Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

Welcome to my blog! The week of 2 July – 9 July, I’m participating with more than one hundred other bloggers in the “Freedom to Read” giveaway hop, accessed by clicking on the logo at the left. All blogs listed in this hop offer book-related giveaways, and we’re all linked, so you can easily hop from one giveaway to another. But here on my blog, I’m posting a week of Relevant History essays, each one focused on some facet of the American War of Independence. To find out how to qualify for the giveaways on my blog, read through each day’s Relevant History post below and follow the directions. Then click on the Freedom Hop logo so you can move along to another blog. Enjoy!

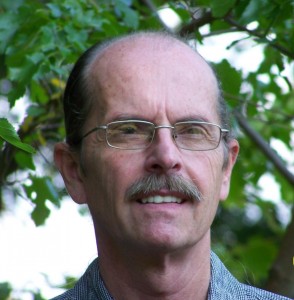

Relevant History welcomes David Neilan, editor of The Francis Marion Papers, targeted for publication in 2015. His essay below is from a longer work: “Francis Marion and Conflicts in Command in the Southern Department.” Other projects include the Hezekiah Maham orderly book, in collaboration with the NY Public Library, and the William Moultrie orderly book. He will be giving a presentation entitled “The Weems-Horry Controversy: Where Fiction Trumped History” at the Francis Marion Symposium in Manning, SC, in October. He may be reached at daveneilan1 (at) gmail (dot) com.

Relevant History welcomes David Neilan, editor of The Francis Marion Papers, targeted for publication in 2015. His essay below is from a longer work: “Francis Marion and Conflicts in Command in the Southern Department.” Other projects include the Hezekiah Maham orderly book, in collaboration with the NY Public Library, and the William Moultrie orderly book. He will be giving a presentation entitled “The Weems-Horry Controversy: Where Fiction Trumped History” at the Francis Marion Symposium in Manning, SC, in October. He may be reached at daveneilan1 (at) gmail (dot) com.

*****

Francis Marion’s activities as a militia leader in South Carolina are the foundation of his legend. The reality of the life of the Swamp Fox is much less romantic. For six months after the fall of Charlestown in May 1780, Marion operated as a guerrilla commander, virtually independent of a formal command structure. It is no wonder that when the Continental Army did rejoin the field, conflicts occurred.

Francis Marion’s activities as a militia leader in South Carolina are the foundation of his legend. The reality of the life of the Swamp Fox is much less romantic. For six months after the fall of Charlestown in May 1780, Marion operated as a guerrilla commander, virtually independent of a formal command structure. It is no wonder that when the Continental Army did rejoin the field, conflicts occurred.

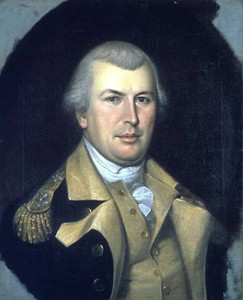

When Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene assumed leadership of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in December 1780, he had only the remnants of an army. Losses at Charlestown and Camden had decimated the ranks. Greene needed the cooperation of the militia to delay the British advance, until a sufficient Continental force arrived to re-take the state. Since authority over the militia rested with State officials, Greene recognized the need for diplomacy to put his plans into effect. His initial “orders” to Francis Marion were couched as requests, using the conciliatory “I beg you” and “Please” to obtain horses and intelligence.

When Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene assumed leadership of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in December 1780, he had only the remnants of an army. Losses at Charlestown and Camden had decimated the ranks. Greene needed the cooperation of the militia to delay the British advance, until a sufficient Continental force arrived to re-take the state. Since authority over the militia rested with State officials, Greene recognized the need for diplomacy to put his plans into effect. His initial “orders” to Francis Marion were couched as requests, using the conciliatory “I beg you” and “Please” to obtain horses and intelligence.

Marion and Greene would clash numerous times during the first half of 1781. Greene’s request for horses would be repeated numerous times. Marion’s response would express his regret, then later his irritation[1]. As the war heated up, so would Greene’s need for horses, but so would the friction between the two over Marion’s failure (Greene’s opinion) or his inability (Marion’s point of view) to supply them.

Greene continued to rely on Marion to take the action to the enemy. In January 1781 Greene dispatched Lt. Col. Henry Lee to join Gen. Marion. In his letter of 16 January, Greene was less conciliatory into his directions: “You [Marion] will give him [Lee] all the aid in your power to carry into execution all such matters as may be agreed on.”

For the next two months, correspondence between Greene and Marion was infrequent. Greene was caught up in racing to the Dan River to avoid the advance of Cornwallis and then fighting the British at Guilford Courthouse. By the middle of April, Greene and the Continental Army were back in South Carolina.

