Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Chrissie Parker, who writes for the Zakynthos Informer and has written for other publications including The Bristolian, The Huffington Post, Ancient Egypt and The Artist Unleashed. Among the Olive Groves won a Historical Fiction Award in 2016. In 2013 her poem “Maisie” was performed at Bath International Literary Festival’s event “100 poems by 100 women.” Chrissie’s love of history and travel is the inspiration for her books. She has completed two Egyptology courses and an Archaeology course with Exeter University. She is currently working on a follow-up to Among the Olive Groves and a co-authored history book about Zakynthos. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Instagram, and Pinterest.

Relevant History welcomes historical fiction author Chrissie Parker, who writes for the Zakynthos Informer and has written for other publications including The Bristolian, The Huffington Post, Ancient Egypt and The Artist Unleashed. Among the Olive Groves won a Historical Fiction Award in 2016. In 2013 her poem “Maisie” was performed at Bath International Literary Festival’s event “100 poems by 100 women.” Chrissie’s love of history and travel is the inspiration for her books. She has completed two Egyptology courses and an Archaeology course with Exeter University. She is currently working on a follow-up to Among the Olive Groves and a co-authored history book about Zakynthos. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, Instagram, and Pinterest.

*****

When mainland Greece was invaded in 1941 during World War II, life for the Greek population was hard. Initially they were under Italian rule, part of the Axis powers. On 9 September 1943, the small Greek island of Zakynthos, situated in the Ionian Sea, fell under German rule. Despite the hardship of war, Zakynthos would leave Greece with a lasting tale of extreme bravery.

When mainland Greece was invaded in 1941 during World War II, life for the Greek population was hard. Initially they were under Italian rule, part of the Axis powers. On 9 September 1943, the small Greek island of Zakynthos, situated in the Ionian Sea, fell under German rule. Despite the hardship of war, Zakynthos would leave Greece with a lasting tale of extreme bravery.

Terms of occupation

In December 1943 German Commandant Berenz, who was in charge of the German Guards on Zakynthos, met with the mayor of the island, Loukas Karrer. Berenz demanded a full list of Jewish residents living on Zakynthos, with threats of punishment if the request wasn’t granted. Mayor Karrer tried to explain that Zakynthos’s Jewish residents were peaceful people who meant no harm to anyone, but an angry Berenz insisted and threatened Mayor Karrer, telling him that he had seventy-two hours to present a list of all Jewish island residents to him.

Mayor Karrer shared his concerns with the island’s bishop, Chrysostomos, who months before had been a prisoner of the Germans and not long released back to the island. The Bishop visited Berenz who confirmed the request. Berenz also told Chrysostomos that the Jewish population was to be arrested. It’s said that in his shock the Bishop responded that the Jewish residents of Zakynthos were “obedient, good subjects of Greece, who were hard-working and peace loving. They were non-dangerous citizens of Zakynthos who were part of his flock.” The two men argued with weapon and staff drawn and in the end required an intervention by a German Captain, Alfredo Litt. Captain Litt explained to Chrysostomos that they had orders, and the Bishop couldn’t refuse them. After much discussion, Litt and Chrysostomos agreed to meet a few days later to discuss the issue further.

Mayor Karrer shared his concerns with the island’s bishop, Chrysostomos, who months before had been a prisoner of the Germans and not long released back to the island. The Bishop visited Berenz who confirmed the request. Berenz also told Chrysostomos that the Jewish population was to be arrested. It’s said that in his shock the Bishop responded that the Jewish residents of Zakynthos were “obedient, good subjects of Greece, who were hard-working and peace loving. They were non-dangerous citizens of Zakynthos who were part of his flock.” The two men argued with weapon and staff drawn and in the end required an intervention by a German Captain, Alfredo Litt. Captain Litt explained to Chrysostomos that they had orders, and the Bishop couldn’t refuse them. After much discussion, Litt and Chrysostomos agreed to meet a few days later to discuss the issue further.

Creating a plan

The Bishop left and swiftly met with Mayor Karrer, island priests, and rabbis. The group began to plan how to save the island’s Jewish population. Fake documents of religion and citizenship were created and given to all 275 Jews that called Zakynthos their home, and each of them became Christians. Despite this, the seventy-two hours deadline was still in place, and the mayor had to provide a list of Jewish residents to Berenz. Even though they were now “Christians,” the Jewish population was far from safe. Some fearful families left their homes, escaping to the mountains, hiding out where they could. It is rumoured that some even chose island caves as a safe haven.

Bishop Chrysostomos met with Alfredo Litt again and passed him the list reportedly saying, “Here are your Jews”. On the list were two names written both in German and Greek, “Mayor Loukas Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos”. No one really knows why, but for some reason, despite threats of violence from Berenz, Litt assured Chrysostomos that there would be an “exception for the Jews of Zakynthos,” and Litt would speak further with Nazi High Command.

Heading to safety

After days of hearing nothing, Bishop Chrysostomos wrote a personal appeal to Hitler begging that he not arrest the Jews of Zakynthos. Litt retaliated furiously, announcing that every Zakynthian Jew would be rounded up. Full of fear, remaining Jewish families, assisted by the resistance, left their homes and belongings and hid across Zakynthos, ending up in farmhouses, monasteries and cellars.

