Relevant History welcomes back Mary Reed aka Eric Reed, pseudonym for Mary Reed and Eric Mayer, co-authors of the John, Lord Chamberlain, mystery series set in 6th century Byzantium. Murder in Megara, the eleventh entry, was published in October 2015 by Poisoned Pen Press. The Guardian Stones, a World War Two mystery set in rural Shropshire, England, appeared in January 2016 from the same publisher. To learn more about them and their books, visit their web site and blog, and follow them on Twitter (Mary and Eric.)

*****

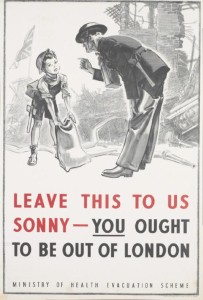

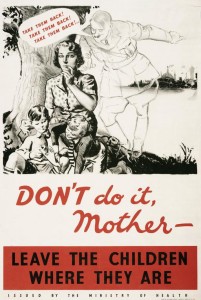

This past month or two the news has been full of reports of evacuations from wild fires or floods, but they pale by comparison to the voluntary evacuation of about twenty percent of British children on the very eve of World War Two. Other evacuations occurred later, but this was the first event of its kind and the largest mass movement of civilians carried out in the UK.

Planning for the event had begun in May 1938 as it became increasingly obvious the outbreak of hostilities was inevitable. Hansard, the official record of the proceedings in Parliament, reported work on the task in hand 2 February 1939. During a House of Commons debate on air raid precautions, in response to a question from the MP representing a Tyneside town, the Lord Privy Seal stated plans were then in preparation for evacuating Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gateshead schoolchildren.

Planning for the event had begun in May 1938 as it became increasingly obvious the outbreak of hostilities was inevitable. Hansard, the official record of the proceedings in Parliament, reported work on the task in hand 2 February 1939. During a House of Commons debate on air raid precautions, in response to a question from the MP representing a Tyneside town, the Lord Privy Seal stated plans were then in preparation for evacuating Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gateshead schoolchildren.

Newcastle-on-Tyne being my (Mary) birth city, naturally I was interested how the situation was handled there, and details will serve as an example of arrangements put in hand all over the country.

Dress rehearsals

Staggering logistical problems faced those organising the nation-wide evacuation of children as part of the unfortunately-named Operation Pied Piper.

Just how complex these plans were can be gleaned by perusing “Evacuation of Civilian Population from Newcastle and Gateshead In The Event of Emergency.” The document was sent in mid-August 1939 to local authorities in Newcastle-on-Tyne and Gateshead by the London & North-East Railway, which was to carry out evacuation over the course of two days.

Schoolchildren accompanied by their teachers and helper-volunteers were to leave on the first day, with passengers on the second composed of what were termed special classes, these being predominantly mothers with children too young to attend school. Payment for evacuating trains was agreed between the railway and the Ministry of Transport.

To familiarise all concerned with what they should do and where they should go when the day arrived, a dress rehearsal was held in late August 1939 in the two cities.

The LNER booklet includes a chilling note that “Should hostilities begin before evacuation is completed the pre-arranged plan may require to be modified”. In the event, changes were not necessary but it was a close-run thing. The official order for evacuation to begin was issued in the late morning of 31 August 1939, and the first two days of September saw the removal of children from the two cities to rural areas of Westmoreland, Cumberland, Yorkshire, and Northumberland.

Only just in time: war was declared on 3 September 1939.

Even a glance at the LNER booklet provides a hint of the massive planning and coordination effort between local authority officials, schools, the police, railway personnel, and others needed to get children at risk away from Tyneside.

o District Evacuation Officers were made responsible for arrangements for the evacuation of schools in their specific districts. They were also to serve as liaison between individual railway stations and the schools being evacuated therefrom.

o Coloured armlets would identify the roles of those wearing them. Thus Newcastle-on-Tyne Evacuation Officers would wear blue armlets, and teachers white ones.

o All passengers were to be labeled or ticketed as proof they were permitted to travel on the evacuating trains.

o The railway’s Liaison Officers would have sole charge of entraining and would work with the Evacuation Officers when the official order to evacuate had been issued.

o Medical personnel were to be available at each station in case children become distressed.

o The public and mothers of the children evacuated on the first day were not to be allowed on the platforms during evacuation.

There must have been many tears at parting and in the temporary homes to which evacuees were sent. Their experiences were varied to say the least. Some met nothing but kindness, others were ill-treated, sometimes physically abused. Some who were homesick or unhappy at being sent away from their families absconded in an attempt to rejoin them, though others were reportedly relieved to be living away from their old homes due to bad conditions or neglect there. Indeed, a number of children arrived with less than the minimum of recommended luggage. Not every family could afford to send their children off with spare clothing, a warm coat, or even such basic necessities as a toothbrush and handkerchiefs.

