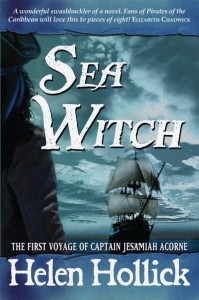

Relevant History welcomes back Helen Hollick, who lives in Devon, England and has been published for many years with her Arthurian Trilogy and the 1066 era. She became a ‘USA Today’ bestseller with her novel about Queen Emma, The Forever Queen (UK: A Hollow Crown.) She also writes the “Sea Witch Voyages,” pirate-based adventures with a touch of fantasy. Her non-fiction book about pirates and smugglers will be published in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, blog, and historical fiction review blog, and follow her on Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes back Helen Hollick, who lives in Devon, England and has been published for many years with her Arthurian Trilogy and the 1066 era. She became a ‘USA Today’ bestseller with her novel about Queen Emma, The Forever Queen (UK: A Hollow Crown.) She also writes the “Sea Witch Voyages,” pirate-based adventures with a touch of fantasy. Her non-fiction book about pirates and smugglers will be published in 2019. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, blog, and historical fiction review blog, and follow her on Twitter.

*****

We see the smugglers of yesteryear portrayed in fiction, movies and TV dramas as small groups of local fisher-folk from picturesque coastal villages intent on making an extra penny to keep their starving families alive. Or we have the nasty ruffian out to bully his vulnerable young nephew into breaking the law by smuggling a keg of brandy, using a somewhat leaky old boat. Images which are true to a point. But only to a point.

We see the smugglers of yesteryear portrayed in fiction, movies and TV dramas as small groups of local fisher-folk from picturesque coastal villages intent on making an extra penny to keep their starving families alive. Or we have the nasty ruffian out to bully his vulnerable young nephew into breaking the law by smuggling a keg of brandy, using a somewhat leaky old boat. Images which are true to a point. But only to a point.

The Trade, the Big Money Makers were far from this romantic view of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century smuggler. The gangs were vicious thugs, organised by efficient leaders who were the Mafia equivalent of their day.

These ‘smuggling companies’ operated along the south-east coasts of England. Not the fictional image of a rugged Cornish cove as in Poldark—the West Country did have its smugglers but they operated in a very different style.

Members of these gangs were not always seamen but landsmen based along the roads leading to London and the larger towns. Seamen brought the cargo in, the gangs collected and dispersed it. If there was trouble from the Revenue Men, the gangs were ready for them. They were comprised of up fifty men, although for larger ‘runs’ this could increase to two or three hundred men if gangs united. The Revenue, by comparison, were ill-informed, undermanned, under-armed and under-paid men. They rarely had any hope of intervening, let alone putting a stop to these formidable opponents, especially when a run had bodyguards wielding stout ash poles for protection. (Think Robin Hood and Little John’s quarterstaff.)

Members of these gangs were not always seamen but landsmen based along the roads leading to London and the larger towns. Seamen brought the cargo in, the gangs collected and dispersed it. If there was trouble from the Revenue Men, the gangs were ready for them. They were comprised of up fifty men, although for larger ‘runs’ this could increase to two or three hundred men if gangs united. The Revenue, by comparison, were ill-informed, undermanned, under-armed and under-paid men. They rarely had any hope of intervening, let alone putting a stop to these formidable opponents, especially when a run had bodyguards wielding stout ash poles for protection. (Think Robin Hood and Little John’s quarterstaff.)

When smuggling began to deplete the purses of the government and the wealthy, something had to be done. By the 1780s the militia and customs men were equipped with better firearms, better ships, and more reliable ‘intelligence,’ which meant they were able to thwart gangs and seize contraband. But the gangs were a tough lot. Well-armed, rough, ruthless men who ensured potential informers kept quiet. Permanently.

The gangs

Several of the gangs had interesting nicknames: ‘Yorkshire George,’ ‘The Miller,’ ‘Old Joll,’ ‘Towzer,’ ‘Flushing Jack’ and ‘Nasty Face.’ These nicknames were used among smugglers and highwaymen not as terms of friendship but to hide a true identity.

The Colonel of Bridport Gang from Dorset were led by ‘The Colonel.’ One contraband cargo was nearly intercepted by the revenue and had to be sunk in the sea to hide it. Alas, it drifted ashore not far from West Bay, to the delight of the locals who claimed the cargo. The Colonel’s gang were successful and never caught. They supplied the Bridport and Lyme Bay taverns with French liquor.

The Groombridge Gang were named for a village west of Tunbridge Wells and were active from about 1730. The Groombridge Gang was first mentioned in a 1733 legal document when thirty men were bringing a cargo of tea inland using fifty horses. Militiamen challenged them but, outnumbered, were disarmed and marched for four hours at gunpoint until the cargo was delivered,, when the militiamen were set free unharmed, but on oath not to renew their interfering. An oath which was not kept!

The North Kent Gang worked from Ramsgate to the River Medway. In 1820 their violent methods increased when blockade-men discovered them bringing in contraband. A fight followed with one officer seriously injured, but the gang got away with the cargo. During the spring of 1821, forty gang members gathered at Herne Bay to land a cargo, protected by twenty men armed with bats and pistols. Unfortunately, these batsmen had enjoyed too much pre-run ‘hospitality’ at a nearby inn. Led by Midshipman Snow, the blockade-men appeared drawn by the noise the drunken smugglers were making. Eighteen smugglers were arrested. Four were hanged, with the others transported to Tasmania.

The two worst gangs

The Northover Gang were from Dorset and named for their leaders. In December 1822 preventative-men, Forward and Tollerway, were on patrol and discovered the smugglers, three of whom dropped the kegs they were carrying and fled. Tollerway guarded the abandoned contraband while Forward seized more kegs after firing his pistol to summon help, but the gang surrounded him. Tollerway ran to give assistance, and fighting broke out. The gang leader, James Northover Junior, was subsequently arrested when assistance arrived and was sentenced to fourteen months in gaol. He served time twice more, and then impressed into the Royal Navy in 1827 for another offence.

The Northover Gang were from Dorset and named for their leaders. In December 1822 preventative-men, Forward and Tollerway, were on patrol and discovered the smugglers, three of whom dropped the kegs they were carrying and fled. Tollerway guarded the abandoned contraband while Forward seized more kegs after firing his pistol to summon help, but the gang surrounded him. Tollerway ran to give assistance, and fighting broke out. The gang leader, James Northover Junior, was subsequently arrested when assistance arrived and was sentenced to fourteen months in gaol. He served time twice more, and then impressed into the Royal Navy in 1827 for another offence.

The Hawkhurst Gang. Hawkhurst is ten miles inland from the Kent and East Sussex coast. Between 1735–1749, the gang became known as the most feared in all England. They smuggled in silk, brandy and tobacco with up to five-hundred men able to assist when required. The gang joined the Wingham Gang in 1746 to bring ashore twelve tons of tea (a lot of tea!) but attacked their partners and made off with the tea and several valuable horses. Despite the benefits of smuggling, villagers grew fed-up with the increasing violence, and a retaliation was made in April 1747. Confident of their influence, the gang marched into the village not expecting to meet an army of people determined to stop the bullying. One of the gang’s hierarchy, George Kingsmill, was shot dead and is buried in Goudhurst churchyard. His brother, Thomas, was hanged at Tyburn in London with his body returned to Kent to rot on the gallows. Does his ghost linger there I wonder?

*****

A big thanks to Helen Hollick!

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.