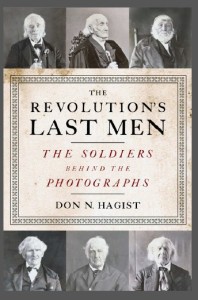

Relevant History welcomes back Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers and has published a number of articles in academic journals. He has written several books including The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs and British Soldiers, American War, both from Westholme Publishing, and is on the editorial board of Journal of the American Revolution. Don works as an engineering consultant in Rhode Island and also writes for several well-known syndicated and freelance cartoonists. For more information, check his Facebook page.

Relevant History welcomes back Don Hagist, an independent researcher specializing in the demographics and material culture of the British Army in the American Revolution. He maintains a blog about British common soldiers and has published a number of articles in academic journals. He has written several books including The Revolution’s Last Men: The Soldiers Behind the Photographs and British Soldiers, American War, both from Westholme Publishing, and is on the editorial board of Journal of the American Revolution. Don works as an engineering consultant in Rhode Island and also writes for several well-known syndicated and freelance cartoonists. For more information, check his Facebook page.

*****

The American Revolution was fought by thousands of soldiers, as most wars are, and as in most wars only a few of the participants achieved fame. As individuals, most soldiers played only minor roles in a long and wide-ranging war, but together their efforts were vital in shaping the course of events. With few exceptions, it was the leaders and policymakers who were remembered, while the soldiers remained almost anonymous.

A quirk of fate changed that for six men who were only teenagers when they served in the war that created their nation. In 1864 an innocuous budget report from the Federal government revealed that only a handful of Revolutionary War veterans were still alive and collecting pensions. When a photographer and a clergyman-activist learned how few of these men remained, the race was on to capture their images and words before the opportunity was lost.

The result of this quest by photographer Nelson Augustus Moore and Reverend Elias Brewster Hillard was the book Last Men of the Revolution. Published at the end of 1864, it contained biographies of the last six Revolutionary War pensioners and, more remarkably, a photograph of each one.

New technology for old veterans

The book was innovative. While daguerreotype photography was already a quarter-century old, the technology to make prints from photographic negatives had been introduced only a few years before 1864. There was still no way to put a photograph onto a printed page, so each copy of Last Men of the Revolution contained individual prints of each man pasted by hand onto the pages. It represented the very latest technology for sharing images, capitalizing on the sensation of photographic image collecting that was sweeping the nation.

The book had great visual appeal, but the biographical content was sorely lacking. Reverend Hillard interviewed five of the six men but did no research to corroborate their garbled tales based on fading memories. Indeed, his goal was not to record history but to inspire the current nation, at the time torn by civil war, with the stories of heroes that had seen first-hand the nation’s founding.

Finding the soldiers behind the photographs

The images captured in 1864 have continued to captivate generations of history enthusiasts ever since. Unfortunately, the error-ridden biographies that were published with those photographs have also been repeated without question, even though much of the information ranges from implausible to impossible. The book has been reprinted verbatim several times, and the images with summaries of the biographies are readily available on the Internet. A new study of these six veterans has been long overdue.

Two years ago, Westholme Publishing asked me if I could research the men profiled in the 1864 book and compose a new volume telling their real stories. It was an interesting proposition; although I’ve researched and written extensively about British soldiers in the American Revolution, that’s a completely different discipline than researching American soldiers. The organization and administration of the army was completely different, and the archival sources used to study it is also completely different. But, unwilling to turn down a book project, I accepted the challenge.

It was quite an adventure. Extensive research revealed a wealth of previously unpublished information about each man and also a new perspective on the 1864 photographs and the 1864 book. It has finally come together in The Revolution’s Last Men: the Soldiers Behind the Photographs (Westholme, March 2015). This new volume presents all of the information that was in the original book but gives it a thorough examination using the pension depositions of the soldiers themselves and men who served alongside them, as well as muster rolls, orderly books, and a host of other primary sources. This is the most complete look at each soldier ever published.

It was quite an adventure. Extensive research revealed a wealth of previously unpublished information about each man and also a new perspective on the 1864 photographs and the 1864 book. It has finally come together in The Revolution’s Last Men: the Soldiers Behind the Photographs (Westholme, March 2015). This new volume presents all of the information that was in the original book but gives it a thorough examination using the pension depositions of the soldiers themselves and men who served alongside them, as well as muster rolls, orderly books, and a host of other primary sources. This is the most complete look at each soldier ever published.

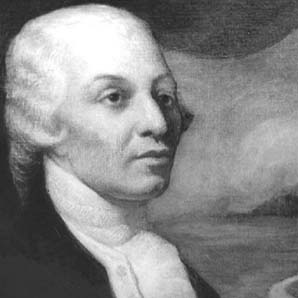

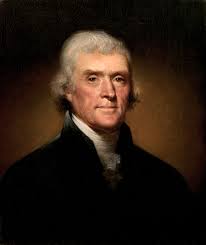

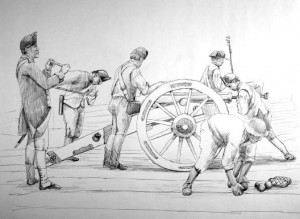

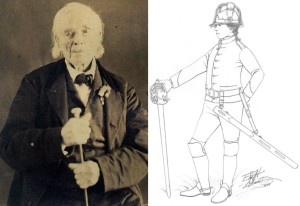

To supplement the textual information, The Revolution’s Last Men includes six original drawings of the men as they may have looked when they were young soldiers, based on extensive study of period military clothing and equipment. Rendered by artist Eric H. Schnitzer, these images put into perspective the photographs taken six decades later, providing new visual context for each man’s military service. [Suzanne Adair’s note: Photograph and sketch are of William Hutchings.]

To supplement the textual information, The Revolution’s Last Men includes six original drawings of the men as they may have looked when they were young soldiers, based on extensive study of period military clothing and equipment. Rendered by artist Eric H. Schnitzer, these images put into perspective the photographs taken six decades later, providing new visual context for each man’s military service. [Suzanne Adair’s note: Photograph and sketch are of William Hutchings.]

The research for The Revolution’s Last Men revealed many unexpected surprises. Besides additional recollections by the veterans not published in 1864, I discovered several photographs taken by other photographers after the men became celebrities due to the publication of the original book. These photographs, along with the drawings and extensive text, make The Revolution’s Last Men a valuable study of memory as well as of history. Creating this book was a remarkably rewarding experience for me, and I hope that you’ll find it enjoyable and informative both to read and to look at.

[Suzanne Adair’s note #2: Don accidentally sent the wrong drawing for William Hutchings. Here is the correct sketch.

[Suzanne Adair’s note #2: Don accidentally sent the wrong drawing for William Hutchings. Here is the correct sketch.

*****

A big thanks to Don Hagist.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter (https://www.subscribepage.com/h8b4e9).