Not all children were sent away

Many parents kept their children at home because they did not want to be separated from them. Another factor in their decision was the difficulty and expense of the travel needed for them to visit their evacuated children. Some evacuees were brought back when they fell ill or had accidents and older children who had contributed to the family income returned as they were still needed to do so.

Many parents kept their children at home because they did not want to be separated from them. Another factor in their decision was the difficulty and expense of the travel needed for them to visit their evacuated children. Some evacuees were brought back when they fell ill or had accidents and older children who had contributed to the family income returned as they were still needed to do so.

In response to a question put to the Minister of Health on 1 February 1940 concerning how many unaccompanied children had returned to certain cities, the Minister reported a January estimate had noted that of 28,300 children evacuated from Newcastle-on-Tyne, 14,000 were already back in the city. There does not seem to be any comparable figure readily available for Gateshead, from which 10,598 children had been sent away, but in both cities 71 percent of eligible schoolchildren were evacuated.

Birmingham, another major industrial city, sent over 25,000 schoolchildren to safer areas. In The Guardian Stones, published as by Eric Reed, we introduced a handful of trouble-making evacuee children from Birmingham whose behaviour made them not particularly welcomed by the residents of Noddweir, a remote Shropshire village near the Welsh border. The second book in the series is now being written and will take Grace Baxter, one of the main characters in The Guardian Stones, to wartime Newcastle-on-Tyne.

*****

A big thanks to Eric Reed. They’ll give away an ebook copy of The Guardian Stones to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

A big thanks to Eric Reed. They’ll give away an ebook copy of The Guardian Stones to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available worldwide.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.

Relevant History welcomes M. Ruth Myers, who received a Shamus Award from the Private Eye Writers of America for Don’t Dare a Dame, the third book in her Maggie Sullivan mystery series. The series follows a woman private investigator in Dayton, Ohio, from the end of the Great Depression through the end of WW2. Other novels by the author, in various genres, have been translated, optioned for film, and condensed for magazine publication. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri J-School and worked on daily papers in Wyoming, Michigan and Ohio. To learn more about Ruth and her books, visit her

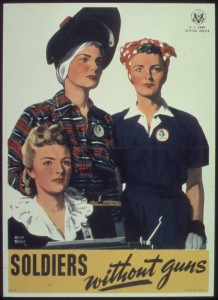

Relevant History welcomes M. Ruth Myers, who received a Shamus Award from the Private Eye Writers of America for Don’t Dare a Dame, the third book in her Maggie Sullivan mystery series. The series follows a woman private investigator in Dayton, Ohio, from the end of the Great Depression through the end of WW2. Other novels by the author, in various genres, have been translated, optioned for film, and condensed for magazine publication. She earned a Bachelor of Journalism degree from the University of Missouri J-School and worked on daily papers in Wyoming, Michigan and Ohio. To learn more about Ruth and her books, visit her Housing was just one of the hardships faced by women whose husbands flooded into the military. If they wanted to live with their husband while he was in training, they’d find themselves sharing an apartment with another couple, or living in a lean-to, possibly with no bathtub. Nor were they always welcomed by locals. Two teachers from Missouri recall being called “low-down soldiers’ wives” and “damn Yankees” when they went to see their husbands at Ft. Knox, KY. The “rooms” they managed to find consisted of cots in the hall of rooming houses. When their husbands shipped out, women knew they wouldn’t see them again until the war ended—or they came home too badly wounded for further service. Because the military censored letters from men in uniform, the women at home didn’t even know the country where they were stationed.

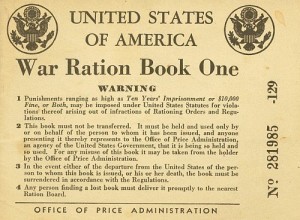

Housing was just one of the hardships faced by women whose husbands flooded into the military. If they wanted to live with their husband while he was in training, they’d find themselves sharing an apartment with another couple, or living in a lean-to, possibly with no bathtub. Nor were they always welcomed by locals. Two teachers from Missouri recall being called “low-down soldiers’ wives” and “damn Yankees” when they went to see their husbands at Ft. Knox, KY. The “rooms” they managed to find consisted of cots in the hall of rooming houses. When their husbands shipped out, women knew they wouldn’t see them again until the war ended—or they came home too badly wounded for further service. Because the military censored letters from men in uniform, the women at home didn’t even know the country where they were stationed. A big thanks to M. Ruth Myers. No Game for a Dame (Maggie Sullivan #1) is available free for

A big thanks to M. Ruth Myers. No Game for a Dame (Maggie Sullivan #1) is available free for