When Lee rejoined Marion, they attacked Fort Watson, a small British fort on the Santee River. During the siege, Marion received stiff criticism from his former commanding officer Gen. William Moultrie. Lee asked Greene to write “a long letr. to Gen. Marion…”[2] Greene outdid himself:

When I consider how much you have done and suffered, and under what disadvantage you have maintained your ground, I am at a loss which to admire most, your courage and fortitude, or your address and management…History affords no instance wherein an officer has kept possession of a Country under so many disadvantages as you have; surrounded on every side with a superior force…To fight the enemy bravely with a prospect of victory is nothing; but to fight with intrepidty under the constant impression of a defeat, and inspire irregular troops to do it, is a talent peculiar to yourself.[3]

Marion did not have long to savor the compliments. Greene again complained to him about his failure to furnish horses.

The 4 May “horse” letter from Greene was the last straw. An exasperated Marion fired back:

I acknowledge that you have repeatedly mention the want of Dragoon horses…if you think it best for the service to Dismount the Malitia…but am sertain we shall never git their service in future. This would not give me any uneasiness as I have sometime Determin to relinquish my command in the militia…& I wish to do it as soon as this post is Either taken or abandoned.[4]

Marion, then in the midst of the siege of Fort Motte with Lee, continued to vent to Greene:

…I assure you I am serious in my intention of relinquishing my Malitia Command…because I found Little is to be done with such men as I have, who Leave me very Often at the very point of Executing a plan…[5]

Fortunately for the American cause, General Greene was in the proximity of Fort Motte. He rode sixty-five miles to meet Marion, arriving shortly after the surrender of the fort 12 May[6].

Although Greene may have mollified Marion during this first meeting, the issues continued. During a brief lull in the fighting, Marion took the opportunity to press for orders to march on Georgetown, South Carolina:

I beg Leave to go & Reduce that place which has not more than 80 British soldiers & a few torys. The Latter is very troublesome…& by the fall of Geor Town will make them quiet.[7]

As long as Georgetown was a safe haven for the enemy, Marion would be unable to maintain his advance over the Santee River.

Marion repeated his plea on 20 May and 22 May without response from Greene. The Swamp Fox delicately announced two days later, “…I find the enemy is about evacuating Georgetown & as I cannot do any thing by remaining here I have thought it most for the service to go to Georgetown…”[8]

Greene deferred ordering an attack on Georgetown, instead advising Marion to obtain permission from Thomas Sumter, who was Marion’s superior officer in the South Carolina militia.[9]

On 28 May Marion liberated Georgetown without firing a shot.

Greene begrudgingly offered his congratulations.[10]

The relationship between Marion and Greene continued to have its ups and downs. Marion’s decisive victory at Parker’s Ferry at the end of August and then his command of the first line of militia and State troops at the Battle of Eutaw Springs in September brought him commendation from Greene.

Despite the occasional conflict over orders, horses, and command issues among subordinates, for the rest of 1781 and throughout 1782 the relationship between Marion and Greene strengthened. By the end of the war, as the two became better acquainted and the war had evolved into a containment operation, Marion was Greene’s most trusted officer.

Despite the occasional conflict over orders, horses, and command issues among subordinates, for the rest of 1781 and throughout 1782 the relationship between Marion and Greene strengthened. By the end of the war, as the two became better acquainted and the war had evolved into a containment operation, Marion was Greene’s most trusted officer.

Footnotes

1. Marion to Greene, 9 Jan 1781, ALS (MiU-C), transcription, Parks, Greene Papers.

2. Lee to Greene, 20 Apr 1781, ALS (MiU-C).

3. Greene to Marion, 24 Apr 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 144-145.

4. Marion to Greene, 6 May 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 214-216.

5. Marion to Greene, 11 May 1781, Greene Papers, 8: 242.

6. Rankin, Swamp Fox, 208.

7. Marion to Greene, 19 May 1781, ALS (MiU-C), transcription, Parks, Greene Papers.

8. Marion to Greene, 24 May 1781, Tr (ScHi, South Carolina Historical Society).

9. Marion to Greene, 24 May 1781, Tr (ScHi), There is a note on the transcript of the letter: On reverse (the outside cover of the letter) that reads, “From Genl. Marion May 24th 1781 (docketed—probably in the hand of Gen. Greene’s ADC.).”

10. Greene to Marion, 10 Jun 1781, Df (NcD).

*****

A big thanks to David Neilan. He’ll give away a DVD of the South Carolina ETV program “Chasing the Swamp Fox” to someone who contributes a legitimate comment on this post today or tomorrow. Delivery is available in the U.S. and Canada. Make sure you include your email address. I’ll choose one winner from among those who comment on this post by Sunday 6 July at 6 p.m. ET, then publish the name of all drawing winners on my blog the week of 14 July. And anyone who comments on this post by the 6 July deadline will also be entered in the drawing to win a copy of one of my five books, the winner’s choice of title and format (trade paperback or ebook).

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.