Relevant History welcomes historical mystery author Ashley Gardner, pen name for New York Times and USA Today bestselling author Jennifer Ashley. She has published nearly 40 novels and a dozen novellas since 2002. Her novels have been nominated for numerous awards, including RT BookReviews Reviewer’s Choice award for Best Historical Novel (which she won for The Sudbury School Murders). She has penned seven novels and a novella (thus far) in the Captain Lacey Regency Mystery series. When not writing books, Ashley enjoys cooking, hiking, and building dollhouses and dollhouse miniatures. For more information, check her web site and author blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes historical mystery author Ashley Gardner, pen name for New York Times and USA Today bestselling author Jennifer Ashley. She has published nearly 40 novels and a dozen novellas since 2002. Her novels have been nominated for numerous awards, including RT BookReviews Reviewer’s Choice award for Best Historical Novel (which she won for The Sudbury School Murders). She has penned seven novels and a novella (thus far) in the Captain Lacey Regency Mystery series. When not writing books, Ashley enjoys cooking, hiking, and building dollhouses and dollhouse miniatures. For more information, check her web site and author blog, and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

*****

One reason I enjoy writing historical crime fiction (and indeed, reading it) is that I’m fascinated by crime detection before fingerprinting, DNA tests, police databases, and other modern technology. I’m even more fascinated by the people who did this crime detecting, often very well and with good results.

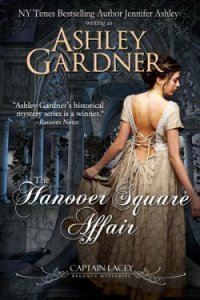

My mystery series (The Captain Lacey Regency mysteries, beginning with The Hanover Square Affair) is set in London in 1816 and beyond. This period predates Robert Peel’s 1829 police reform that established a regular police force.

My mystery series (The Captain Lacey Regency mysteries, beginning with The Hanover Square Affair) is set in London in 1816 and beyond. This period predates Robert Peel’s 1829 police reform that established a regular police force.

In my time period, 1816, several bodies of men worked under different jurisdictions to solve crimes and arrest criminals: The Watch, the Runners, and the Thames River Police. The City of London (the square mile) had its own constables, who didn’t much like interference from those patrolling the rest of metropolitan London

The most famous of the pre-Peel police are the Bow Street Runners. In my series, Captain Lacey’s former sergeant, Milton Pomeroy, becomes one of these elite patrollers, loves getting his convictions, and often calls upon Gabriel Lacey, now a private citizen, to help him out.

A short history of the Bow Street Runners: In 1750, Henry Fielding, magistrate of the Bow Street house (as well as the author of Tom Jones), put in motion a plan to employ six permanent constables at the Bow Street magistrate’s house. Unlike parish constables, who took up constable duties for a year (or paid others to do it for them), “Mr. Fielding’s People” would be more or less permanent employees.

The first Runners (who were not called “Runners” until about 1790) were not paid a salary or stipend; they received rewards for the conviction of criminals. They did not patrol, but investigated crimes that were reported to them.

Sir John Fielding, Henry Fielding’s half-brother, took over the Bow Street office in 1754 and remained there until 1779. Blind since the age of 20, Sir John Fielding took “Mr. Fielding’s People” and built them into an elite, highly respected detective force.

Under Sir John, the Runners were paid a salary in addition to collecting rewards; the magistrates began to receive stipends and sit regular hours. The Bow Street office also began to be used as a clearinghouse for information. Newssheets and journals (including The Hue and Cry or Weekly Pursuit, established by John Fielding in 1772), listed information on wanted criminals and stolen property, and was distributed throughout the country.

A quote from the Weekly Pursuit:

John Godfrey, pretends to be a clergyman, middle-sized, thin visaged, smooth face, ruddy cheeks, his eyes inflamed, a large white wig, bandy-legged, charged with fraud at Chichester.

Bow Street Runners were allowed to pursue criminals or track down missing persons outside of London, something that parish constables or the Watch could not do.

In 1792, the Middlesex Justices Act established seven magistrates houses in addition to Bow Street. Each house had three magistrates and six constables (called Runners in Bow Street, in other houses they might be referred to as Runners, constables, or officers).

The Runners issued warrants for arrest, brought in suspects, and investigated reported crimes. They did not patrol or walk a beat—the Runners only investigated or arrested a suspect once someone (usually the victim or friend/family of the victim), arrived at the magistrate’s office to report a crime.

Runners/constables at the magistrates’ houses were often hired by victims of crimes to hunt down offenders, or to find missing persons. Runners also continued to be given rewards by the magistrates’ office for the conviction of criminals. They were rewarded only when the suspect was convicted of a crime, not simply caught and arrested (although private citizens could pay the Runner for bringing a suspect to the magistrate).

Each magistrate’s house by 1815 employed foot patrollers who assisted the magistrates and the Runners. The foot patrollers actually patrolled in the streets of metropolitan London, while mounted patrollers covered the roads leading to London.

Another branch of crime fighters that greatly interests me is the Thames River Police. In The Glass House (Book 3 of the Captain Lacey Regency Mysteries), I introduce a Thames River Policeman who asks Captain Lacey to help him identify a body pulled out of the river.

The Thames River Police, sometimes called the Marine Police, or simply, the River Police, was sponsored and formed in 1798 by West India merchants and based at Wapping New Stairs. The Marine Police would patrol the Thames River and prevent theft from the merchantmen and docks along the river as well as the warehouses in which goods were stored.

The new police were so successful that, in 1800, the merchant companies (including the East India Company, the West India merchants, United States traders and others), backed a bill to let the government take over the running of the operation. Patrick Colquhoun, a magistrate who had many ideas for police reform, lobbied the government and persuaded them to bring the Thames River Police under their jurisdiction.

The Thames River Police continued to operate throughout the Regency and were incorporated into Robert Peel’s metropolitan police in 1839. (Note that though the metropolitan police began in 1829, the Thames River Police ran under the old system until 1839.)

And the Watch? The much-maligned Watch was created in the late 17th century in London and its boroughs. Unlike the magistrate system, which was set up and regulated by the Home Office, each parish within London was given full control over their Watch. Each parish decided how many men to hire, how much to pay them, how much to supervise them, and what the watchmen would do.

The quality of the Watch in any given part of London depended, of course, on the financial ability of that parish. The Watch system was completely replaced in 1829–30 by the new constables of the Metropolitan Police.

I thoroughly enjoy researching crime-fighting in Regency London—there is much more to it than the little bit I’ve touched on here, but I hope I’ve provided an interesting overview.

*****

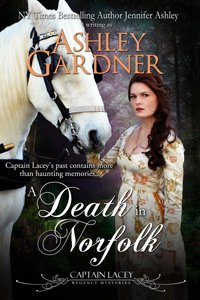

A big thanks to Ashley Gardner. She’ll give away a print or electronic copy of the first Captain Lacey mystery, The Hanover Square Affair (re-released edition) or the newest book, A Death in Norfolk, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Sunday at 6 p.m. ET. International delivery is available.

A big thanks to Ashley Gardner. She’ll give away a print or electronic copy of the first Captain Lacey mystery, The Hanover Square Affair (re-released edition) or the newest book, A Death in Norfolk, to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Sunday at 6 p.m. ET. International delivery is available.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.