Relevant History welcomes Barbara Ridley, who was born in England but has lived in California for over 35 years. After a successful career as a nurse practitioner, which included publication of academic articles in peer-reviewed journals, she is now focused on creative writing. Her debut novel, When It’s Over, (She Writes Press, 2017), set in Europe during WWII, was a finalist in six awards, including the 2018 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, the Next Generation Indie Book Awards, and the American Fiction Award. Her work has also appeared in Writers Workshop Review, Ars Medica, The Copperfield Review, Blood and Thunder and Stoneboat, among other places. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Relevant History welcomes Barbara Ridley, who was born in England but has lived in California for over 35 years. After a successful career as a nurse practitioner, which included publication of academic articles in peer-reviewed journals, she is now focused on creative writing. Her debut novel, When It’s Over, (She Writes Press, 2017), set in Europe during WWII, was a finalist in six awards, including the 2018 IBPA Benjamin Franklin Awards, the Next Generation Indie Book Awards, and the American Fiction Award. Her work has also appeared in Writers Workshop Review, Ars Medica, The Copperfield Review, Blood and Thunder and Stoneboat, among other places. To learn more about her and her books, visit her web site, and follow her on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

*****

My novel When It’s Over is based on my mother’s story; she was a refugee from the Holocaust during WWII. After her death, I got the idea of writing something to preserve the memory of her experience but quickly realized there were too many gaps in my knowledge to write it as memoir. So I decided to write a novel, which gave me the freedom to make up whatever I didn’t know.

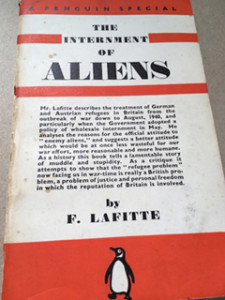

But I wanted it to be historically accurate, so I did a ton of research. Early in that process, I came upon a book on my parents’ bookshelves—this was after they had both died, but before we had cleared out the house and their hundreds of books. It was a small 1940’s style Penguin paperback called The Internment of Aliens by F. Lafitte. I was astonished to learn that thousands of Germans, Austrians, and Italians were interned in England in 1940, as “enemy aliens.”

But I wanted it to be historically accurate, so I did a ton of research. Early in that process, I came upon a book on my parents’ bookshelves—this was after they had both died, but before we had cleared out the house and their hundreds of books. It was a small 1940’s style Penguin paperback called The Internment of Aliens by F. Lafitte. I was astonished to learn that thousands of Germans, Austrians, and Italians were interned in England in 1940, as “enemy aliens.”

Having lived in California for 35+ years, I was familiar with the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, but I had no idea a similar large-scale internment took place in England. This occurred after the fall of France and the other nations of Western Europe, when the threat of imminent German invasion was real. But the practice of internment was very controversial, and Lafitte’s book, written at the time, was a polemical critique of the policy. Arrests were indiscriminate; confirmed Nazi sympathizers were interned along with Jews or Communists who had fled for their lives and reached Britain as refugees. Most of the internees were detained in camps for the duration of the war, or shipped overseas to Canada or Australia. In one tragic, wartime twist of fate, hundreds perished when their ship, the Arandora Star, was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland by a German U-boat in July 1940.

My novel opens with a scene in which the protagonist, Lena, a young Czech Jewish woman (who is based on my mother), is trapped in Paris just before the Nazis overran France, unable to obtain an entry visa for Britain. Some readers have expressed surprise that she had that difficulty. I guess it’s because in hindsight, we know that people needed to flee, and that terrible things happened to those who stayed behind. My mother and all her friends had family members who eventually perished in Nazi gas chambers. So there seems to be an assumption that all good people reached out to help Jewish refugees.

But my mother and her friends did not find it easy to reach safety. They escaped in different ways, mostly illegal, or through clever manipulation of legal methods. They smuggled across borders, fabricated stories, forged domestic worker sponsorships, overstayed visitor visas. Once they reached England, they were not always easily accepted; they faced suspicion and animosity towards foreigners, or internment—when they had the most to lose in the event of a Nazi invasion.

The United States

The response from other nations was not much better. In July 1938 at the Evian Conference, delegates from 32 nations, including the United States, expressed sympathy for the Jews in Germany and Austria but made one excuse after another for not taking any refugees, in spite of calls to “act promptly.” In the United States, a 1939 Gallup poll revealed 83% of Americans were opposed to the admission of more Jewish refugees. A bill to admit 20,000 German Jewish children into the U.S. failed, with the argument: “Ugly children will soon grow up to be ugly adults.”

And then there was the tragic tale of the ship the St. Louis. In May 1939, 900 Jews left Germany for Cuba with the understanding that they would ultimately be admitted to the United States. In Cuba, only 29 were allowed to disembark. The ship then spent 35 days off the Eastern U.S. coast waiting to be accepted, before giving up and returning to Europe. Most of those on board perished in the Holocaust.

And then there was the tragic tale of the ship the St. Louis. In May 1939, 900 Jews left Germany for Cuba with the understanding that they would ultimately be admitted to the United States. In Cuba, only 29 were allowed to disembark. The ship then spent 35 days off the Eastern U.S. coast waiting to be accepted, before giving up and returning to Europe. Most of those on board perished in the Holocaust.

The lessons for today

Today, Europe is experiencing the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War, and we have all seen images of children drowned on a beach or sitting shell-shocked in an ambulance. Desperate people are fleeing wars or persecution in Syria, Eritrea, and Afghanistan. Closer to home in the U.S., thousands are fleeing unimaginable violence in Central America—the area with the highest murder rate in the world—and risking the dangerous journey to cross into the United States. And climate change, with its extremes of drought and floods, threatens the livelihood of millions of people throughout the developed world. This is projected to unleash further waves of migration over the coming decade.

Perhaps today’s conflicts seem complex, with no easy solutions. The numbers of people seeking refuge seem overwhelming, and perhaps the antagonism and fears exploited by populist politicians seem understandable on some level. But the situation today is not that different from the 1930’s. Desperate people will always look for ways to flee to safer ground. Higher walls and militarized borders will not stop them. The only reason a mother puts her child in a rickety boat, or hands him to a “coyote” heading for the desert, is if it seems safer than staying put.

The answer is not to harden our hearts and put up barriers. We have a moral obligation to help and support refugees. And to put our resources into addressing the underlying problems: aggressive diplomatic efforts to stop ethnic cleansing, end military support for dictatorships, and a robust “Marshall-type” plan to combat global inequality and climate change, to make the world safe for everyone.

*****

A big thanks to Barbara Ridley. She’ll give away a paperback copy of When It’s Over to someone who contributes a comment on my blog this week. I’ll choose the winner from among those who comment by Friday at 6 p.m. ET. Delivery is available in the U.S. only.

**********

Did you like what you read? Learn about downloads, discounts, and special offers from Relevant History authors and Suzanne Adair. Subscribe to Suzanne’s free newsletter.