Shortly after, Litt was seen leaving the island and was swiftly replaced by another German officer. A command was issued to deport all Jews living on Zakynthos. The following day, the Mayor and Bishop explained to the new German officer that there were no Jews on Zakynthos. Their own lives were now threatened. That night Mayor Karrer fled Zakynthos by boat, seeking refuge on another island, and wasn’t seen until after Greece was liberated. Bishop Chrysostomos was lucky to keep his life, and it wasn’t long before the allies liberated Greece.

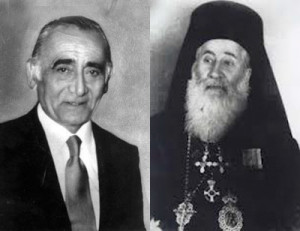

Both courageous men lived through the war and into liberation. It was reported that Alfredo Litt was killed not long after leaving Zakynthos. The entire Jewish population of Zakynthos lived the remainder of the war safely in hiding and went on to normal lives post-war, either moving to Athens or Israel.

A lasting memorial to both Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos stands on the original site of the Zakynthian Jewish Synagogue, destroyed in the Great Ionian Earthquake of 1953. This important memorial marks the incredible heroism of both men, and the story of their bravery lives on in the hearts and minds of the Zakynthian people.

A lasting memorial to both Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos stands on the original site of the Zakynthian Jewish Synagogue, destroyed in the Great Ionian Earthquake of 1953. This important memorial marks the incredible heroism of both men, and the story of their bravery lives on in the hearts and minds of the Zakynthian people.

*****

A big thanks to Chrissie Parker! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Among the Olive Groves to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide, in all electronic versions except PDF.

A big thanks to Chrissie Parker! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Among the Olive Groves to three people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winners from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide, in all electronic versions except PDF.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Relevant History welcomes Nicole Evelina, a historical fiction, non-fiction, and women’s fiction author whose six books have won more than thirty awards, including three Book of the Year designations. The TV/movie option for her book Madame Presidentess was recently acquired by Fortitude International. Her fiction tells the stories of strong women from history and today, with a focus on biographical historical fiction, while her non-fiction focuses on women’s history, especially sharing the stories of unknown or little-known figures. She is currently working on a biography of Virginia Minor. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet.

In Missouri, one such leader was Virginia Minor, who worked closely with her husband, Francis, to fight for women’s rights during her forty-year residency in St. Louis. Her involvement in the suffrage movement came in the uncertain years after the Civil War ended, when women like herself, who had tasted the power of political action and influence in supporting the war effort, faced a return to their traditional domestic lives. This unease, coupled with the tragic death of her only child, meant Virginia needed an outlet. A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about

A big thanks to Nicole Evelina! She’ll give away an electronic copy of Madame Presidentess, historical fiction about  Relevant History welcomes Emma Rose Millar, who writes historical fiction and children’s picture books. She won the Legend category of the Chaucer Awards for Historical Fiction with Five Guns Blazing in 2014. Her novella The Women Friends: Selina, based on the work of Gustav Klimt and co-written with author Miriam Drori, was published in 2016 by Crooked Cat Books and was shortlisted for the Goethe Award for Late Historical Fiction. Her third novel, Delirium, a Victorian ghost story published by Crooked Cat Books, was shortlisted for the Chanticleer Paranormal Book Awards in 2017. Emma’s historical poems for children are published by The Emma Press. To learn more about her and her books, follow her on

Relevant History welcomes Emma Rose Millar, who writes historical fiction and children’s picture books. She won the Legend category of the Chaucer Awards for Historical Fiction with Five Guns Blazing in 2014. Her novella The Women Friends: Selina, based on the work of Gustav Klimt and co-written with author Miriam Drori, was published in 2016 by Crooked Cat Books and was shortlisted for the Goethe Award for Late Historical Fiction. Her third novel, Delirium, a Victorian ghost story published by Crooked Cat Books, was shortlisted for the Chanticleer Paranormal Book Awards in 2017. Emma’s historical poems for children are published by The Emma Press. To learn more about her and her books, follow her on  Worked to the bone, starved, beaten, and abused: this was the fate of some 30,000 women whose care was entrusted to nuns in Ireland’s Magdalene Asylums, also known as Magdalene Laundries. These institutions were set up during the eighteenth-century to house prostitutes—so-called “fallen women”—but quickly became places of unknown cruelty and hardship, where any women and girls as young as nine, branded as “undesirable” by the Church, could be incarcerated. For over two hundred years, unmarried mothers, women deemed “promiscuous,” or those who defied their husbands or fathers could find themselves locked up in one of the asylums. Others had learning difficulties or had been the victims of rape or sexual assault. Some were sent there simply for being “too pretty.” Once there, they were starved, beaten, and forced into backbreaking work in the asylum laundries. Babies were usually taken away from their mothers and offered up for adoption.

