumin and garlic with a side dish of lentils and leeks. Some cucumber in yogurt cooled her tongue. Perhaps servants laid out the exotic, imported treat of dates on a silver tray for her enjoyment. More likely the finishing sweet came in the form of dried figs and apricots. She might even have drunk her beer through a straw, which as near as we can tell was a filter to keep the bits of grain out of one’s mouth.

*****

A big thanks to Judith Starkston! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Priestess of Ishana to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Judith Starkston! She’ll give away an ebook copy of Priestess of Ishana to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Relevant History welcomes Karen A. Chase, an author and photographer, and a Daughter of the American Revolution with the Commonwealth Chapter in Virginia. Her first novel, Carrying Independence, is historical fiction about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Karen will be a Virginia Foundation for the Humanities fellow for the 2019-2020 academic year, with full residency at the Library of Virginia. Originally from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, she is now chasing histories from Richmond, VA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Karen A. Chase, an author and photographer, and a Daughter of the American Revolution with the Commonwealth Chapter in Virginia. Her first novel, Carrying Independence, is historical fiction about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Karen will be a Virginia Foundation for the Humanities fellow for the 2019-2020 academic year, with full residency at the Library of Virginia. Originally from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, she is now chasing histories from Richmond, VA. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  This might have been the news report from this day, 9 July, back in 1776. Soldiers of the Continental Army had gathered in Bowling Green, New York, at the feet of a statue of King George III. It had been erected just six years earlier by a populace grateful that the King had repealed the Townsend Acts. But on this day the Declaration of Independence was read aloud. The list of grievances cited against their King was long—27 points outlining an apathetic and self-appointed despot “unfit to be a ruler of a free people.”

This might have been the news report from this day, 9 July, back in 1776. Soldiers of the Continental Army had gathered in Bowling Green, New York, at the feet of a statue of King George III. It had been erected just six years earlier by a populace grateful that the King had repealed the Townsend Acts. But on this day the Declaration of Independence was read aloud. The list of grievances cited against their King was long—27 points outlining an apathetic and self-appointed despot “unfit to be a ruler of a free people.” Currently being developed is also

Currently being developed is also  A big thanks to Karen A. Chase! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Carrying Independence to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the United States and Canada.

A big thanks to Karen A. Chase! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Carrying Independence to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the United States and Canada. Relevant History welcomes Kathleen Heady, author of three mystery novels featuring Nara Blake, a woman from a Caribbean island who moves to England. Kathleen’s work in progress takes Nara to Spain, where she learns about Felicia Browne, a British woman who died fighting Fascists in the Spanish Civil War. Kathleen lives in North Carolina with her husband and two cats. Her house looks out on Carolina woods, almost fulfilling her childhood dream of living in a tree house. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Kathleen Heady, author of three mystery novels featuring Nara Blake, a woman from a Caribbean island who moves to England. Kathleen’s work in progress takes Nara to Spain, where she learns about Felicia Browne, a British woman who died fighting Fascists in the Spanish Civil War. Kathleen lives in North Carolina with her husband and two cats. Her house looks out on Carolina woods, almost fulfilling her childhood dream of living in a tree house. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  As I began research for my current work in progress, I felt drawn to that beautiful part of the world that straddles France and Spain, and the time period leading up to World War II. I looked for a connection between Britain, Spain, and the art world. This led me to discover the story of a woman named Felicia Browne, the first British volunteer and only British woman to die in the Spanish Civil War.

