Relevant History welcomes back Jennifer S. Alderson, who was born in San Francisco, raised in Seattle, and currently lives in Amsterdam. Her love of travel, art, and culture inspires her mystery series, the Adventures of Zelda Richardson. Her background in journalism, multimedia development, and art history enriches her novels. In Down and Out in Kathmandu, Zelda gets entangled with a gang of diamond smugglers. The Lover’s Portrait is a suspenseful “whodunit?” about Nazi-looted artwork that transports readers to wartime and present-day Amsterdam. Art, religion, and anthropology collide in Rituals of the Dead, a thrilling artifact mystery set in Papua New Guinea and the Netherlands. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Relevant History welcomes back Jennifer S. Alderson, who was born in San Francisco, raised in Seattle, and currently lives in Amsterdam. Her love of travel, art, and culture inspires her mystery series, the Adventures of Zelda Richardson. Her background in journalism, multimedia development, and art history enriches her novels. In Down and Out in Kathmandu, Zelda gets entangled with a gang of diamond smugglers. The Lover’s Portrait is a suspenseful “whodunit?” about Nazi-looted artwork that transports readers to wartime and present-day Amsterdam. Art, religion, and anthropology collide in Rituals of the Dead, a thrilling artifact mystery set in Papua New Guinea and the Netherlands. For more information about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

*****

Since I finished writing Rituals of the Dead, I have noticed an influx in news reports about the restitution of ethnic artifacts—a topic central to my latest mystery. So we are clear, I am not referring to antiquities such as the Parthenon Marbles (or Elgin Marbles, depending on your nationality). I’m talking about shrunken heads, painted shields, feathered headdresses, carved ancestor sculptures, ritual masks, and the like. The same objects currently filling western museums dedicated to anthropology and ethnography.

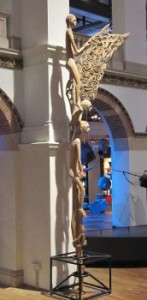

At first, I thought it was a side effect of my research; I was simply noticing these kinds of articles more often. After all, I’d just spent months pouring over accounts of anthropologists, missionaries, and colonial administers who brought Asmat artwork—specifically bis poles—back home from Papua New Guinea and donated or sold them to Dutch ethnographic museums.

At first, I thought it was a side effect of my research; I was simply noticing these kinds of articles more often. After all, I’d just spent months pouring over accounts of anthropologists, missionaries, and colonial administers who brought Asmat artwork—specifically bis poles—back home from Papua New Guinea and donated or sold them to Dutch ethnographic museums.

“African heritage cannot be the prisoner of French museums”

However, I now believe this recent increase in news coverage has everything to do with a promise French President Emmanuel Macron made on 28 November 2017 while in Burkina Faso. He announced the restitution of African artifacts was a priority, stating, “I cannot accept that a large part of the cultural patrimony of several African countries is in France. There are historical explanations for this, but there is no valid, durable, or unconditional justification for it. Africa’s patrimony must be celebrated in Paris but also in Dakar, Lagos, and Cotonou.”

He later reiterated his statement by tweeting, “African heritage cannot be the prisoner of French museums.” Many believe this pledge was in response to Benin’s request for the return of thousands of “colonial treasures” taken at the turn of the century. A French court of law denied Benin’s claim.

Macron’s remarks shine a spotlight on the origins of western ethnographic museum collections and have re-invigorated calls for restitution. Almost all of these cases concern objects collected for western museums from colonized nations in Africa, South America and Oceania between 1900 and 1970.

Exotic representations of “the other”

These artifacts were acquired as representations of the indigenous group’s “otherness.” Anything and everything was shipped back home—ancestor statues (such as bis poles), shrunken heads, decorated skulls, kitchen utensils, weapons, shields, musical instruments, sleeping mats, bowls, and even door frames. The weirder, the better.

These objects were desired by both museums and private collectors. Public displays emphasized the primitive nature of the indigenous groups’ artistic expression or spiritual beliefs. These exhibitions were also a way of asserting western superiority over these regions and peoples, used to justify their colonization and the (often forced) conversion to Christianity of those living within these colonies. In pretty much every case of colonization, the church was there from the beginning, busy converting locals in the belief they were saving their souls, while helping them adjust to western culture, customs, and technological advancements. Papua New Guinea was no exception.

My summary probably seems harsh to you because society has progressed and our attitudes have thankfully changed.

Decolonization and western ethnographic museums

Decolonization in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in a new call for equal rights by indigenous peoples—within their own lands and abroad. It also meant that some of these “exotic” peoples were now immigrating to the colonial motherland. In the Netherlands, their presence dictated a change in the ways these people were represented in the country’s ethnographic museums.

Decolonization in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in a new call for equal rights by indigenous peoples—within their own lands and abroad. It also meant that some of these “exotic” peoples were now immigrating to the colonial motherland. In the Netherlands, their presence dictated a change in the ways these people were represented in the country’s ethnographic museums.

Many of these museums’ showpieces were removed from public displays and hidden away in their depots. New exhibitions were created which focused on geographical and statistical information, as a way of introducing these post-colonial nations to western viewers. They were often neutral displays, heavily dependent on photographs to illustrate aspects of daily life, such as the ways homes were constructed, fields were sown and the types of clothes locals wore.

Only in the last decade or so have these older artifacts been brought back out of storage. However, they are no longer displayed as examples of a people’s “exotic otherness,” but as sublime examples of their cultural and artistic traditions.

Reasserting cultural identity

One of the side effects of the conversion to Christianity was the disappearance of these indigenous groups’ artistic traditions. Sometimes they were voluntarily given up by peoples no longer interested in keeping the “old ways” alive. In other cases, such as Papua New Guinea, their traditions and rituals were banned by Christian missionaries and colonial governments, as part of the pacification process.

Nowadays, the objects collected in the 1900s and displayed in western museums are often the finest examples of an artistic tradition that has died out in its country of origin. Pride of culture has led many recently-formed nations and indigenous groups to try and revive these traditions, as a way of reasserting their cultural identity. Their desire to see these historically-significant artifacts returned has also grown stronger.

An increasing number of countries in Africa, South America and Oceania are submitting claims on these precious examples of their ancestors’ craftsmanship and artistry. So far, the response has been mixed. More often than not, their claims have been denied.

In light of Macron’s promise, how western museums respond to these new restitution claims will be telling. How deeply-seated are feelings of colonial pride in the present generation? And are western museums willing to give up the best pieces in their ethnographic collections and risk becoming obsolete to help these former colonies establish their own cultural institutions?

Author’s note: This is a brief introduction to an extraordinarily complex topic. It is based on research I conducted while working as a collection researcher for the Tropenmuseum, writing my master’s thesis, and my novel Rituals of the Dead.

References to French President Macron’s promise to return African art:

La Monde Afrique

https://hyperallergic.com/414996/emmanuel-macron-restitution-african-art/

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/29/arts/emmanuel-macron-africa.html

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/french-president-promises-restitution-african-heritage-ouagadougou-university-speech-1162199

*****

A big thanks to Jennifer Alderson. She’ll give away either an eARC of Rituals of the Dead (release date 6 April 2018) or an ebook of The Lover’s Portrait—winner’s choice—to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Jennifer Alderson. She’ll give away either an eARC of Rituals of the Dead (release date 6 April 2018) or an ebook of The Lover’s Portrait—winner’s choice—to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.