Worked to the bone, starved, beaten, and abused: this was the fate of some 30,000 women whose care was entrusted to nuns in Ireland’s Magdalene Asylums, also known as Magdalene Laundries. These institutions were set up during the eighteenth-century to house prostitutes—so-called “fallen women”—but quickly became places of unknown cruelty and hardship, where any women and girls as young as nine, branded as “undesirable” by the Church, could be incarcerated. For over two hundred years, unmarried mothers, women deemed “promiscuous,” or those who defied their husbands or fathers could find themselves locked up in one of the asylums. Others had learning difficulties or had been the victims of rape or sexual assault. Some were sent there simply for being “too pretty.” Once there, they were starved, beaten, and forced into backbreaking work in the asylum laundries. Babies were usually taken away from their mothers and offered up for adoption. It was not until the discovery of a mass grave at Our Lady of Charity Convent in Dublin that the media became involved and printed articles questioning goings-on at the asylums. One hundred and fifty-five bodies were found in the grave, but only seventy-five death certificates had been issued. The nuns claimed there had been an administrative error, but there was a public outcry, and ultimately the United Nations called for a public enquiry. Suddenly, women began perusing cases for violations against Human Rights and making disclosures about the abuse they had suffered.

It was not until the discovery of a mass grave at Our Lady of Charity Convent in Dublin that the media became involved and printed articles questioning goings-on at the asylums. One hundred and fifty-five bodies were found in the grave, but only seventy-five death certificates had been issued. The nuns claimed there had been an administrative error, but there was a public outcry, and ultimately the United Nations called for a public enquiry. Suddenly, women began perusing cases for violations against Human Rights and making disclosures about the abuse they had suffered. A big thanks to Emma Rose Millar! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Delirium to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.K. only.

A big thanks to Emma Rose Millar! She’ll give away a paperback copy of Delirium to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.K. only. Happy New Year! Relevant History welcomes Karen Wills, who lives near Glacier National Park. She writes historical, often frontier, novels. She’s practiced law, representing plaintiffs in Civil Rights cases. She’s taught English classes at college and secondary public school levels, including on South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation and in the Inupiaq village of Wales, Alaska. She’s encountered both grizzly and polar bears and still believes we need wild creatures and wilderness. Her novels include the self-published archaeological thriller Remarkable Silence and traditionally published River with No Bridge. All Too Human will be released in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Happy New Year! Relevant History welcomes Karen Wills, who lives near Glacier National Park. She writes historical, often frontier, novels. She’s practiced law, representing plaintiffs in Civil Rights cases. She’s taught English classes at college and secondary public school levels, including on South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation and in the Inupiaq village of Wales, Alaska. She’s encountered both grizzly and polar bears and still believes we need wild creatures and wilderness. Her novels include the self-published archaeological thriller Remarkable Silence and traditionally published River with No Bridge. All Too Human will be released in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  Fery, born Johann Nepomuck Levy in Strasswatchen, Austria, on 25 March 1859, moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1883, changing his name to John Fery. An outdoorsman, he frequently left his family in Milwaukee to go west to paint. Hill noticed his work and hired him for the “See America First” campaign. Prolific, Fery created big mountainous scenes for the Great Northern that hung in Glacier National Park hotels, Great Northern depots, and ticket agent offices. Fery produced about fourteen huge landscapes per month.

Fery, born Johann Nepomuck Levy in Strasswatchen, Austria, on 25 March 1859, moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1883, changing his name to John Fery. An outdoorsman, he frequently left his family in Milwaukee to go west to paint. Hill noticed his work and hired him for the “See America First” campaign. Prolific, Fery created big mountainous scenes for the Great Northern that hung in Glacier National Park hotels, Great Northern depots, and ticket agent offices. Fery produced about fourteen huge landscapes per month. Julius Seyler was born in Munich, Germany, in 1873. He studied art but also became a competitive ice skater. He achieved fame for both his impressionist art and prowess at speed skating before he came to America.

Julius Seyler was born in Munich, Germany, in 1873. He studied art but also became a competitive ice skater. He achieved fame for both his impressionist art and prowess at speed skating before he came to America. Our third artist, Winold Reiss, was born in Karlsrhuh, Germany, in the Black Forest region, in 1888. He sailed to America in 1913 eager to paint Indians, eventually finding his way to Glacier National Park. While Julius Seyler painted iconic Native American types, Reiss focused in detail on Blackfeet individuals, their features and clothing. His realism appealed to Hill. Reiss’s work, starting in 1933, appeared on calendars and even menus for the Great Northern Railway.

Our third artist, Winold Reiss, was born in Karlsrhuh, Germany, in the Black Forest region, in 1888. He sailed to America in 1913 eager to paint Indians, eventually finding his way to Glacier National Park. While Julius Seyler painted iconic Native American types, Reiss focused in detail on Blackfeet individuals, their features and clothing. His realism appealed to Hill. Reiss’s work, starting in 1933, appeared on calendars and even menus for the Great Northern Railway. A big thanks to Karen Wills! She’ll give away a hardback copy of River with No Bridge to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

A big thanks to Karen Wills! She’ll give away a hardback copy of River with No Bridge to two people who contribute a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.