As I began research for my current work in progress, I felt drawn to that beautiful part of the world that straddles France and Spain, and the time period leading up to World War II. I looked for a connection between Britain, Spain, and the art world. This led me to discover the story of a woman named Felicia Browne, the first British volunteer and only British woman to die in the Spanish Civil War. The period of the Spanish Civil War is one that is still difficult to understand. It was a tragedy for the Spanish people and many others who volunteered to help the Spanish fight for freedom from fascism. The period included the tragic bombing of Guernica,

The period of the Spanish Civil War is one that is still difficult to understand. It was a tragedy for the Spanish people and many others who volunteered to help the Spanish fight for freedom from fascism. The period included the tragic bombing of Guernica,  A big thanks to Kathleen Heady! She will give away a paperback copy of Lydia’s Story to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Kathleen Heady! She will give away a paperback copy of Lydia’s Story to two readers who contribute comments on my blog. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes Clara McKenna, who writes the new historical cozy Stella & Lyndy Mysteries series about an unlikely couple who mix love, murder, and horseracing in Edwardian England. She is a member of Sisters in Crime and the founding member of Sleuths in Time, a cooperative group of historical mystery writers who encourage and promote each other’s work. With an incurable case of wanderlust, she travels every chance she gets, England being a favorite destination. When she can’t get to England, she happily writes about it from her home in Iowa. To learn more about her and her books, vist her

Relevant History welcomes Clara McKenna, who writes the new historical cozy Stella & Lyndy Mysteries series about an unlikely couple who mix love, murder, and horseracing in Edwardian England. She is a member of Sisters in Crime and the founding member of Sleuths in Time, a cooperative group of historical mystery writers who encourage and promote each other’s work. With an incurable case of wanderlust, she travels every chance she gets, England being a favorite destination. When she can’t get to England, she happily writes about it from her home in Iowa. To learn more about her and her books, vist her  Some did so willingly; some were not given a choice. America’s richest heiress, Consuelo Vanderbilt, was a spectacular example of the latter. In love with another man, she was bullied relentlessly by her mother until she agreed to marry the Duke of Marlborough. Consuelo was thought to have been heard weeping beneath her wedding veil during the ceremony. She divorced the Duke in 1920.

Some did so willingly; some were not given a choice. America’s richest heiress, Consuelo Vanderbilt, was a spectacular example of the latter. In love with another man, she was bullied relentlessly by her mother until she agreed to marry the Duke of Marlborough. Consuelo was thought to have been heard weeping beneath her wedding veil during the ceremony. She divorced the Duke in 1920. an indelible mark. Nancy Langhorne Astor, of Virginia, became the first woman to sit as a Member of Parliament. Jennie Jerome Spencer-Churchill, of New York, is best known as Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s mother. Francis Work Burke Roche of Ohio’s great-great-grandson, Prince William, will one day sit on the throne of England. So as even as Downton Abbey, the highly acclaimed television series, was inspired by these pioneering, unforgettable American women, so should we all be.

an indelible mark. Nancy Langhorne Astor, of Virginia, became the first woman to sit as a Member of Parliament. Jennie Jerome Spencer-Churchill, of New York, is best known as Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s mother. Francis Work Burke Roche of Ohio’s great-great-grandson, Prince William, will one day sit on the throne of England. So as even as Downton Abbey, the highly acclaimed television series, was inspired by these pioneering, unforgettable American women, so should we all be. A big thanks to Clara McKenna! She will give away one hardback copy of Murder at Morrington Hall to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Clara McKenna! She will give away one hardback copy of Murder at Morrington Hall to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only. Relevant History welcomes Nancy Haines, who worked seventeen years as an engineer, then ran an antiquarian bookstore. After her retirement, she fulfilled a lifelong dream to be an author. She published a nonfiction book, We Answered with Love, about Quaker relief service in France during WWI based on the love letters of two pacifists, and a picture book about spiritual decision making for Quaker children. She is currently researching the lives of the Quakers who were the original European settlers of Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she and her husband now reside, for a nonfiction book (or possibly try her hand at a novel). To learn more about her and her books, visit her

