Note from Suzanne Adair: I became interested in the topic of child soldiers last autumn. While researching an ancestor, Joseph Moseley, who’d fought for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, I was shocked to learn that, contrary to my family’s oral history, Joseph hadn’t joined the army in 1782, at the age of seventeen. He’d joined in 1777, when he was twelve. The outrage I felt resulted in my writing Part 1 and Part 2 of a blog post about the use of child soldiers in history. An editor at Baen Books spotted my blog posts and referred me to science fiction author Mark L. Van Name, who’d just released a novel through Baen that dealt with child soldiers. When I met Mark and heard his personal backstory for the novel, I wanted him as a blog guest. So without further ado…

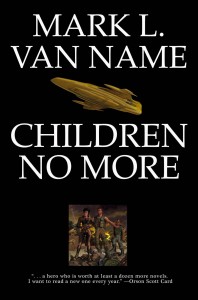

Relevant History welcomes author Mark L. Van Name. Van Name is a writer, technologist, and spoken word performer. He has published four novels (One Jump Ahead, Slanted Jack, Overthrowing Heaven, and Children No More) plus an omnibus of the first two (Jump Gate Twist), and edited or co-edited three anthologies (Intersections, Transhuman, and The Wild Side). His fifth novel, No Going Back, will appear in 2012. He has written many short stories that have appeared in a variety of books and magazines. He has also published over a thousand articles in the computer trade press, as well as a broad assortment of essays and reviews. For more information, visit his web site, or follow his blog.

Relevant History welcomes author Mark L. Van Name. Van Name is a writer, technologist, and spoken word performer. He has published four novels (One Jump Ahead, Slanted Jack, Overthrowing Heaven, and Children No More) plus an omnibus of the first two (Jump Gate Twist), and edited or co-edited three anthologies (Intersections, Transhuman, and The Wild Side). His fifth novel, No Going Back, will appear in 2012. He has written many short stories that have appeared in a variety of books and magazines. He has also published over a thousand articles in the computer trade press, as well as a broad assortment of essays and reviews. For more information, visit his web site, or follow his blog.

*****

When you begin an essay with a title like this one, you’re opening yourself to a lot of challenges. After all, we humans have committed some amazingly terrible acts, from genocide to a pretty thorough trashing of our planet. With all those choices available, picking one is pretty darn tough.

I don’t care. I have my nominee for this dubious distinction, and I’m sticking to it:

Using children as soldiers.

You can make a pretty good case, at least biologically, that the primary imperative of any species, including ours, is to perpetuate the species. Most species take this imperative a step further and protect their young until they are capable enough to protect themselves. It makes sense, after all: it does no good to spawn them if none of them survive. What kind of species instead takes immature children and instead sends them out to fight?

Why us, of course.

And we always have.

In histories of various cultures around the world, you can find mentions time and again of children either serving in war or riding along with soldiers who were heading to war. When David fights Goliath, he is a child.

In some cases, these children were, for their time, basically functioning as adults. They represent a gray area. If a culture is allowing children to marry at twelve, it stands to reason that it would also accord them other adult responsibilities, including the responsibility to fight. I don’t think either is a good plan, and I’d vote against both, but it’s at least understandable that once a boy is receiving the legal treatment of a man, he also has to carry the legal weight of a man.

Far more troubling is the practice of using children as soldiers even when the general culture defines them as children. That’s happened at many points in our history, and it’s still happening today. Best estimates place the number of child soldiers worldwide at over three hundred thousand. Three hundred thousand.

This practice is terrible.

War is brutal on adults. Ask any veteran who’s seen action.

Imagine how hard it is on children. To those who survive, the psychological damage is hard to overstate. Rehabilitating former child soldiers and reintegrating them into society is a terrifically challenging task. It’s time-consuming and expensive, and as with any other kind of rehabilitation, it’s hard work for those undergoing the treatment.

It’s also one I care deeply about. In fact, I care so deeply that it was the topic of my latest novel, Children No More. In that book, I tackle the issue on a faraway planet about five hundred years in the future. Though the story is a fast-paced adventure tale, it’s also one that shows some of the challenges of helping these children.

It’s also one I care deeply about. In fact, I care so deeply that it was the topic of my latest novel, Children No More. In that book, I tackle the issue on a faraway planet about five hundred years in the future. Though the story is a fast-paced adventure tale, it’s also one that shows some of the challenges of helping these children.

I care so deeply about this issue, by the way, that I am donating all the money I make from that book—my advance, ebook royalties, hardback royalties, and paperback royalties—to a charity, Falling Whistles, to help rehabilitate and reintegrate child soldiers and other war-affected children.

I care so much for two key reasons.

One is that this practice is so clearly wrong. Most human cultures throughout history have known it was wrong and not done it, yet still some persist in sending children into combat. We simply must stop doing this.

The other is that I have a personal tie to this practice. Though I was never a child soldier and never fought in war, at the age of ten my mother—with all the best of intentions to get me some male influence and some discipline—enrolled me in a paramilitary youth group. On my first day, the visiting drill instructor, a Marine home on leave from fighting in Viet Nam, screamed at me and belittled me until I cried. As punishment for the tears, he punched me in the stomach. When I fell to my knees and threw up, he ground my face in my own vomit. Later that day, I saw my first—but not my last—human ear collection and learned the rules for collecting ears from fallen opponents. As I’ve written on my blog, that was nowhere near the worst day I endured during the three years I was a member of that group and received extensive training in how to fight and how to kill.

That training happened a long time back, about forty-five years ago now, but it happened right here, in the U.S.

Children are still going to war in many countries.

Just because we’ve done it in the past, we don’t have to do it in the future. We can stop this practice, and we can help those children.

I hope we do.

*****

A big thanks to Mark L. Van Name. He’ll give away a signed first edition of Children No More to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available within the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.