Historical mystery author Steve Bartholomew reveals a peculiar Victorian precursor to Olympic speed walking.

~~~

Relevant History welcomes back Steve Bartholomew, who grew up in San Francisco but has lived other places such as Mexico City and New York. Now he holes up on the shores of a lake in northern California, away from crowds. He’s been writing since about age nine, published science fiction and some non-fiction, but now is mainly interested in history and historical fiction. He’s always loved history, but only began writing about it when introduced to a sidewheel steamship that sank in 1865, loaded with treasure. The more history Steve looks at, the more treasures he finds. To learn more about him and his books, visit his web site, and follow him on Facebook.

Relevant History welcomes back Steve Bartholomew, who grew up in San Francisco but has lived other places such as Mexico City and New York. Now he holes up on the shores of a lake in northern California, away from crowds. He’s been writing since about age nine, published science fiction and some non-fiction, but now is mainly interested in history and historical fiction. He’s always loved history, but only began writing about it when introduced to a sidewheel steamship that sank in 1865, loaded with treasure. The more history Steve looks at, the more treasures he finds. To learn more about him and his books, visit his web site, and follow him on Facebook.

*****

I write fiction because I like to tell stories. I read about history because I like to read good stories. I don’t mean official history texts, of course. I often dig through old magazines and newspapers. Sometimes I find old neglected books in used book stores, maybe books no one else has read for a hundred years. The Internet has made it possible to scan thousands of newspapers and books published a century ago. Now and then I start looking for something in particular and find something else altogether. That’s how I discovered the walking game.

I was researching streetcars for my latest book, The Driver, set in 1877 San Francisco. It’s a murder mystery; the hero and prime suspect is a streetcar driver. Thus, I was looking through an 1877 issue of the Daily Alta California for information about crime news, robberies, murder, and so on. The Alta is a great source for that sort of thing. My eye was caught by the following clip:

New Advertisements

Pedestrianism Extraordinary!

Miss Kate Lawrence

will walk

100 Miles in 28 hours,

at

Pacific Hall, Bush Street,

Beginning at 8 o'clock on

Tuesday evening August 21,

and ending at midnight on the 22nd.

admission 50 cents

“Pedestrianism extraordinary?” What the heck was that? Admission fifty cents? That would be a high price in 1877, when you could buy a good restaurant meal for a dime.

Naturally, I had to investigate further. My first thought was to wonder if Miss Kate Lawrence was allowed to take bathroom breaks or refreshment during her 28 hours of walking. I don’t know what Pacific Hall was like, but I assume it had some sort of track, either curved or rectangular. Why would anyone want to do this, anyway? And why pay money to watch?

I checked out other papers for various dates and from different cities. Here’s one from the Sacramento Union, 1879:

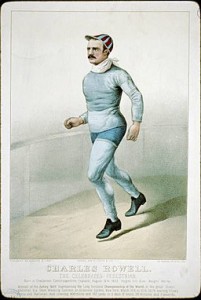

Weston has succeeded in walking 550 miles, and has won a bet and a belt, and the questionable honor of having the particulars of his feat telegraphed all over the world. The passion for pedestrianism which this affair illustrates is neither more nor less respectable than any other of the popular fancies which succeed one another in an interminable procession. The fact that Weston has walked so many miles is an utterly useless fact. It has no bearing upon anything which can improve the condition of the human race. As an amusement pedestrianism is of the mildest. We do not believe that these spasms of athleticism produce any permanent good in the world, even in encouraging bodily exercise...

Newspapers in those days often drew a thin line between reporting and editorial. This fellow named Weston was apparently a leading athlete in his sport, which the above writer found to be “utterly useless.”

Some athletes achieved the feat of walking a thousand miles without stopping. I wonder what brand of shoes they were wearing? A wonderful opportunity for product placement. But of course no one had yet thought of that.

“Pedestrianism” was a real thing in the 19th century. There were efforts to revive the sport (if you can call it that) as late as the 1920’s. Apparently it was replaced by something called race walking, or speed walking, which became an Olympic event. So those of us in these modern times are deprived of the opportunity of paying fifty cents to watch a lady walk around in circles for 28 hours.

Of course, there were a lot of other things going on in San Francisco in 1877. It was the year of the city’s worst race riot, when a few malcontents tried to burn down Chinatown. There were murders and bank robberies. Black Bart was robbing Wells Fargo stagecoaches. There were bank failures and threats of war. Watching a lady walk around in circles might have seemed like a nice way to get away from it all. It could have been almost as exciting as watching paint dry. Maybe we should consider bringing back the walking game.

*****

A big thanks to Steve Bartholomew!

A big thanks to Steve Bartholomew!

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her

Renée Dahlia is an unabashed romance reader who loves feisty women and strong, clever men. Her books reflect this, with a side-note of dark humour. Renée has a science degree in physics. When not distracted by the characters fighting for attention in her brain, she works in the horse racing industry doing data analysis and writing magazine articles. When she isn’t reading or writing, Renée wrangles a partner, four children, and volunteers on the local cricket club committee as well as for Romance Writers Australia. To learn more about her and her books, visit her  Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day.

Enter “Mr Martin.” He agreed to cover the event for The Sportsman for the fee of one guinea, with full results wired at the end of the meeting. As this day was one of the few public holidays in 1898, it was a huge day for the races, and very busy with bookies. The bookies did a roaring trade on Trodmore, bigger than expected for a minor meeting but not completely unexpected for a holiday. The evening papers published the results from the major meetings held that day but didn’t publish the Trodmore results until the next day. A big thanks to Renée Dahlia!

A big thanks to Renée Dahlia!