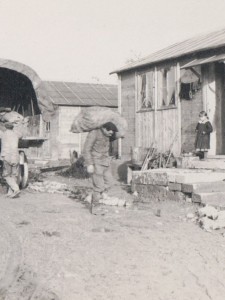

Relevant History welcomes Nancy Haines, who worked seventeen years as an engineer, then ran an antiquarian bookstore. After her retirement, she fulfilled a lifelong dream to be an author. She published a nonfiction book, We Answered with Love, about Quaker relief service in France during WWI based on the love letters of two pacifists, and a picture book about spiritual decision making for Quaker children. She is currently researching the lives of the Quakers who were the original European settlers of Hillsborough, North Carolina, where she and her husband now reside, for a nonfiction book (or possibly try her hand at a novel). To learn more about her and her books, visit her  The Quakers decided to concentrate their work in Verdun, the region that was hardest hit by the German invasion. As the Allies advanced northwest of Verdun, the Army gave Quaker workers permission to move in to meet the needs of over ten thousand refugees. The fighting had been almost continuous in this area. Only about five percent of the houses were left standing and these were badly damaged. One British worker described the abandoned battlefields:

The Quakers decided to concentrate their work in Verdun, the region that was hardest hit by the German invasion. As the Allies advanced northwest of Verdun, the Army gave Quaker workers permission to move in to meet the needs of over ten thousand refugees. The fighting had been almost continuous in this area. Only about five percent of the houses were left standing and these were badly damaged. One British worker described the abandoned battlefields: With financial assistance from the French government, the Quakers occupied the former divisional headquarters of the French and American armies. This center included barracks for the workers and barns to store supplies to support the workers, goods to be sold to the villagers, agricultural machinery, stables and breeding barns for livestock, and generators for electricity. The American Army provided trailers and fuel for distributing the supplies and building materials to the villages.

With financial assistance from the French government, the Quakers occupied the former divisional headquarters of the French and American armies. This center included barracks for the workers and barns to store supplies to support the workers, goods to be sold to the villagers, agricultural machinery, stables and breeding barns for livestock, and generators for electricity. The American Army provided trailers and fuel for distributing the supplies and building materials to the villages. A big thanks to Nancy Haines! She’ll give away one paperback copy of We Answered with Love to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Nancy Haines! She’ll give away one paperback copy of We Answered with Love to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes Kathryn McMaster, a writer, entrepreneur, wife, mother, and organic farmer. She is also a bestselling author of historical murder mysteries set in the Victorian era, and modern true crime cases based on Canadian and American murders committed by young teens and couples. She co-owns the website

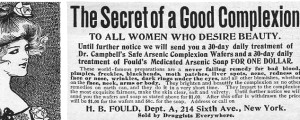

Relevant History welcomes Kathryn McMaster, a writer, entrepreneur, wife, mother, and organic farmer. She is also a bestselling author of historical murder mysteries set in the Victorian era, and modern true crime cases based on Canadian and American murders committed by young teens and couples. She co-owns the website  When I was at school learning about the Victorian Era of 1837–1901, we were taught about the social impact and impoverishment the Industrial Revolution brought to certain sectors of society when machinery replaced manual labor. What we were not taught was how prevalent arsenic was during this period in the production of household goods, fabric, and even beauty products used by those in the upper echelons of society.

When I was at school learning about the Victorian Era of 1837–1901, we were taught about the social impact and impoverishment the Industrial Revolution brought to certain sectors of society when machinery replaced manual labor. What we were not taught was how prevalent arsenic was during this period in the production of household goods, fabric, and even beauty products used by those in the upper echelons of society. During this time in history it was discovered that by giving horses arsenic in small amounts it gave them stamina which enabled them to endure long distances. People started to dabble and found that in small doses it did the same for them. Arsenic then began to appear as an ingredient in beauty wafers and soaps. Articles in popular magazines such as Blackwoods encouraged women to bathe in it to soften their skin.

During this time in history it was discovered that by giving horses arsenic in small amounts it gave them stamina which enabled them to endure long distances. People started to dabble and found that in small doses it did the same for them. Arsenic then began to appear as an ingredient in beauty wafers and soaps. Articles in popular magazines such as Blackwoods encouraged women to bathe in it to soften their skin. A big thanks to Kathryn McMaster! She’ll give away one paperback copy of Blackmail, Sex and Lies to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Kathryn McMaster! She’ll give away one paperback copy of Blackmail, Sex and Lies to a reader who contributes a comment on my blog. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide. Relevant History welcomes Sharon Bradshaw, a historical fiction author, storyteller, and poet. Sharon loves reading archaeology books and talked to a lot of monks in the 8th century while writing the Durstan series. A Druid’s Magic is set in the real Middle-Earth we called the Dark Ages. Subscribers to

Relevant History welcomes Sharon Bradshaw, a historical fiction author, storyteller, and poet. Sharon loves reading archaeology books and talked to a lot of monks in the 8th century while writing the Durstan series. A Druid’s Magic is set in the real Middle-Earth we called the Dark Ages. Subscribers to  People believed in the existence of elves, faeries, and dragons in a way that was not so far removed from J.R.R Tolkien’s Middle-earth. All of this was reflected in Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art, jewelry, and weapons; ancient place names; and a belief in destiny woven through the threads of the Wyrd. The monks themselves were regarded as spellcasters. The letters they wrote were similar to the marks made by a Druid’s runes.

People believed in the existence of elves, faeries, and dragons in a way that was not so far removed from J.R.R Tolkien’s Middle-earth. All of this was reflected in Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art, jewelry, and weapons; ancient place names; and a belief in destiny woven through the threads of the Wyrd. The monks themselves were regarded as spellcasters. The letters they wrote were similar to the marks made by a Druid’s runes. Many believe that all the Druids were massacred by the Romans during the Boudican revolt c. 60-61AD. Druids in Gaul had been obliterated earlier, and historians relied for centuries on a sparse account by Tacitus (56–120AD) of what happened on the island of Anglesey. He didn’t write from personal experience, and his work is no longer regarded as impartial. Sadly the Druids didn’t leave behind an alternate version of events for us to read. Nor did they use a form of writing which would have enabled them to do so.

Many believe that all the Druids were massacred by the Romans during the Boudican revolt c. 60-61AD. Druids in Gaul had been obliterated earlier, and historians relied for centuries on a sparse account by Tacitus (56–120AD) of what happened on the island of Anglesey. He didn’t write from personal experience, and his work is no longer regarded as impartial. Sadly the Druids didn’t leave behind an alternate version of events for us to read. Nor did they use a form of writing which would have enabled them to do so. A big thanks to Sharon Bradshaw! She’ll give away one ebook copy of A Druid’s Magic to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog as well as one ebook copy to a reader in the United States who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Tuesday at 6 p.m. ET.

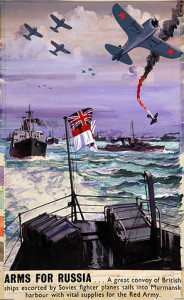

A big thanks to Sharon Bradshaw! She’ll give away one ebook copy of A Druid’s Magic to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog as well as one ebook copy to a reader in the United States who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Tuesday at 6 p.m. ET. Relevant History welcomes Charlotte Milne, a naval daughter who grew up in the Scottish Borders. She worked for the Scottish National Trust, Makerere University in Uganda, and for an American software house. Although writing ‘stories’ since schooldays, she published her first novel, Dolphin Days, in 2017. Come In From the Cold (summer 2019 release), set in Scotland, tells the story of a WW2 naval officer on Russian convoys, through three generations, solving a seventy-year old murder mystery on the way. Charlotte is a keen genealogist and involved in various community-based organisations. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Charlotte Milne, a naval daughter who grew up in the Scottish Borders. She worked for the Scottish National Trust, Makerere University in Uganda, and for an American software house. Although writing ‘stories’ since schooldays, she published her first novel, Dolphin Days, in 2017. Come In From the Cold (summer 2019 release), set in Scotland, tells the story of a WW2 naval officer on Russian convoys, through three generations, solving a seventy-year old murder mystery on the way. Charlotte is a keen genealogist and involved in various community-based organisations. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  In World War 2, Roosevelt and Churchill desperately needed to prevent Russia from allying with Germany. If it did so, they knew the western allies would lose the war. In return for Russia’s alliance with the West, Stalin demanded vast amounts of food and arms for his starving and ill-equipped people. Germany and its allies blocked the land routes, so the only way to get supplies to Russia was by sea. The only ports available were within the Arctic Circle—Murmansk and Archangel—with all of Hitler’s sea and air power under orders to prevent them from reaching Russia.

In World War 2, Roosevelt and Churchill desperately needed to prevent Russia from allying with Germany. If it did so, they knew the western allies would lose the war. In return for Russia’s alliance with the West, Stalin demanded vast amounts of food and arms for his starving and ill-equipped people. Germany and its allies blocked the land routes, so the only way to get supplies to Russia was by sea. The only ports available were within the Arctic Circle—Murmansk and Archangel—with all of Hitler’s sea and air power under orders to prevent them from reaching Russia. Merchant ships gathered in a deep-water anchorage in the west of Scotland called Loch Ewe. Protected by escorts of heavily-armed allied warships, they joined up with other merchant ships in Iceland, and headed, nervously, towards Russia’s only two northern open-water ports.

Merchant ships gathered in a deep-water anchorage in the west of Scotland called Loch Ewe. Protected by escorts of heavily-armed allied warships, they joined up with other merchant ships in Iceland, and headed, nervously, towards Russia’s only two northern open-water ports. Winter storms were indescribable. The winter water temperature often dropped to minus 2 degrees Celsius, air temperature down to minus 22 degrees Celsius, without taking wind into account. Waves were often 40 to 50 feet high, visibility was nil in driving snow and spray, ships came near the vertical both going up and coming down the waves, they crashed and bounced and wallowed and capsized. Capsizing was one of the greatest dangers due to the weight of ice which accumulated above decks from the water flooding the superstructure of ships. Ice accumulated on guns, turrets and shells; masts, rigging, funnels, pipes and guard rails; on containers, aircraft, tanks and munitions stacked on decks, the decks themselves were like ice rinks, doors sealed themselves, ropes, anchors, fenders became as hard as iron and as immoveable. Clothes were inadequate—no ski jackets or cold weather gear as we know it. Crews had to spend hours on deck, tossed about like dolls, chipping at the ice and throwing it overboard, just so that the ship would not turn turtle. Fuel and oil coagulated in the low temperatures. Unimaginable conditions. Unimaginably brave men.

Winter storms were indescribable. The winter water temperature often dropped to minus 2 degrees Celsius, air temperature down to minus 22 degrees Celsius, without taking wind into account. Waves were often 40 to 50 feet high, visibility was nil in driving snow and spray, ships came near the vertical both going up and coming down the waves, they crashed and bounced and wallowed and capsized. Capsizing was one of the greatest dangers due to the weight of ice which accumulated above decks from the water flooding the superstructure of ships. Ice accumulated on guns, turrets and shells; masts, rigging, funnels, pipes and guard rails; on containers, aircraft, tanks and munitions stacked on decks, the decks themselves were like ice rinks, doors sealed themselves, ropes, anchors, fenders became as hard as iron and as immoveable. Clothes were inadequate—no ski jackets or cold weather gear as we know it. Crews had to spend hours on deck, tossed about like dolls, chipping at the ice and throwing it overboard, just so that the ship would not turn turtle. Fuel and oil coagulated in the low temperatures. Unimaginable conditions. Unimaginably brave men. A big thanks to Charlotte Milne! She’ll give away one £5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog this week as well as one $5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the United States or Canada who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET.

A big thanks to Charlotte Milne! She’ll give away one £5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the UK who contributes a comment on my blog this week as well as one $5 Amazon gift card to a reader in the United States or Canada who contributes a comment. I’ll choose the two winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day.

Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day. A big thanks to Renée Dahlia!

A big thanks to Renée Dahlia!